Difference between revisions of "Wave run-up"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | |||

{{Definition|title=Wave run-up | {{Definition|title=Wave run-up | ||

|definition= Wave run-up is the maximum onshore elevation reached by waves, relative to the shoreline position in the absence of waves.}} | |definition= Wave run-up is the maximum onshore elevation reached by waves, relative to the shoreline position in the absence of waves.}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

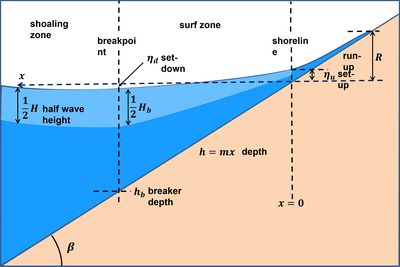

| − | + | [[File:SetupRunup.jpg|thumb|400px|left|Fig. 1. Definition sketch wave set-down, wave set-up and wave run-up.]] | |

| + | |||

| + | Wave run-up on the beach is the sum of [[wave set-up]] and [[swash]] uprush and must be added to the water level elevation resulting from tides, wind stress, air pressure and other oceanographic processes (Fig. 1). Wave run-up results from the momentum carried by waves when they collapse or surge onto the beach. Short, wind-generated waves turn into uprushing [[swash]] bores. Wave run-up is an important phenomenon for assessing the safety of sea dikes or coastal settlements. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wave run-up refers to waves generated by wind (locally or on the ocean) or waves generated by incidental disturbances of the sea surface such as tsunamis, seiches or ship waves. Wave run-up is usually indicated with the symbol <math>R</math>. It is often represented by the 2 % exceedance level <math>R_2</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many empirical formulas for the wave run-up have been derived from laboratory and field data, some of which are reproduced in the paragraph below. Most formulas consider the wave height <math>H</math>, the wavelength <math>L</math> and the foreshore slope <math>\tan \beta</math> as most relevant parameters. When comparing with field measurements, a much greater variability (up to about 50%) is generally observed than can be explained by variations in <math>H</math>, <math>L</math> and <math>\tan \beta</math>.<ref name=A17>Atkinson, A.L., Power, H.E., Moura, T., Hammond, T., Callaghan, D.P. and Baldock, T.E. 2017. Assessment of runup predictions by empirical models on non-truncated beaches on the south-east Australian coast. Coast. Eng. 119: 15–31</ref> This can likely be (partially) explained by variability in the morphology of the upper shoreface, such as the presence/absence of rip channels, rip head bars, longshore or transverse sand bars. These morphological features seem to be particularly relevant for the infragravity component of the swash uprush. <ref>Gracia-Barrera, A.D., Ruiz de Alegría-Arzaburu, A., Coco, G., Simarro, G. and Calvete, D. 2025. Alongshore runup variability across contrasting beach states: Insights from field observations. Geomorphology 473, 109640</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Empirical formulas sandy beaches== | ||

| + | For regular waves collapsing on the beach, a first order-of-magnitude estimate is given by the empirical formula of Hunt (1959) <ref name=H59>Hunt, I.A. 1959. Design of seawalls and breakwaters. J. Waterw. Harbors Division ASCE 85: 123–152</ref><ref>Holman, R.A. and Sallenger, A.H. 1985. Setup and swash on a natural beach. J. Geophys. Res. 90: 945–953</ref><ref name=A17>Atkinson, A.L., Power, H.E., Moura, T., Hammond, T., Callaghan, D.P. and Baldock, T.E. 2017. Assessment of runup predictions by empirical models on non-truncated beaches on the south-east Australian coast. Coast. Eng. 119: 15–31</ref>, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>R \sim \eta_u + H \xi , \qquad (1)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>\eta_u \sim 0.2 H</math> is the [[wave set-up]], <math>H</math> is the offshore significant wave height and <math>\xi</math> is the [[surf similarity parameter]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\xi = \Large\frac{\beta}{\sqrt{H/L}}\normalsize = T \, \beta \, \Large\sqrt{\frac{g}{2\pi H}}\normalsize , \qquad (2)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>\tan \beta \approx \beta</math> is the beach slope and <math>T</math> is the peak wave period. The offshore wavelength <math>L</math> is given by <math>L = g T^2/(2 \pi)</math>, assuming that <math>L / (2 \pi) </math> is smaller than the local depth <math>h</math>. | ||

| + | The horizontal wave incursion is approximately given by <math>R / \beta</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The maximum run-up depends on the mean water level at the shoreline. This water level is increased by wave-induced setup <math>\eta_0</math>, see [[Wave set-up]]. The following empirical relationship has been derived for the sum of maximum wave setup and swash runup<ref name=S6>Stockdon, H.F., Holman, R.A., Howd, P.A. and Sallenger, A.H. 2006. Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coast. Eng. 53: 573–588</ref>: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> R \approx 0.73 \; \beta \; \sqrt{HL} . \qquad (3)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many empirical formulas have been proposed for the run-up. A popular formula for the run-up <math> R_2</math> exceeded by only 2 % of the waves for given <math>H, L</math> has been developed by Stockdon et al. (2006<ref name=S6>Stockdon, H.F., Holman, R.A., Howd, P.A. and Sallenger, A.H. 2006. Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coast. Eng. 53: 573–588</ref>), based on a large dataset: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> R_2 = 1.1 \; (\eta_u + 0.5 \sqrt{S_w^2 + S_{ig}^2} \, ) , \qquad \xi \ge 0.3 , \qquad R_2= 0.043 \; \sqrt{HL} , \qquad \xi < 0.3 , \qquad (4) </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>\eta_u = 0.35 H \xi</math> is the wave set-up, <math>S_w=0.75 H \xi</math> is the swash uprush related to incident waves and <math>S_{ig}=0.06 \sqrt{HL}</math> is the additional uprush related to [[infragravity waves]]. The factor 1.1 takes into account the non-Gaussian distribution of run-up events. | ||

| + | |||

| + | An empirical expression taking the medium sediment grain size <math>d_{50}</math> [m] into account is<ref name=H59/><ref>Sunamura,T. 2004. A predictive relationship for the spacing of beach cusps in nature. Coastal Engineering 51: 697-711</ref>, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>R = 0.4 \beta \,T \, \sqrt{gH} \, \exp(-10 \, d_{50}^{0.55}) \, . \qquad (5) </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This formula is less suitable for dissipative beaches, where swash is dominated by infragravity waves. In this case a dependence on the square root of the beach (swash) slope should be preferred, e.g. <math>\,\eta_u = (0.2-0.3) \, \sqrt{\beta \, H_s \, L} \,</math> <ref>Medellín, G., Brinkkemper, J.A., Torres-Freyermuth, A., Appendini, C.M., Mendoza, E.T. and Salles, P. 2016. Run-up parameterization and beach vulnerability assessment on a barrier island: a downscaling approach. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 16: 167–180</ref><ref>Gomes da Silva, P., Medina, R., González, M. and Garnier, R. 2018. Infragravity swash parameterization on beaches: the role of the profile shape and the morphodynamic beach state. Coast. Eng. 136: 41–55 </ref>. Other studies find that run-up dominated by [[infragravity waves]] is generally small and increases with increasing wave height (approximately linear dependence<ref>Ruessink, B.G., Kleinhans, M.G. and Van Den Beukel, P.G.L. 1998. Observations of swash under highly dissipative conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 103: 3111–3118</ref><ref>Ruggiero, P., Holman, R. A. and Beach, R. A. 2004. Wave run-up on a high-energy dissipative beach. J. Geophys. Res. 109, C06025, doi:10.1029/2003JC002160</ref>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | From an inventory of run-up formulas by Gomes da Silva et al. (2020<ref>Gomes da Silva, P., Coco, G., Garnier, R. and Klein, A.H.F. 2020. On the prediction of runup, setup and swash on beaches. Earth-Science Reviews 204, 103148</ref>), it appears that for steep beaches (<math> \beta > 0.1</math>) the run-up increases with increasing beach slope (approximately linear dependance<ref name=NH>Nielsen, P. and Hanslow, D.J. 1991. Wave runup distributions on natural beaches. J. Coast. Res. 7: 1139–1152</ref>), while for gently sloping dissipative beaches (<math> \beta < 0.1</math>) the dependence on beach slope is weak or absent<ref name=NH/><ref name=S6/>. Field observations<ref>Matsuba, Y. and Shimozono, T. 2021. Analysis of the contributing factors to infragravity swash based on long-term observations. Coastal Engineering 169, 103957</ref> and numerical models<ref>Guza, R.T. and Feddersen, F. 2012. Effect of wave frequency and directional spread on shoreline runup. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39: 1–5</ref> point to a dependence of infragravity [[swash]] on the frequency spread and the directional spread of incident waves. The largest infragravity swash has been observed for incident waves with a small directional spread and a large frequency spread. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Run-up on mixed sand-cobble beaches== | ||

| + | Mixed sand-cobble beaches have a sandy upper shoreface and lower beach with typical slopes of 0.01-0.05 that dissipate most shortwave energy. The upper beach, in contrast, has a steep berm with a slope of 0.1-0.25 and is composed of coarse sediment. Due to cobble roughness, swash infiltration and reflection, backwash velocities are small. These beaches therefore tend to be stable, especially since cobble berms can also dynamically adjust to wave impacts (see [[Stability of rubble mound breakwaters and shore revetments]]). Sandy beach run-up formulas overpredict run-up on mixed beaches by ignoring the effects of increased percolation, reflection and roughness. Run-up observations on mixed sand-cobble beaches by Conlin et al. (2025<ref>Conlin, M.P., Wilson,G., Bond, H., Ardag, G. and Arnowil, C. 2025. Predicting wave runup on composite beaches. Coastal Engineering 199, 104743</ref>) were best simulated with the empirical expression | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>R_2 = 1.3 \, (\eta_u + ½ S)\, , \quad \eta_u = 0.92 \, \beta \, H_s^{0.7}\, L^{0.3} \, , \quad S = 1.28 + 3 \, \beta \, H_s \, . \qquad (6)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Accuracy of run-up estimates== | ||

| + | The accuracy (root-mean-square deviation) of run-up predictions using empirical formulas such as (1), (3) or (4) is usually not better than <math>0.25 \, R</math>.<ref name=A17/> The general applicability of empirical formulas for run-up prediction based on simple parametric representations of beach and shoreface is limited due to the influence of the more detailed characteristics of the local beach and shoreface bathymetry (e.g., beach permeability and groundwater level, curvature of the beach profile, crescentic bars, or swash acceleration along the horn of a [[Beach cusps|beach cusp]] embayment<ref>Kim, L.N., Brodie, K.L., Cohn, N.T., Giddings, S.N. and Merrifield, M. 2023. Observations of beach change and runup, and the performance of empirical runup parameterizations during large storm events. Coastal Engineering 184, 104357</ref>). The tide level may influence the wave run-up due to wave breaking on [[nearshore sandbars]].<ref>Guedes, R.M.C., Bryan, K.R., Coco, G. and Holman, R.A. 2011. The effects of tides on swash statistics on an intermediate beach. J. Geophys. Res. 116, C04008</ref> The applicability of empirical formulas for the [[wave set-up]], which is a substantial component of the run-up, is limited for similar reasons. Accurate estimates of the wave run-up require in-situ observations or detailed numerical models. A more detailed discussion of wave run-up and backwash is given in the articles [[Swash]] and [[Swash zone dynamics]]. An analytical model estimate of the runup of monochromatic non-broken waves on a uniform sloping beach is discussed in the article [[Waves on a sloping bed]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Run-up saturation== | ||

| + | The empirical formulas suggest that the run-up is an ever increasing function of the incident wave height. Field and laboratory observations show that this is not the case<ref name=G84>Guza, R.T., Thornton, E.B. and Holman, R.A. 1984. Swash on steep and shallow beaches. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference Coastal Engineering, ASCE, 1, pp. 708 – 723</ref><ref name=H17>Hughes, M.G., Baldock, T.E. and Aagaard, T. 2017. Swash saturation: is it universal and do we have an appropriate model? Coastal Dynamics Conf. 2017, Paper No.108, pp. 192-203</ref>. Several processes limit the uprush on the beach when incident waves are very high: breaking of short waves in the surf zone (leading to surf zone saturation), breaking of infragravity waves on the beach face and collision of the uprushing swash bore with the backwash of the preceding swash bore. More details can be found in the articles [[Swash]], [[Swash zone dynamics]] and [[Breaker index]]. The greatest wave run-up occurs for the highest waves that do not break, which are generally waves in the lower part of the wave frequency spectrum (long-period waves). Theoretical formulas for run-up saturation (for monochromatic frictionless waves, see the articles [[Waves on a sloping bed]], [[Swash]]) have the form | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>R < R_s = A \, g \, \beta^2 \, T^2 \, . \qquad (7)</math> | ||

| − | + | Using for the coefficient <math>A</math> the value <math>A \approx 0.14</math>, reasonable agreement is found with field and laboratory observations. <ref name=H17/> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Related articles== | |

| + | : [[Swash zone dynamics]] | ||

| + | : [[Wave set-up]] | ||

| + | : [[Swash]] | ||

| + | : [[Waves on a sloping bed]] | ||

| + | : [[Tsunami]] | ||

| + | : [[Breaker index]] | ||

| + | : [[Wave overtopping]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | == | + | {{author |AuthorID=120 |AuthorFullName=Job Dronkers |AuthorName=Dronkers J}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Category:Beaches]] | |

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 10:14, 6 November 2025

Definition of Wave run-up:

Wave run-up is the maximum onshore elevation reached by waves, relative to the shoreline position in the absence of waves.

This is the common definition for Wave run-up, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

Wave run-up on the beach is the sum of wave set-up and swash uprush and must be added to the water level elevation resulting from tides, wind stress, air pressure and other oceanographic processes (Fig. 1). Wave run-up results from the momentum carried by waves when they collapse or surge onto the beach. Short, wind-generated waves turn into uprushing swash bores. Wave run-up is an important phenomenon for assessing the safety of sea dikes or coastal settlements.

Wave run-up refers to waves generated by wind (locally or on the ocean) or waves generated by incidental disturbances of the sea surface such as tsunamis, seiches or ship waves. Wave run-up is usually indicated with the symbol [math]R[/math]. It is often represented by the 2 % exceedance level [math]R_2[/math].

Many empirical formulas for the wave run-up have been derived from laboratory and field data, some of which are reproduced in the paragraph below. Most formulas consider the wave height [math]H[/math], the wavelength [math]L[/math] and the foreshore slope [math]\tan \beta[/math] as most relevant parameters. When comparing with field measurements, a much greater variability (up to about 50%) is generally observed than can be explained by variations in [math]H[/math], [math]L[/math] and [math]\tan \beta[/math].[1] This can likely be (partially) explained by variability in the morphology of the upper shoreface, such as the presence/absence of rip channels, rip head bars, longshore or transverse sand bars. These morphological features seem to be particularly relevant for the infragravity component of the swash uprush. [2]

Contents

Empirical formulas sandy beaches

For regular waves collapsing on the beach, a first order-of-magnitude estimate is given by the empirical formula of Hunt (1959) [3][4][1],

[math]R \sim \eta_u + H \xi , \qquad (1)[/math]

where [math]\eta_u \sim 0.2 H[/math] is the wave set-up, [math]H[/math] is the offshore significant wave height and [math]\xi[/math] is the surf similarity parameter,

[math]\xi = \Large\frac{\beta}{\sqrt{H/L}}\normalsize = T \, \beta \, \Large\sqrt{\frac{g}{2\pi H}}\normalsize , \qquad (2)[/math]

where [math]\tan \beta \approx \beta[/math] is the beach slope and [math]T[/math] is the peak wave period. The offshore wavelength [math]L[/math] is given by [math]L = g T^2/(2 \pi)[/math], assuming that [math]L / (2 \pi) [/math] is smaller than the local depth [math]h[/math]. The horizontal wave incursion is approximately given by [math]R / \beta[/math].

The maximum run-up depends on the mean water level at the shoreline. This water level is increased by wave-induced setup [math]\eta_0[/math], see Wave set-up. The following empirical relationship has been derived for the sum of maximum wave setup and swash runup[5]:

[math] R \approx 0.73 \; \beta \; \sqrt{HL} . \qquad (3)[/math]

Many empirical formulas have been proposed for the run-up. A popular formula for the run-up [math] R_2[/math] exceeded by only 2 % of the waves for given [math]H, L[/math] has been developed by Stockdon et al. (2006[5]), based on a large dataset:

[math] R_2 = 1.1 \; (\eta_u + 0.5 \sqrt{S_w^2 + S_{ig}^2} \, ) , \qquad \xi \ge 0.3 , \qquad R_2= 0.043 \; \sqrt{HL} , \qquad \xi \lt 0.3 , \qquad (4) [/math]

where [math]\eta_u = 0.35 H \xi[/math] is the wave set-up, [math]S_w=0.75 H \xi[/math] is the swash uprush related to incident waves and [math]S_{ig}=0.06 \sqrt{HL}[/math] is the additional uprush related to infragravity waves. The factor 1.1 takes into account the non-Gaussian distribution of run-up events.

An empirical expression taking the medium sediment grain size [math]d_{50}[/math] [m] into account is[3][6],

[math]R = 0.4 \beta \,T \, \sqrt{gH} \, \exp(-10 \, d_{50}^{0.55}) \, . \qquad (5) [/math]

This formula is less suitable for dissipative beaches, where swash is dominated by infragravity waves. In this case a dependence on the square root of the beach (swash) slope should be preferred, e.g. [math]\,\eta_u = (0.2-0.3) \, \sqrt{\beta \, H_s \, L} \,[/math] [7][8]. Other studies find that run-up dominated by infragravity waves is generally small and increases with increasing wave height (approximately linear dependence[9][10]).

From an inventory of run-up formulas by Gomes da Silva et al. (2020[11]), it appears that for steep beaches ([math] \beta \gt 0.1[/math]) the run-up increases with increasing beach slope (approximately linear dependance[12]), while for gently sloping dissipative beaches ([math] \beta \lt 0.1[/math]) the dependence on beach slope is weak or absent[12][5]. Field observations[13] and numerical models[14] point to a dependence of infragravity swash on the frequency spread and the directional spread of incident waves. The largest infragravity swash has been observed for incident waves with a small directional spread and a large frequency spread.

Run-up on mixed sand-cobble beaches

Mixed sand-cobble beaches have a sandy upper shoreface and lower beach with typical slopes of 0.01-0.05 that dissipate most shortwave energy. The upper beach, in contrast, has a steep berm with a slope of 0.1-0.25 and is composed of coarse sediment. Due to cobble roughness, swash infiltration and reflection, backwash velocities are small. These beaches therefore tend to be stable, especially since cobble berms can also dynamically adjust to wave impacts (see Stability of rubble mound breakwaters and shore revetments). Sandy beach run-up formulas overpredict run-up on mixed beaches by ignoring the effects of increased percolation, reflection and roughness. Run-up observations on mixed sand-cobble beaches by Conlin et al. (2025[15]) were best simulated with the empirical expression

[math]R_2 = 1.3 \, (\eta_u + ½ S)\, , \quad \eta_u = 0.92 \, \beta \, H_s^{0.7}\, L^{0.3} \, , \quad S = 1.28 + 3 \, \beta \, H_s \, . \qquad (6)[/math]

Accuracy of run-up estimates

The accuracy (root-mean-square deviation) of run-up predictions using empirical formulas such as (1), (3) or (4) is usually not better than [math]0.25 \, R[/math].[1] The general applicability of empirical formulas for run-up prediction based on simple parametric representations of beach and shoreface is limited due to the influence of the more detailed characteristics of the local beach and shoreface bathymetry (e.g., beach permeability and groundwater level, curvature of the beach profile, crescentic bars, or swash acceleration along the horn of a beach cusp embayment[16]). The tide level may influence the wave run-up due to wave breaking on nearshore sandbars.[17] The applicability of empirical formulas for the wave set-up, which is a substantial component of the run-up, is limited for similar reasons. Accurate estimates of the wave run-up require in-situ observations or detailed numerical models. A more detailed discussion of wave run-up and backwash is given in the articles Swash and Swash zone dynamics. An analytical model estimate of the runup of monochromatic non-broken waves on a uniform sloping beach is discussed in the article Waves on a sloping bed.

Run-up saturation

The empirical formulas suggest that the run-up is an ever increasing function of the incident wave height. Field and laboratory observations show that this is not the case[18][19]. Several processes limit the uprush on the beach when incident waves are very high: breaking of short waves in the surf zone (leading to surf zone saturation), breaking of infragravity waves on the beach face and collision of the uprushing swash bore with the backwash of the preceding swash bore. More details can be found in the articles Swash, Swash zone dynamics and Breaker index. The greatest wave run-up occurs for the highest waves that do not break, which are generally waves in the lower part of the wave frequency spectrum (long-period waves). Theoretical formulas for run-up saturation (for monochromatic frictionless waves, see the articles Waves on a sloping bed, Swash) have the form

[math]R \lt R_s = A \, g \, \beta^2 \, T^2 \, . \qquad (7)[/math]

Using for the coefficient [math]A[/math] the value [math]A \approx 0.14[/math], reasonable agreement is found with field and laboratory observations. [19]

Related articles

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Atkinson, A.L., Power, H.E., Moura, T., Hammond, T., Callaghan, D.P. and Baldock, T.E. 2017. Assessment of runup predictions by empirical models on non-truncated beaches on the south-east Australian coast. Coast. Eng. 119: 15–31

- ↑ Gracia-Barrera, A.D., Ruiz de Alegría-Arzaburu, A., Coco, G., Simarro, G. and Calvete, D. 2025. Alongshore runup variability across contrasting beach states: Insights from field observations. Geomorphology 473, 109640

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hunt, I.A. 1959. Design of seawalls and breakwaters. J. Waterw. Harbors Division ASCE 85: 123–152

- ↑ Holman, R.A. and Sallenger, A.H. 1985. Setup and swash on a natural beach. J. Geophys. Res. 90: 945–953

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Stockdon, H.F., Holman, R.A., Howd, P.A. and Sallenger, A.H. 2006. Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coast. Eng. 53: 573–588

- ↑ Sunamura,T. 2004. A predictive relationship for the spacing of beach cusps in nature. Coastal Engineering 51: 697-711

- ↑ Medellín, G., Brinkkemper, J.A., Torres-Freyermuth, A., Appendini, C.M., Mendoza, E.T. and Salles, P. 2016. Run-up parameterization and beach vulnerability assessment on a barrier island: a downscaling approach. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 16: 167–180

- ↑ Gomes da Silva, P., Medina, R., González, M. and Garnier, R. 2018. Infragravity swash parameterization on beaches: the role of the profile shape and the morphodynamic beach state. Coast. Eng. 136: 41–55

- ↑ Ruessink, B.G., Kleinhans, M.G. and Van Den Beukel, P.G.L. 1998. Observations of swash under highly dissipative conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 103: 3111–3118

- ↑ Ruggiero, P., Holman, R. A. and Beach, R. A. 2004. Wave run-up on a high-energy dissipative beach. J. Geophys. Res. 109, C06025, doi:10.1029/2003JC002160

- ↑ Gomes da Silva, P., Coco, G., Garnier, R. and Klein, A.H.F. 2020. On the prediction of runup, setup and swash on beaches. Earth-Science Reviews 204, 103148

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Nielsen, P. and Hanslow, D.J. 1991. Wave runup distributions on natural beaches. J. Coast. Res. 7: 1139–1152

- ↑ Matsuba, Y. and Shimozono, T. 2021. Analysis of the contributing factors to infragravity swash based on long-term observations. Coastal Engineering 169, 103957

- ↑ Guza, R.T. and Feddersen, F. 2012. Effect of wave frequency and directional spread on shoreline runup. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39: 1–5

- ↑ Conlin, M.P., Wilson,G., Bond, H., Ardag, G. and Arnowil, C. 2025. Predicting wave runup on composite beaches. Coastal Engineering 199, 104743

- ↑ Kim, L.N., Brodie, K.L., Cohn, N.T., Giddings, S.N. and Merrifield, M. 2023. Observations of beach change and runup, and the performance of empirical runup parameterizations during large storm events. Coastal Engineering 184, 104357

- ↑ Guedes, R.M.C., Bryan, K.R., Coco, G. and Holman, R.A. 2011. The effects of tides on swash statistics on an intermediate beach. J. Geophys. Res. 116, C04008

- ↑ Guza, R.T., Thornton, E.B. and Holman, R.A. 1984. Swash on steep and shallow beaches. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference Coastal Engineering, ASCE, 1, pp. 708 – 723

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Hughes, M.G., Baldock, T.E. and Aagaard, T. 2017. Swash saturation: is it universal and do we have an appropriate model? Coastal Dynamics Conf. 2017, Paper No.108, pp. 192-203

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|