Bruun rule for shoreface adaptation to sea-level rise

Contents

The equilibrium profile concept

The basic idea of Per Bruun when he proposed in 1954 the rule for shoreface adaptation to sea-level rise refers to the concept of equilibrium profile [1][2]. The shoreface of a sedimentary coast should not be considered a geologically inherited feature, but the result of the natural coastal response to modern hydrodynamic conditions, as noted already more than a century ago by Cornaglia (1889) [3] and Fenneman (1902) [4]. For a more detailed explanation, see the article Shoreface profile.

If climate change affects only the sea level, while leaving the wave climate unchanged, Bruun reasoned that the slope of the equilibrium shoreface profile [math]Z_{eq} (x) [/math] then should also remain the same. The profile should move landward and upward, however, to keep the same position with respect to sea level as before.

An equilibrium profile is a theoretical concept that is never realized in practice at a given time and location. Sand is transported all the time up or down the active zone of the shoreface in response to fluctuations in the wave climate. Sand can also be supplied or taken away as a result of gradients in the longshore sand transport. However, we may consider larger temporal and spatial scales because sea level rise is a slow process on a large spatial scale. Fluctuations in the wave climate generally occur on much shorter time scales. Considering long coastal stretches with similar characteristics (far from headlands or coastal inlets), the average gradient of the longshore sand transport decreases with increasing longshore length scale and can become almost insignificant. Hence, if we take the average of the coastal profiles over temporal and spatial scales which are sufficiently long, the resulting profile may be close to equilibrium. This averaged quasi-equilibrium profile then should be preserved while moving landward and upward with sea level rise if the averaging scales are long enough but much shorter than the temporal and spatial scales of sea level rise.

Lifting the profile requires supply of sand. Bruun assumed that sand supply from offshore is negligible if the shoreface profile extends seaward up to the closure depth. The sand should then be supplied from the coastal profile that lies inland from the active coastal profile, for example a high berm, a (fore)dune or a sand barrier. This can only be the case if the sea level does not exceed the elevation of the inland coastal profile. It also must be assumed that the sediment supplied by the inland part of the coastal profile has characteristics similar to the sand of the active coastal zone.

Mathematical expression of the Bruun rule

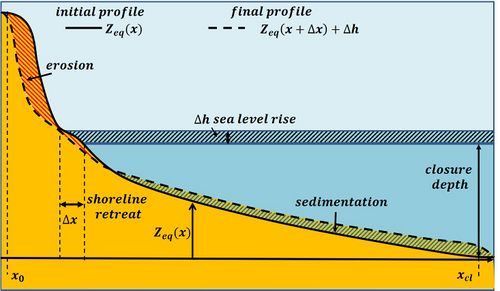

Sand supply from the inland coastal profile implies shoreline retreat (designated [math]\Delta x[/math]) and a corresponding landward shift of the equilibrium shoreface profile. The new translated equilibrium profile [math]Z^{new}_{eq} (x)[/math] is then equal to the old equilibrium profile [math]Z_{eq} (x)[/math] with an upward shift equal to the sea-level rise [math]\Delta h[/math], and a landward shift [math]\Delta x[/math] (see Fig. 1):

[math]Z^{new}_{eq} (x) = Z_{eq} (x+\Delta x) + \Delta h . \qquad(1)[/math]

The shoreline retreat [math]\Delta x[/math] can be computed by the requirement that the total sand volume in the active zone (between [math]x_0[/math] and [math]x_{cl}[/math], see Fig. 1) remains the same:

[math]\int_{x_0}^{x_{cl}} [Z_{eq} (x+\Delta x) + \Delta h] dx = \int_{x_0}^{x_{cl}} Z_{eq} (x) dx . \qquad(2)[/math]

Note that the equilibrium shoreface profile [math]Z_{eq} (x)[/math] is defined here relative to the closure depth. It is assumed that [math]\Delta x[/math] is small ([math]\Delta x \lt \lt x_{cl} – x_0[/math]). We therefore have ignored the small shift of the limits of the active zone in Eq. (2) and we further approximate

[math]Z_{eq} (x+\Delta x) \approx Z_{eq} (x) + \Delta x \; \Large \frac{d Z_{eq} (x)}{dx} \normalsize . \qquad(3)[/math]

Substitution in equation (2) then yields for the horizontal landward shoreline shift [math]\Delta x[/math] the Bruun rule

[math]\Delta x \approx \Delta h \; \Large \frac{x_{cl} – x_0}{Z_{eq} (x_0)} \normalsize . \qquad(4)[/math]

Conditions and limitations for application of the Bruun rule

Evidence for the Bruun hypothesis

Laboratory experiments of shoreface profile adaptation to sea-level rise show reasonable agreement with the Bruun rule if time scales are considered which are sufficiently long for the development of an equilibrium profile[5].

Beach-dune profiles have been monitored annually over the past 50 years in Australia, the eastern USA, Japan, the Baltic Sea and the Netherlands at various coastal sites where the natural evolution is not significantly perturbed by human interventions. None of these profiles show a trend that can be attributed with any certainty to the 10-15 cm sea level rise over this period. In fact, the effects of seasonal, interannual and long-term marine and climatic conditions on beach dune morphology appear to be dwarfed by the incidence of episodic but frequent storms of moderate intensity[6]. The current rate of sea level rise is not yet high enough to observe in practice a general trend in coastal retreat that can be clearly attributed to sea level rise.

In addition to long time scales, the application of the Bruun rule also requires large spatial scales. At local scales, natural processes can cause trends in coastal change that deviate significantly from the average trend over long coastal stretches - examples are given in the article Erosion hotspots.

External sand sources and sinks

The Bruun rule has been widely applied, but the results did often not compare very well to observations. Critical comments have been written on the Bruun rule [7]. A major reason for discrepancies results from ignoring the assumptions underlying the derivation of the Bruun rule. This holds in particular for the assumption that the sand volume in the active coastal profile remains unchanged: sand supply from other sources and sand losses are not considered. However, the Bruun rule can be extended to include to some degree other sand sources and sand losses that occur during profile translation[8][9][10]. Therefore the volume change [math]\Delta V[/math] [[math]m^3/m[/math]] of the active coastal profile due to sand loss (positive) or sand supply (negative) during sea level rise should be added in the left hand side of Eq. (2). We then find for the horizontal landward shoreline shift [math]\Delta x[/math]:

[math]\Delta x \approx \Delta h \; \Large \frac{x_{cl} – x_0}{Z_{eq} (x_0)} + \frac{\Delta V}{Z_{eq} (x_0)} \normalsize . \qquad(5)[/math]

Causes of sand loss and sand supply are:

- Sand loss to the dunes, by aeolian transport;

- Incidental overwash of low coastal barriers by overtopping waves;

- Transport across the closure depth contour;

- Gradients in longshore transport;

- Artificial coastal nourishment.

However, these loss and supply volumes should not be very important, as they would otherwise alter the average shape of the coastal profile. With this restriction, Eq. (5) suggests that sand nourishment of sufficient volume (depending on the rate of sea level rise and the width of the active coastal zone), can neutralize shoreline retreat if applied to any location of the active coastal profile over a sufficient longshore length.

Knowledge of the closure depth

Application of the Bruun rule requires knowledge of the closure depth under natural conditions with respect to the considered time scale. Determining the closing depth is not straightforward as explained in the article Closure depth. Several formulas have been proposed, but there is no universal prescription that applies to every type of coast. The problem of choosing the correct closure depth introduces an important uncertainty in the application of the Bruun rule.

Human interventions

It is clear that the Bruun rule cannot be applied if the equilibrium conditions for the coastal profile are significantly changed due to human interventions, for example:

- change of the local wave climate due to construction of artificial islands, offshore windfarms, dredging of navigation channels or offshore deposition of dredged material;

- change in sand supply due to dam building in nearby rivers, construction of jetties or groynes.

Coastal squeeze

Application of the Bruun rule assumes that the sand needed for an upward shift of the beach profile can be provided by a landward source. Therefore, the Bruun rule for shoreline retreat cannot be applied in cases where the landward boundary of the active zone is bounded by a hard structure, for example a rocky cliff or an artificial sea wall, a situation usually referred to as 'coastal squeeze'. If there is no sand supply from landward sources, sea level rise will lead to a gradual ongoing submergence of the subaerial beach, starting with beach lowering adjacent to the sea wall.[11].

The Bruun rule can be applied under certain conditions if the active zone is bounded by a soft cliff. Cliff erosion during sea level rise should yield an amount of sand that is sufficient for lifting the active coastal profile; cliff retreat then depends on the cliff slope and the sand content[12]. Another condition implies that cliff erosion should not release coarse material that changes the beach sediment characteristics and thus modifies the equilibrium profile.

Wave climate

If climate change causes not only a rise in sea level, but also a change in the wave climate, then the Bruun rule cannot be applied[13].

Related articles

- Sea level rise

- Shoreface profile

- Active coastal zone

- Closure depth

- Natural causes of coastal erosion

- Effect of climate change on coastline evolution

- Dealing with coastal erosion

- Dune erosion

References

- ↑ Bruun, P. 1954. Coast erosion and the development of beach profiles. Beach Erosion Board, US Army Corps of Eng., Tech.Mem. 44: 1-79

- ↑ Bruun, P. 1962. Sea-level rise as a cause of shore erosion. Proc.Am.Soc.Civ.Eng., J.Water Harbors Div. 88: 117-130.

- ↑ Cornaglia, P. 1889. Delle Spiaggie. Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Atti.Cl.Sci.Fis., Mat.e Nat.Mem. 5: 284-304

- ↑ Fenneman, N. M. 1902. Development of the profile of equilibrium of the subaqueous shore terrace. J. Geol., 10(1), 1–32.

- ↑ Atkinson, A.L., Baldock T. E., Birrien, F., Callaghan, D. P., Nielsen, P., Beuzen, T., Turner, I.L., Blenkinsopp, C. E. and Ranasinghe, R. 2018. Laboratory investigation of the Bruun Rule and beach response to sea level rise. Coastal Engineering 136: 183–202

- ↑ McLean, R., Thom, B., Shen, J. and Oliver, T. 2023. 50 years of beach–foredune change on the southeastern coast of Australia: Bengello Beach, Moruya, NSW, 1972–2022. Geomorphology 439, 108850

- ↑ Cooper, J.A. and Pilkey, O.H. 2004. Sea-level rise and shoreline retreat: time to abandon the Bruun Rule. Global Planetary Change 43: 157-171

- ↑ Stive, M.J.F. 2004. How Important is Global Warming for Coastal Erosion? Climatic Change 64: 27–39

- ↑ Rosati, J.D., Dean, R.G. and Walton, T.L. 2013. The modified Bruun Rule extended for landward transport. Mar. Geol. 340: 71-81

- ↑ Dean, R.G. and Houston, J.R. 2016. Determining shoreline response to sea level rise. Coastal Engineering 114: 1–8

- ↑ Beuzen, T., Turner, I.L., Blenkinsopp, C.E., Atkinson, A., Flocard, F. and Baldock, T.E. 2018. Physical model study of beach profile evolution by sea level rise in the presence of seawalls. Coast. Eng. 136: 172–182

- ↑ Wolinsky, M.A. and Murray, A.B. 2009. A unifying framework for shoreline migration: 2. Application to wave-dominated coasts. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 114: F01009

- ↑ Masselink, G., Brooks, S., Poate, T., Stokes, C. and Scott, T. 2022. Coastal dune dynamics in embayed settings with sea-level rise – Examples from the exposed and macrotidal north coast of SW England. Marine Geology 450, 106853

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|