Dune erosion

Definition of Dune erosion:

Sand loss from a dune under wave attack, mainly by notching, avalanching and slumping processes.

This is the common definition for Dune erosion, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

This article deals with dune erosion by storms and provides some simple rules from which retreat of the dune front can be estimated. The focus is on the so-called 'collision regime', where waves hit the dune without exceeding the dune crest.

Contents

Introduction

Coastal dunes have developed naturally along many shorelines worldwide during the last millennia when sea-level rise slowed down. Wave action and onshore winds are the main agents for coastal dune development and sufficient sand supply to the coast is a primary condition[1], see also the article Dune development. The coastal dune belt in many cases protects low-lying hinterland from flooding by the sea. Dune erosion therefore can be a serious threat.

A coastal dune can suffer large losses when attacked by storm waves. The front dune can be taken away over several tens of meters, leaving a steep dune scarp, see Fig. 1. For the Dutch coast it has been estimated that under exceptional circumstances (extreme storms of very long duration, which may occur with a yearly probability of 1/100,000) the dune volume loss can amount to 800 m3/m, causing the dune foot to recede from 80-100 m at some places[2].

The actual dune loss depends on many factors[3]:

- beach geometry (pre-storm): beach slope and width;

- grain size;

- dune geometry (pre-storm): dune face slope, dune crest elevation;

- nearshore morphology: nearshore slope, rip-channel embayments, nearshore sandbars, subtidal morphology;

- beach and dune vegetation; presence of (embryo-)foredunes;

- presence of hard engineered structures;

- alongshore variability in wave energy and dune height.

The dune toe elevation (beach width[math]\times[/math]slope) appears to be a major factor; observations show that vulnerability to erosion decreases with increasing dune toe elevation[4]. Dune sand losses have also been positively correlated with the steepness of the dune face[5]. There is instead strong evidence that dunes are less impacted by storms when situated on dissipative flat beaches than on reflective steep beaches[6].

Dune loss also depends on storm characteristics: maximum sustained wind speed and duration; maximum water level and simultaneous wave height, period and incidence angle.

If at least part of the dune belt survives the storm, it can recover by natural processes – similar to the processes that created the original dune. See section Post-storm dune recovery. Because recovery of the beach-dune profile (especially the dune profile) takes much longer than storm erosion, the dune system is particularly vulnerable to storm clusters (quick succession of storms)[7]. The probability that extreme dune recession is caused by a storm cluster is greater than the probability that this retreat is caused by an individual storm[8].

Figure 2 shows as an example a model result of the relationship between dune foot retreat [math]RD[/math] (expressed as the distance between pre-storm and post-storm dune foot locations) and exceedance frequency (the probability that in a particular year a storm occurs that produces greater erosion) for a location along the Dutch coast. According to this figure, which is based on the storm profile method, there is a 10-5 probability per year that dune erosion will exceed 85 m.

To establish such a relationship, knowledge is required of extreme storm conditions with a very low probability. For these storms, the joint probability of extreme surge height, surge duration and corresponding wave conditions has to be determined[9]. Dune retreat estimates with an exceedance probability of 10-5 are subject to great uncertainty, as reliable measurements of extreme water levels and wave conditions are only available over relatively short periods of the order of 100 years. This issue is further discussed in section Dune failure probability.

Impact of dune erosion

Buildings on the front dune situated close to the dune foot are at risk under severe storms, see Fig. 3. A sound estimate of potential dune erosion is required when issuing building permits (see Setback area). In cases where the hinterland is situated below sea level, the dune belt serves as sea defence. Breach of the dune belt may have catastrophic consequences. Dune and beach monitoring and dune management are of crucial importance. In some cases, where the dune belt consists of a single dune row, dune reinforcement or shore nourishment may be needed. An example is the so-called 'Sand Engine' on the Dutch coast[10], which contributed to the reinforcement of the single protecting dune row through wind-driven sand transport from the widened beach[11].

To ensure safety, several methods have been developed for estimating dune loss during exceptional storm conditions.

Brief explanation of dune erosion processes

The initial cross-shore beach profile, considered to be in a more or less dynamic equilibrium condition with normally occurring hydrodynamic conditions, will be reshaped during a severe storm surge. Offshore directed sediment transport will occur, including sand eroded from the dune.

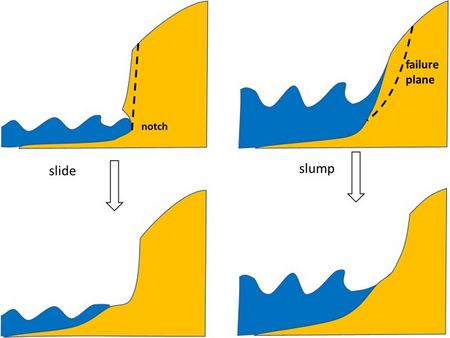

A dune front attacked by storm waves is usually scarped by slumping or sliding processes (Figs. 4, 5). Dune scarping can occur over the entire dune face, but for high dunes, the height of the dune scarp will generally not reach the dune crest[5].

Slumping occurs if the pore pressure along a plane inside the dune exceeds the intergranular stress of the soil matrix. [12] This may occur when the groundwater level inside the dune oscillates as a result of repeated wave uprush and downrush. The zone above the groundwater table consists of a capillary fringe and an unsaturated (moist) zone where the pore pressure is negative due to suction forces (see Beach groundwater). This negative pore pressure confers stability to the sand body. However, when this zone becomes saturated by infiltrating seawater during wave uprush, the stabilizing suction force vanishes. The loss of soil stability is then compensated for by the pressure of the uprushing seawater. In the subsequent downrush phase, this stabilizing external water pressure disappears. As the groundwater level inside the dune does not instantaneously follow the drop in the external water level, the pore pressure exerted by the raised groundwater table is no longer counteracted by suction forces. It may then occur that the pore water pressure along a concave plane inside the dune exceeds the intergranular stress. This will cause the sand body above to slump down along this shear failure plane. The size and frequency of slumps depend not only on wave uprush and downrush characteristics, but also on geotechnical soil properties, such as the adaptation of the soil skeleton to fluctuations in the external stress (increase during wave uprush and decrease during wave downrush)[13]. For further explanations on soil mechanics, see Wave-induced soil liquefaction.

Sliding is another common mode of dune erosion. It occurs when the dune slope is undermined by waves colliding at the toe of the dune. If the groundwater level does not exceed the dune toe, a notch will be formed. The overhanging sand body will slide down when its weight exceeds the stabilizing frictional and suction forces.[14]

The angles of the critical failure plane with the vertical axis correspond in both cases to the Mohr-Coulomb criterium [math]\, \tau_f = c + \sigma' \, \tan \phi \;[/math], where [math]\tau_f[/math] is the shear stress on the failure plane, [math]c[/math] the cohesion (friction+suction forces), [math]\sigma'[/math] the normal effective stress on the failure plane and [math]\phi[/math] the friction angle. [15]

Fig. 4. Dune scarp mechanisms. Field experiments suggest that slumping and sliding are the dominant processes driving dune erosion[16]. |

A slab that slides down the dune scarp will temporarily defend the dune face, until waves and currents mobilize the sediment from the slump deposit and transport it offshore. After the sediment is transported away, the dune face is left exposed again, leaving room for a new sliding or slumping event. The total impact of a storm on the dune strongly depends on how fast the sand deposit at the toe is transported offshore during the storm[16].

Part of the sand eroded from the dune face is removed further down by the backwash and the seaward undercurrent ('undertow') under the breaking waves. Turbulence generated by wave bores is an important driver of offshore suspended sediment transport in the surf zone[17]. Most of the sand is deposited on the lower beach or upper shoreface. In cases where strong rip currents are present or a strong ebb current from nearby inlets, part of the sand can even be transported to the lower shoreface[6].

Sand accumulated at the dune toe decreases the rate of dune erosion with time during the storm surge. The slope of the cross-shore profile then gradually decreases. Usually, the limited storm surge duration does not allow for the development of a new equilibrium profile. The shape of the cross-shore profile after the storm surge, which is a transient state between the initial profile and the storm equilibrium profile, is often called 'storm erosion profile'.

Quantification of dune erosion

Although 3D effects are generally important in the dune erosion process, often a 1D or 2DV approach is adopted, ignoring alongshore variability. In this case the dune erosion process is considered as a typically offshore directed cross-shore sediment transport problem. Sand from the dunes is transported to deeper water and settles there.

A first approach consists of assuming a closed sediment balance in cross-shore direction. The same volume of sand which is eroded from the dunes and the very upper part of a cross-shore profile is accumulated lower in the cross-shore profile. [Because of differences in porosity of the eroded dune material (often loosely packed) and the settled material (often a bit more densely packed), the volume balance is not always strictly closed.]

During severe storm surges with greatly increased water levels (a water level increase of a few meters is possible along some coasts), huge volumes of sand from the dunes are transported in offshore direction, on the order of hundred or several hundred meters3/m [5].

Storm profile method

A quick first order estimate of storm dune erosion can be obtained by assuming that the storm erosion profile is close to the storm equilibrium profile. This assumption is unrealistic for storms of short duration and strongly overestimates storm dune erosion in this case. However, for storms of very long duration, which produce great dune losses with low exceedance probability, the assumption of a post-storm equilibrium profile is not unreasonable. The method is still used in the Netherlands, besides other more advanced methods, to provide an upper bound of possible storm dune erosion[18]. It is based on empirical post-storm equilibrium profiles established by laboratory experiments and validated by field data of the Dutch coast [19]. The post-storm equilibrium profile was established for different values of the significant wave height [math]H[/math], peak wave period [math]T[/math] and mean fall velocity of dune sand [math]w[/math]. Major assumption are:

- the storm duration is sufficient for establishment of a post-storm equilibrium profile [math]y(x)[/math];

- the post-storm equilibrium profile does not (strongly) depend on the initial coastal profile [math]y_0(x)[/math];

- eroded dune sediment is deposited within a zone delimited by a storm closure depth [math]y_{max}[/math];

- the eroded dune scarp has a slope 1:1 and the slope at the toe of the sand deposit is 1:12 (these are less crucial assumptions).

With these assumptions the eroded dune volume is given by the beach volume between [math]y(x)[/math] and [math]y_0(x)[/math], such that the total sand volume landward of the storm closure depth [math]y_{max}[/math] is preserved. The procedure is explained in Fig. 6, where the empirical parameterized functions for the post-storm equilibrium profile [math]y(x)[/math] and the storm closure depth [math]y_{max}[/math] are also indicated. The cross-shore distance over which sand is redistributed (the storm active zone) is given by [math]x_{max}[/math].

The empirical formulas representing the post-storm profile show that the slope is smaller (i.e. increasing dune erosion) as the wave period [math]T[/math] is longer and the fall velocity smaller.

The storm profile method is based on the equilibrium profile concept that also underlies the Bruun rule. However, whereas the Bruun rule refers to the average coastal profile that settles over the long term, the storm profile method refers to storm conditions of limited but sufficient duration so that the most heavily reworked part of the beach and the foredune assumes an approximate equilibrium profile. The Bruun rule assumes that the sand is redistributed over the entire active coastal zone [math]x_{Bruun}[/math] (from foredune to closure depth), which is wider than the storm active zone [math]x_{max}[/math]. A drawback of the storm profile method is that hardly any physics is involved. The development with time of the storm profile is unknown. Effects of varying water levels and varying wave characteristics during the storm surge cannot be accounted for.

Only in exceptional cases do storm surge conditions last long enough to induce profile changes that are close to equilibrium. The empirical profile formulas established from long-term hydraulic model experiments should therefore be considered an upper limit of dune erosion that can occur in naturally occurring extreme storms.

Analytic dune erosion model

A process-based, but highly idealized analytic model was developed by Larson et al. (2004[20]) for estimating the time evolution of dune erosion. This model is based on the assumption that the eroded dune volume [math]\Delta V[/math] in a time interval [math]\Delta t[/math] is proportional to the force [math]F[/math] exerted by swash waves hitting the dune foot. By expressing the force [math]F[/math] as a function of the dune foot height [math]z_D[/math], the maximum water level [math]R[/math] including wave run-up and the wave period [math]T[/math], the following equation was obtained for the loss rate [math]dV/dt[/math] of dune volume (see the appendix and Fig. B1):

[math]\Large\frac{dV}{dt}\normalsize=-4C_s\Large\frac{(R-z_D)^2}{T}\normalsize , \qquad (1)[/math]

where the constant [math]C_s[/math] depends on site-specific characteristics (such as sediment grainsize distribution, beach and foreshore morphology, vegetation, slope of the dune face) and has to be calibrated with field data. As shown in the appendix, the rate of dune erosion according to equation (1) is an increasing function of the wave height, the wave period and the beach slope. This is in line with the dune erosion estimate following from the storm profile of Fig. 6. Equation (1) also shows that dune erosion strongly depends on the height [math]z_D[/math] of the dune foot (thus on the beach steepness and width). This is consistent with observations at Narrabeen-Collaroy Beach (East Australia, near Sidney), which showed that alongshore variability in dune erosion was highly correlated with alongshore variability in [math]z_D[/math][4]. A strong relationship between dune erosion volumes and dune foot height was also found in wave tank experiments[21]. Assuming that the beach slope [math]\beta[/math] remains constant during dune erosion (i.e., dune retreat [math]\Delta x[/math] equal to [math]\Delta z_D / \tan \beta[/math]), Larson et al. (2004[20]) found reasonable agreement with observed dune erosion rates when using values of [math]C_s[/math] in the range 10-3 - 2.10-3.

The analytic model does not include the process of mass failure due to wetting and steepening of the dune face. Dune retreat will thus be underpredicted in situations where this process plays an important role. Ignoring the distinction between the wave run-up and storm level components in the total water level [math]R[/math] is another simplification. Observations of dune erosion on the US northwest coast show that the influence of the storm level component is more important for dune erosion than the wave run-up component[22]. A more elaborate version of the analytic dune erosion model includes the effects of overwash, wind-blown sand transport, and bar-berm material exchange (Larson et al., 2016[23]).

The maximum water level [math]R[/math] is subject to an increasing trend as a result of climate change (including sea level rise). The dune erosion model can therefore be used to estimate the impact of climate change on dune erosion. The associated long-term dune foot retreat can be estimated by making assumptions about post-storm dune recovery. The values for dune foot retreat obtained in this way by Ranasinghe et al. (2012[24]) and Le Cozannet et al. (2019[25]) are higher than the values of coastal retreat obtained with the Bruun rule.

DUNERULE

Based on a large number of numerical model runs, Van Rijn (2009)[26] derived a simple formula for estimating the volume of dune erosion as a function of various parameters representing beach characteristics and hydraulic storm surge conditions. The underlying numerical model, CROSMOR, simulates the major wave transformation and sand transport processes in the surf zone responsible for the evolution of the cross-shore coastal profile, including dune collapse by colliding waves. The model has been extensively tested in small-scale and large-scale laboratory facilities and in natural settings. The DUNERULE formula reads

[math]V(t) = V_5\Large (\frac{t}{t_{ref}})^{\alpha_t} \, (\frac{h}{h_{ref}})^{\alpha_h} \, (\frac{H}{H_{ref}})^{\alpha_H} \, (\frac{T}{T_{ref}})^{\alpha_T} \, (\frac{d_{50}}{d_{50,ref}})^{\alpha_d} \, (\frac{\tan \beta}{\tan \beta_{ref}})^{\alpha_{\beta}}\normalsize \, f(\theta) . \qquad (2) [/math].

The reference values correspond to a heavy storm at the Dutch coast: [math] t_{ref}= 18,000 \, s ; \; h_{ref}= 5 \, m ; \; H_{ref}= 7.6 \, m ; \; T_{ref}= 12 \, s ; \; \tan \beta_{ref}= 0.022; \; d_{50,ref}= 225 \, 10^{-6} \, m ,[/math]

where [math]t[/math] is the storm duration, [math]h[/math] is the average storm surge level including wave set-up, [math]H[/math] the storm significant wave height, [math]T[/math] the peak wave period, [math]d_{50}[/math] the mean sediment grain size, [math]\tan \beta[/math] the average beach slope between the -3 m depth contour and the dune toe (+3 m) and [math]\theta[/math] the wave incidence angle [o].

The coefficients fitted to the CROSMOR simulations are:

[math]V_5=170 \, m^3; \quad \alpha_t=0.5, \, t\lt 18,000; \; \alpha_t=0.2, \, t\gt 18,000; \quad \alpha_h=1.3, \, h\lt 5 ; \alpha_h=0.5, \, h\gt 5; \quad \alpha_H=0.5; \quad \alpha_T=0.5; \quad \alpha_d=1.3; \quad \alpha_{\beta}=0.3 \;[/math] and [math]f(\theta)=(1+0.01 \, \theta)^{0.5} .[/math]

The main advantage of the DUNERULE formula is its simplicity. A constant beach slope is assumed; the effect of slope time dependence is approximated through the exponent [math]\alpha_t[/math]. The formula implicitly takes wave run-up into account. One drawback of DUNERULE is that it does not account for fluctuating storm surge levels, which always occur along meso- and macrotidal coasts in case of long duration storms. Comparison with the analytical dune erosion model shows that DUNERULE produces much larger erosion volumes in case of short duration storms. The erosion volumes become similar for long duration storms, assuming that tidal water level variations can be ignored. Another drawback is the restriction to isolated storms; DUNERULE cannot be applied to storm clusters[27]. In cases of varying storm surge levels and storm clusters, the use of numerical models is required.

XBeach

The dune erosion models considered in the preceding sections represent strong simplifications that ignore specific hydrodynamic processes and bathymetric features that influence the local impact of storms, such as wave spectrum, wave deformation and refraction on morphological structures in the nearshore zone, longshore sand transport, beach morphology and vegetation and dune overwash. More generally applicable and accurate dune erosion forecasts therefore require numerical process-based models that are capable to simulate the effect of such features, also including the effect of storm sequences. An example is the widely used depth-averaged wave spectral XBeach model [28]. This open-source process-based numerical model was originally developed to simulate hydrodynamic and morphodynamic processes and impacts on sandy coasts with a domain size of kilometers and on the time scale of storms and has since been extended to wider applications. The model simulates the hydrodynamic processes of short wave transformation (refraction, shoaling and breaking), long wave transformation (generation, propagation and dissipation of infragravity waves), wave set-up and unsteady currents, overwash and inundation. It includes the effect of wave skewness and asymmetry, the dynamics of nearshore sandbars, as well as the effects of vegetation and hard structures. The morphodynamic processes include bed load and suspended sediment transport, bed update and breaching. The model has been validated with a series of analytical, laboratory and field test cases using a standard set of parameter settings. The slumping of sand slabs from the dune face during storm conditions is taken into account when updating the bed levels. This is modeled through introduction of a critical dune slope (default critical slope of 1 for dry zones and 0.3 for wet zones). When the critical slope is exceeded, material is exchanged between adjacent cells to the amount needed to bring the slope back to the critical slope.

Comparison with observed dune erosion events at the Dutch coast shows that XBeach estimates the magnitude and pattern of alongshore variations in erosion volume reasonably well. The 2014-version of XBeach overpredicted the erosion volume in the region where a dune scarp developed and underestimated the erosion volume where the whole dune face collapsed in a series of slumps [29]. XBeach simulations further illustrated that the observed alongshore variation in dune erosion was steered primarily by the pre-storm dune topography i.e., the presence of embryonic dune fields and the steepness of the dune face. The importance of alongshore variability in intertidal beach topography was found to be secondary, but not negligible during the initial stage of the storm, when the surge level was still low. XBeach simulations further show that storm duration has an important effect on dune erosion[30]. The 2019 version of XBeach was used to simulate the failure process of an experimental unvegetated dune on the German Baltic Sea coast. The post-storm dune breach was simulated well, but dune erosion was overestimated with respect to temporal profile evolution. It was concluded that the XBeach model is able to predict with sufficient accuracy the evolution of storm-induced erosion during a long overwash/inundation-dominant wave event when current high-resolution input data is available[31].

Post-storm dune recovery

After being eroded under storm conditions, the dune front can recover naturally without human intervention. This has been observed for many sandy coasts with either a gently sloping or a steep sloping shoreface [32][33][34]. Strong beach accretion often already occurs during the phase of waning storm intensity. Shoreline recovery is dealt with in the article Shoreline retreat and recovery. It is a much faster process than dune recovery. Fast beach recovery is promoted by landward migration and welding of nearshore (intertidal) sandbars to the beach during fair-weather conditions. Aeolian sand transport to the dune starts once the upper-beach and any washover deposits become dry with the development of embryo dunes on the backshore. The expansion of the backshore is required to increase the fetch length, which controls the amount of sediment exchanged from the beach to the dune. Dune recovery also depends on vegetation recolonization. Post-storm recovery of vegetation can take two to eight years depending on the extent that the roots and rhizomes are impacted[35][36].

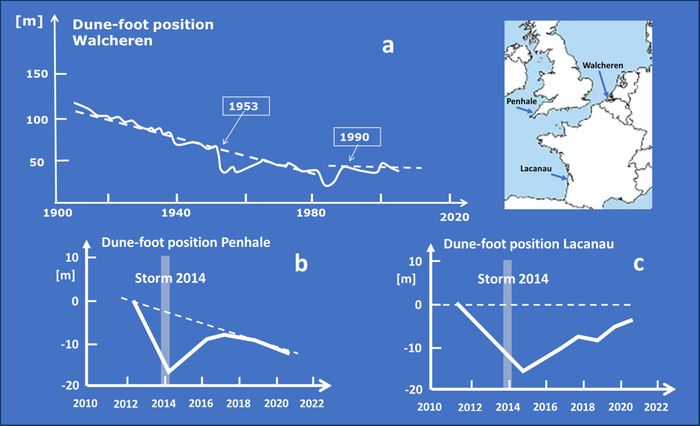

An example of natural dune recovery is shown in Fig. 7a for a naturally retreating coast (Walcheren, the Netherlands). The extreme storm surge of 1953 caused a 30 m retreat of the dune foot. Afterwards the dune foot advanced slightly over a period of several years, until it reached about 15 years later the position corresponding to the retreating trend prior to the storm surge. The ongoing coastal retreat was finally halted in 1990, when the Dutch government decided to stop coastal retreat along the entire coastline with sand nourishments.

Figs. 7b and 7b show examples of dune recovery at two locations (Penhale, UK, and Lacanau, France) on the western European coast, which were severely impacted by the 2014 winter storm. The decade-averaged shoreline retreat in both locations is small, no more than a few meters per decade. The foredune in Penhale is higher than in Lacanau, more densely vegetated (with marram grass) and more alongshore uniform. The 2014 winter storm caused a dune foot retreat of almost 20 m in both locations. The retreat was fairly uniform along the coast at Penhale but showed pronounced erosion hotspots at Lacanau. At Penhale, the dune foot position partially recovered within a few years, but followed afterwards a trend of retreat. At Lacanau, the initial dune foot position was not recovered after 6 years, although a trend towards full recovery was observed. This example illustrates that dune recovery trajectories can differ considerably between sites with only moderately different characteristics.

Dune failure probability

The numerical model XBEACH and the simplified dune erosion models discussed earlier provide estimates for dune retreat under given storm conditions. A highly relevant question is related to the probability of dune failure, i.e., the probability that dune retreat at a certain location exceeds a given value, leading to dune collapse and flood damage to settlements situated behind the dune. To answer this question, knowledge of the probability of extreme storm conditions occurring at this location is required. If the time interval between storms leading to dune failure is much shorter than the length of the available storm data record, the failure probability can be found by estimating the dune retreat for all extreme storm conditions occurring in the dataset. However, dune reinforcement programs usually require knowledge of the statistical return period of possible dune failure that far exceeds the length of available storm records. In this case, the available storm record must be extended by statistical methods to a time span much longer than this return period. This can be done by a method described below[38].

Storm conditions can be characterized by the parameters: maximum significant wave height, wave period, storm surge water level, wave direction, and storm duration. If these parameters are uncorrelated, the parameters corresponding to extreme storms with a given return period exceeding the data record can be estimated by fitting an appropriate cumulative distribution function (marginal cumulative distribution function) to the available storm dataset for each parameter separately. The overall probability is then given by the product of the separate probabilities. However, storm parameters are typically correlated. To account for these correlations, so-called copulas are constructed. Copulas are multivariate cumulative distribution functions for which the marginal probability distribution of each variable is uniform on the interval [0, 1]. Choosing the appropriate copula and determining the copula parameters from the data is often not simple and requires acquaintance with copula theory (see for example McNeil et al. 2005[39]). From the fitted copulas, random samples can be constructed of extreme storm surge conditions with known probabilities. By estimating dune retreat for these random samples (Monte Carlo method) a relation can be established between calamitous dune retreat (dune failure) and the corresponding probability.

Impact of sea-level rise on dune erosion

The XBeach model predicts an approximately linear relationship between dune erosion volume and sea level rise [40]. This is primarily due to the higher water level in front of the dune rather than to changes in the significant short-wave or infragravity wave height. Changes in the offshore angle of wave incidence also affect the dune erosion volume. A 30° shift from shore-normal influences the dune erosion volume to the same extent as a 0.4 m sea-level rise. This increase in dune erosion volume is related to strong alongshore currents, generated as a result of the obliquity of the waves, that enhance stirring and hence offshore transport[40].

XBeach simulations further show that the effectiveness of coastal sand nourishment to mitigate the impact of sea-level rise on dune erosion depends on the location in the profile where this sand is added. The reduction of dune erosion volume relative to the total added nourishment volume never exceeds 30% in the case of shore or beach nourishment. This suggests that directly increasing the volume of sand in the dunes can be more efficient than beach or shoreface nourishment[40].

Appendix: Analytical dune erosion model

The analytic model of Larson et al. (2004[20]) is a crude simplification of the dune erosion process. However, it does allow an estimate of the order of magnitude of the eroded dune volume under severe storms for different beach morphologies. The model is based on the following assumptions and simplifications:

- The eroded dune volume [math]\Delta V[/math] in a time interval [math]\Delta t[/math] is proportional to the force [math]F[/math] exerted by swash waves hitting the dune foot, [math]\Delta V \propto F \Delta t .[/math]

- The force [math]F \Delta t [/math] is proportional to the number of swash bores [math]n[/math] hitting the dune foot ([math]n=\Delta t/T[/math]) and the force exerted by each individual swash bore, [math]f=m \Large\frac{du}{dt}\normalsize \propto \Large\frac{mu}{T}\normalsize [/math], where [math]T[/math] is the wave period, [math]m[/math] the mass of the swash bore per unit dune width and [math]u[/math] the velocity of the swash bore when hitting the dune foot.

- The bore height [math]h[/math] is related to the bore velocity by [math]u \propto \sqrt{gh}[/math], where [math]g[/math] is the gravitational acceleration. The bore mass is thus proportional to [math]m \propto huT \propto u^3 T[/math], yielding [math]F = n \,f / \Delta t \propto u^4 /T[/math].

- The bore velocity at the dune foot can be related to the swash runup [math]R[/math]. A ballistic swash excursion model (neglecting friction) gives an estimate for this relation, [math]R=z_D+gu^2/2[/math], where [math]z_D[/math] is the height of the dune foot compared to the beach level where waves collapse on the beach. Using this relation, the force [math] F [/math] can be expressed as a function of the wave runup [math] R [/math], [math]F \propto (R – z_D)^2 / T[/math].

- Substitution with [math]\Delta V / \Delta t \approx dV/dt [/math] gives Eq. (1), where [math]C_s[/math] is a proportionality constant, depending on characteristics of the site, such as sediment grainsize, wave incidence angle, shoreface profile, etc. The value of [math]C_s[/math] should be calibrated with local field data.

- Empirical expressions for the wave run-up [math]R[/math] are given in the article Wave run-up. However, the 2% wave run-up may not be the most pertinent parameter; less extreme thresholds may be more effective for dune erosion[3].

Wave run-up increases with increasing offshore wave height [math]H[/math], increasing wave period [math]T[/math] and increasing beach slope [math]\tan \beta[/math]. From Eq. (1) it then appears that the rate of dune erosion increases as the wave height [math]H[/math] increases, the wave period [math]T[/math] increases, the beach slope [math]\beta[/math] increases and the beach width [math]l[/math] decreases. Greater dune erosion for steeper beaches under the same wave conditions is consistent with observations[22].

The dune foot height [math]z_D[/math] (relative to the beach level of wave collapse [math]z_C[/math]) and the beach slope [math]\beta[/math] are time dependent. In order to solve Eq. (1) a prescription must be given how the eroded dune material is distributed over the beach – i.e. a model for the dependence of [math]z_D[/math] and [math]\beta[/math] on [math]dV/dt[/math]. Based on experiments in large wave flumes, Larson et al. (2004[20]) assumed that the beach slope [math]\beta[/math] remains constant during dune erosion. The dune retreat [math]\Delta x[/math] was therefore set equal to [math]\Delta z_D / \tan \beta[/math], assuming that the major part of the dune volume loss is removed to the lower beach (below the level of wave collapse). Field observations of dune erosion events in different sites along coasts in the USA, Australia and France show that the upper beach slope can vary considerably depending on site characteristics and storm intensity[3]. These observations emphasize the tentative nature of the analytical model.

Considering a dune height [math]D[/math] above the level of wave collapse [math]z_C[/math] (the scarp height), the loss of dune volume is given by [math]\Delta V=-(D-z_D) \Delta x = -(D- z_D) \Delta z_D / \tan \beta[/math]. Combining this result with Eq. (1) yields a differential equation for the dune foot height [math]z_D[/math]:

[math]\Large\frac{d}{dt}\normalsize z_D = \Large\frac{1}{\tau} \frac{(R-z_D)^2}{D-z_D}\normalsize , [/math] where [math]\tau=T/(4 C_s \tan \beta)[/math].

If it is further assumed that the level of wave collapse [math]z_C[/math] does not change during the storm, then the wave run-up remains constant too (the slope [math]\beta[/math] was assumed constant). For storms of limited duration the run-up [math]R[/math] can be assumed constant. The differential equation can then be solved, with solution

[math]t = \tau (D-R)\Large(\frac{1}{R-z_D(t)} - \frac{1}{R-z_D(0)})\normalsize +\tau \ln\Large\frac{R-z_D(0)}{R-z_D(t)}\normalsize [/math], from which [math]z_D(t)[/math] and [math]V(t)[/math] can be derived.

Related articles

- Natural causes of coastal erosion

- Dune stabilisation

- Light revetments built-in into artificial dunes

- Shoreface profile

- Bruun rule

- Active coastal zone

- Dune development

- Shoreline retreat and recovery

- Swash zone dynamics

- Shore protection vegetation

- Dynamics, threats and management of dunes

- Risk and coastal zone policy: example from the Netherlands

References

- ↑ Anthony, E.J., Mrani-Alaoui. M. and Héquette, A. 2010. Shoreface sand supply and mid- to late Holocene aeolian dune formation on the storm-dominated macrotidal coast of the southern North Sea. Marine Geology 276: 100–104

- ↑ Den Heijer, C. 2013. The role of bathymetry, wave obliquity and coastal curvature in dune erosion prediction. PhD Thesis, Delft University

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Conlin, M.P., Cohn, N. and Adams, P.N. 2023. Total water level controls on the trajectory of dune toe retreat. Geomorphology 438, 108826

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Splinter, K.D., Kearney, E.T. and Turner, I.L. 2018. Drivers of alongshore variable dune erosion during a storm event: Observations and modelling. Coastal Engineering 131: 31–41 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "S18" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Burvingt, O. and Castelle, B. 2023. Storm response and multi-annual recovery of eight coastal dunes spread along the Atlantic coast of Europe. Geomorphology 435, 108735

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Masselink, G. and van Heteren, S. 2014. Response of wave-dominated and mixed-energy barriers to storms. Marine Geology 352 (2014) 321–347

- ↑ Karunarathna, H., Pender, D., Ranasinghe, R., Short, A. D. and Reeve, D. E. 2014. The effects of storm clustering on beach profile variability. Mar. Geol. 348: 103–112

- ↑ Baldock, T.E., Gravois, U., Callaghan, D.P. and Nichol, S. 2021. Methodology for estimating return intervals for storm demand and dune recession by clustered and non-clustered morphological events. Coastal Engineering 168, 103924

- ↑ Galiatsatou, P. and Prinos, P. 2016. Joint probability analysis of extreme wave heights and storm surges in the Aegean sea in a changing climate. In: FLOODrisk 2016-3rd European Conference on Flood Risk Management

- ↑ Luijendijk, A.P., Ranasinghe, R., de Schipper, M.A., Huisman, B.A., Swinkels, C.M., Walstra, D,J,R. and Stive, M.J.F. 2017. The initial morphological response of the Sand Engine: A process-based modelling study. Coastal Engineering 119: 1–14

- ↑ Gerdes, E., Koning, R., Kort, M. and Soomers, H. 2021. Policy evaluation Sand Engine 2021. Rebel Economics & Transactions, report commissioned by Rijkswaterstaat, Netherlands

- ↑ Conti, S., Splinter, K. D., Booth, E., Djadjiguna, D. and Turner, I. L. 2024. Observations on the role of internal sand moisture dynamics in wave-driven dune face erosion. Geomorphology 462, 109331

- ↑ Pinyol, N. M., Alonso, E. E. and Olivella, S. 2008. Rapid drawdown in slopes and embankments. Water Resour. Res. 44, W00D03

- ↑ Erikson, Li, H., Larson, M. and Hanson, H. 2007. Laboratory investigation of beach scarp and dune recession due to notching and subsequent failure. Marine Geology 245: 1–19

- ↑ Conti, S., Splinter, K. D. and Turner, I. L. 2025. Geotechnical stability analysis of dune face erosion by waves. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 130, e2024JF008160

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 van Wiechen, P. P. J., Mieras, R., Tissier, M. F. S. and de Vries, S. 2024. Coastal dune erosion and slumping processes in the swash‐dune collision regime based on field measurements. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 129, e2024JF007711

- ↑ van Wiegen, P.P.J., de Vries, S. and Reniers, A.J.H.M. 2024. Field observations of wave-averaged suspended sediment concentrations in the inner surf zone with varying storm conditions. Marine Geology 473, 107302

- ↑ van Wiechen, P.P.J., de Vries, S., Reniers, A.J.H.M. and Aarninkhof, S.G.J. 2023. Dune erosion during storm surges: A review of the observations, physics and modelling of the collision regime. Coastal Engineering 186, 104383

- ↑ van Gent, M.R.A., van Thiel de Vries, J.S.M., Coeveld, E.M., de Vroeg, J.H. and van de Graaff, J. 2008. Large-scale dune erosion tests to study the influence of wave periods Coastal Engineering 55: 1041–1051

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Larson, M., Erikson, L. and Hanson, H. 2004. An analytical model to predict dune erosion due to wave impact. Coastal Engineering 51: 675– 696

- ↑ Palmsten, M.L. and Holman, R.A. 2012. Laboratory investigation of dune erosion using stereo video. Coastal Engineering 60: 123–135

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Cohn, N., Ruggiero, P., García-Medina, G., Anderson, D., Serafin, K.A. and Biel, R. 2019. Environmental and morphologic controls on wave-induced dune response. Geomorphology 329: 108–128

- ↑ Larson, M., Palalane, J., Fredriksson, F. and Hanson, H. 2016. Simulating cross-shore material exchange at decadal scale. Theory and model component validation. Coastal Engineering 116: 57–66

- ↑ Ranasinghe, R., Callaghan, D. and Stive, M. J. 2012. Estimating coastal recession due to sea level rise: beyond the Bruun rule. Climatic Change 110: 561–574

- ↑ Le Cozannet, G., Bulteau, T., Castelle, B., Ranasinghe, R., Wöppelmann, G., Rohmer, J., Bernon, N., Idier, D., Louisor, J. and Salas-y-Mélia, D. 2019. Quantifying uncertainties of sandy shoreline change projections as sea level rises. Nature Scientific Reports 9:42

- ↑ van Rijn, L.C. 2009. Prediction of dune erosion due to storms. Coastal Engineering 56: 441-457

- ↑ Baldock, T.E., Gravois, U., Callaghan, D.P., Davies, G., Nichol, S. 2021. Methodology for estimating return intervals for storm demand and dune recession by clustered and non-clustered morphological events. Coastal Engineering 168, September 2021, 103924

- ↑ https://xbeach.readthedocs.io/en/latest/user_manual.html

- ↑ De Winter, R.C,. Gongriep, F. and Ruessink, B.G. 2014. Observations and modeling of alongshore variability in dune erosion at Egmond aan Zee, the Netherlands. Coastal Engineering 99: 167-175.

- ↑ Garzon, J. L., Plomaritis, T. A. and Ferreira, O. 2023. Uncertainty analysis related to beach morphology and storm duration for more reliable early warning systems for coastal hazards. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 128, e2022JC019339

- ↑ Schweiger, C., Kaehler, C., Koldrack, N. and Schuettrumpf, H. 2020. Spatial and temporal evaluation of storm-induced erosion modelling based on a two-dimensional field case including an artificial unvegetated research dune. Coastal Engineering 161, 103752

- ↑ Vousdoukas, M.I., Pedro, L., Almeida, M. and Ferreira, O. 2012. Beach erosion and recovery during consecutive storms at a steep-sloping, meso-tidal beach. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 37: 583–593

- ↑ Scott. T., Masselink, G., O'Hare, T., Saulter, A., Poate, T,. Russell. P., Davidson, M. and Conley, D. 2016. The extreme 2013/2014 winter storms: Beach recovery along the southwest coast of England. Marine Geology 382: 224–241

- ↑ Phillips, M.S., Harley, M.D., Turner, I.L., Splinter, K.D. and Cox , R.J. 2017. Shoreline recovery on wave-dominated sandy coastlines: the role of sandbar morphodynamics and nearshore wave parameters. Marine Geology 385: 146–159

- ↑ Suanez, S., Cariolet, J-M., Cancouët, R., Ardhuin, F. and Delacourt, C. 2012. Dune recovery after storm erosion on a high-energy beach: Vougot Beach, Brittany (France). Geomorphology 139-140: 16–33

- ↑ Houser, C., Wernette, P., Rentschlar, E., Jones, H., Hammond, B. and Trimble, S. 2015. Post storm beach and dune recovery: implications for barrier island resilience. Geomorphology 234: 54–63

- ↑ Jeuken, C., Ruessink, G. and Marchand, M. 2001. Ruimtelijke en temporele aspecten van de duinvoetdynamiek. Report WL/Delft Hydraulics Z2838 (in Dutch)

- ↑ Li, F., van Gelder, P.H.A.J.M., Vrijling, J.K., Callaghan, D.P., Jongejan, R.B. and Ranasinghe, R. 2014. Probabilistic estimation of coastal dune erosion and recession by statistical simulation of storm events. Applied Ocean Research 47: 53–62

- ↑ McNeil, A., Frey, R. and Embrechts, P. 2005. Quantitative Risk Management: Concepts, Techniques and Tools. Princeton University Press

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 De Winter, R,C. and Ruessink, B.G. 2017. Sensitivity analysis of climate change impacts on dune erosion: case study for the Dutch Holland coast. Climatic Change (2017) 141:685–701 DOI 10.1007/s10584-017-1922-3

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|