Wave overtopping

Definition of Wave overtopping:

Wave overtopping refers to the average quantity of water that is discharged per linear meter by waves over a protection structure (e.g. breakwater, dike) whose crest is higher than the still water level (SWL).

This is the common definition for Wave overtopping, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

|

|

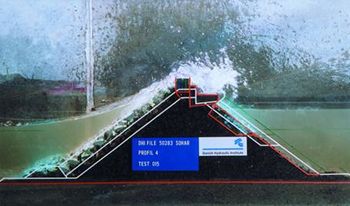

| Fig. 1a. Wave-overtopping of a breakwater in a flume test. | Fig. 1b. Wave-overtopping of a breakwater in nature. |

Contents

Sloping structures

Photographs of wave overtopping from laboratory and field are shown in Fig. 1, while Fig. 2 presents a schematic representation with the relevant definitions. During wave overtopping, two key processes occur: wave run-up on the structure and partial transmission of wave energy across the crest. Wave overtopping is a highly intermittent process in time, space, and volume, and does not result in a continuous discharge over the crest of the structure. Only the highest waves may convey a large volume of water over the crest within a short time interval—often less than a single wave period—whereas smaller waves may not cause overtopping at all.

The wave height at the toe of the structure is known

An empirical formula for the average water discharge [math]q[/math] per linear meter by waves over a protection structure is given in the EurOtop manual[1]

[math]\Large\frac{q}{\sqrt{gH_{m0}^3}}\normalsize \equiv q^* = 0.09 \exp(-\large\frac{1.5 R_c}{\gamma_f H_{m0}}\normalsize) \, , \qquad (1)[/math]

for perpendicular wave incidence. Since overtopping rates of more than a factor 10 higher were observed in several experiments, a revised formula was developed by Eldrup et al. (2022[2]). The general form of the wave overtopping discharge is

[math]q^* = a \, \exp\Big[ \big(-b \large\frac{R_c}{H_{m0}}\normalsize \big)^c \Big] \, , \qquad (2)[/math]

where the coefficients [math]a, b, c[/math] depend on (see Fig. 2):

- The spectral wave height at the toe of the structure [math]H \equiv H_{m0}[/math] (approximately equal to the significant wave height [math]H_s[/math], see Statistical description of wave parameters)

- The spectral wave energy period [math]T \equiv T_{m-1,0}[/math] at the toe of the structure

- The wave steepness [math]s = H/L[/math], where [math]L=g T^2 / (2 \pi)[/math] is the wavelength

- The wave incidence angle [math]\theta[/math]

- The water depth [math]h_{toe}[/math] at the toe of the structure

- The breakwater wave run-up [math]R_2[/math] exceeded by only 2 % of the waves; [math]R_2/ H[/math] depends on the roughness (and permeability) reduction factor [math]\gamma_f[/math], the surf similarity parameter [math]\xi[/math] and the wave obliqueness,

- The freeboard [math]R_c[/math] (the structure crest level relative to the still water level SWL);

- The seabed (or foreshore) slope [math]m[/math]

- The front slope of the structure [math]\tan \alpha[/math]

- The crest width of the structure [math]G_c[/math]

- The surf similarity parameter (Iribarren number) [math]\xi = \tan \alpha / \sqrt{s}[/math]

- The roughness and permeability reduction factor [math]\gamma_f[/math] that accounts for the roughness and percolation of structures’ slope. For smooth revetments [math]\gamma_f =1[/math]. Usual values for rubble mound structures are in the range [math]\gamma_f \approx 1 – 0.7 \, (D_{n50}/H)^{0.1} \sim 0.4 – 0.6[/math], where [math]D_{n50}[/math] is the median diameter of the armor stones.

Further adjustments to the friction factor [math]\gamma_f[/math] may be needed to account for the presence of a crest wall and the presence of a berm.

Empirical formulas for overtopping discharges are derived from flume experiments that simulate typical design values in the range: [math]H \sim[/math]2-5 m, [math]T \sim[/math]8-15 s, [math]h_{toe}/H \sim [/math]1-10, [math]R_2/H \sim [/math]2-6, [math]R_c/H \sim [/math]0.5-2.5, [math]G_c/H \sim [/math]1-5, [math]\tan \alpha \sim [/math]0.25-0.6, [math]m \sim[/math]0.005-0.05, [math]\xi \sim [/math]1.5-8.

Wave overtopping experiments by van Gent et al. (2022[3]) are best represented by formula (2) with

[math]a = \dfrac{0.0016}{s} \, , \quad b = \dfrac{2.4}{\gamma_f \, \gamma_{\theta}} \, , \quad c=1 \, . \qquad (3)[/math].

Here is [math]s[/math] the wave steepness, [math]\gamma_f[/math] the roughness and permeability factor and [math]\gamma_{\theta}[/math] a reduction factor that accounts for oblique wave incidence. The value of [math]\gamma_{\theta}[/math] decreases from [math]\gamma_{\theta}=1[/math] for normal wave incidence ([math]\theta=0[/math]) to [math]\gamma_{\theta} \sim 0.85-0.95[/math] for [math]\theta=30°[/math] and [math]\gamma_{\theta} \sim 0.7-0.85[/math] for [math]\theta=60°[/math]. [4]

Etemad-Shahidi et al. (2022)[5] proposed a formula for the mean overtopping discharge of rubble mound breakwaters by surging (non-breaking) waves:

[math]q^* = (1.22 \pm 0.13) 10^{-4} \, \exp \big[ (3.5 \pm 0.13) \large\frac{R_2 -R_c}{H}\normalsize – (0.64 \pm 0.07) \large\frac{G_c}{H}\normalsize \big] . \qquad (4)[/math]

The standard deviation of observational data with respect to this formula is about a factor 3. This uncertainty is mainly related to estimating the wave run-up. The EurOtop manual[1] proposes for approximately normal wave incidence:

[math]R_2 = 1.65 \, \gamma_f \, H \, \xi \;[/math], with a maximum of [math]\gamma_{sf} \, H \, (4 - 1.5 \, \xi^{-1/2})[/math]. The friction factor [math]\gamma_{sf}[/math] for surging waves is estimated as [math]\gamma_{sf} = \gamma_f + 0.12 \, (1-\gamma_f)(\xi-1.8)[/math] with a minimum value equal to [math]\gamma_f[/math].

The formulas (1,4) overpredict the mean wave overtopping in the shallow surf zone where [math]h_{toe}/H \lt 0.5[/math] [6]. For this case, de Ridder et al. (2024[7]) propose the formula

[math]q = \sqrt{g H^3_{HF}} \; q^* \, , \quad q^*= 0.44 \exp \Big[ -8.75 \, s^{0.33}_{HF} \, \large\frac{R_c \, – \, 0.38 \, H_{LF}}{\gamma_f H}\normalsize \Big] , \qquad (5)[/math]

where the subscript [math]HF[/math] refers to the contribution of the high-frequency waves in the shallow-water wave spectrum ([math]s_{HF}[/math] is the corresponding wave steepness) and the subscript [math]LF[/math] refers to the contribution of the low-frequency waves. The mean overtopping discharge is the average over many individual waves. Some waves can produce overtopping volumes much larger than the average. The largest overtopping volumes of rubble-mound structures in shallow water occur for short waves riding on the crest of low-frequency (infragravity) waves. Flume experiments[8] show that the overtopping volumes of individual waves follow approximately a log-normal distribution. Empirical formulas for the 2% largest overtopping volumes [math]V_2[/math] and related overtopping heights [math]h_2[/math] and overtopping velocities [math]u_2[/math] are

[math]V_2= 5.56 \, H^2 \exp \Big( -9.94 \dfrac{R_c \, s^{0.57}_{HF}}{\gamma_f H} \Big) \, , \quad h_2= 0.63 \, H \exp \Big( -4.88 \dfrac{R_c \, s^{0.5}_{HF}}{\gamma_f H} \Big) \, , \quad u_2= 1.26 \sqrt{gh} \Big( \dfrac{R_c \, s^{-0.24}_{HF}}{\gamma_f H} \Big)^{-1.05} \, . \qquad (6)[/math]

Astorga-Moar and Baldock (2023[9]) conducted a laboratory investigation of wave overtopping of a beach with constant slope [math]\tan \alpha[/math] and berm height [math]R_c[/math] above still water, fronted by a low reef or shore platform. They found the following relationship of the mean wave overtopping discharge [math]q^*[/math] with the 2% wave run-up [math]R_2[/math], the spectral wave height [math]H[/math] at the toe of the beach and the peak wave period [math]T_p[/math],

[math]q^* = 0.015 \, \xi_p \, \Big(\large\frac{R_2-R_c}{R_2}\normalsize \Big)^2 \, , \quad \xi_p = T_p \, \tan \alpha \, \sqrt{\large\frac{g}{2 \pi H}} \, .\qquad (7)[/math]

Only the deep-water wave height is known

The wave height at the toe of the structure depends on the bed profile and is often not well known – particularly when a beach is present in front of the structure. During a storm the beach profile evolves, typically by lowering of the beach directly in front of the structure and the formation of a nearshore bar farther offshore in the submerged profile. For a given offshore wave height, lowering of the beach in front of the structure leads to increased wave overtopping volumes[10]. In contrast, the presence of a nearshore bar promotes breaking of the largest incident waves and therefore reduces the overtopping volumes[11]

A numerical model study by Lashley et al. (2020[12]) showed that the influence of the foreshore is insignificant if the deep-water significant wave height [math]H_{\infty} \equiv H_{m0,\infty}[/math] is smaller than the water depth [math]h_{toe}[/math] at the toe of the structure. In the case of a shallow foreshore ([math]h_{toe}/H_{\infty} \lt 1[/math]), Lashley et al. (2021[13]) proposed the following formula for the dimensionless overtopping rate [math]q^*[/math],

[math]q^*=a \, \exp\Big(-b \dfrac{R_c}{H_{\infty}} + c \dfrac{h_{toe}}{H_{\infty}} \Big) \, , \quad a=1.9 \, s^{1.15} ,\; b=7.4 \, m^{-0.25} s^{0.6} (\tan \alpha)^{-0.6},\; c=0.7 \, m^{0.8} s^{-0.8}. \qquad (8)[/math]

For very shallow foreshores ([math]h_{toe}/H_{\infty} \lt 0.1[/math]), [math]\quad a=1.35 \, m^{0.35} s^{0.85} ,\; b=3.75 \, m^{-0.7} s^{0.7} (\tan \alpha)^{-0.6},\; c=0.2 \, m^{-1.3} s^{0.35} \, . \qquad (9)[/math]

These formulas must be applied with caution, because of foreshore evolution during storms.

Vertical walls

From numerical simulations validated with flume experiments, Tuozzo et al. (2024[14]) found that the overtopping discharge of a vertical seawall in shallow water depends crucially on the upper tail [math]\zeta_{1/4}[/math] of the wave elevation distribution [math]f(\zeta)[/math] at the toe of the seawall:

[math]\zeta_{1/4} = 4 \int_{\zeta 75}^{\infty} \zeta f(\zeta) d \zeta ,[/math]

where [math]\zeta[/math] is the wave elevation at the toe of the seawall and [math]\zeta 75[/math] is the 75th percentile. For linear (symmetric) waves this can be approximated by [math]\zeta_{1/4} = \mu + 0.32 \sqrt{H} [/math], where [math]\mu[/math] is the mean elevation.

The proposed formula for the overtopping discharge is

[math]q = g \, h_{toe} \, T_{\infty} \, m^{p_1} \, q^*(z) \, , \quad q^*(z) = min\big[ 0.0107 \, z^{-1.49}\, ; \, 0.068 \, z^{-3.04} \big] \, , \quad z=\Large\frac{p_2 R_c}{\zeta_{1/4}}\normalsize \, , \qquad (10)[/math]

where [math]p_1=\big[ 2+100 \, \exp(- 10 \gamma_{\infty}) \big]^{-1}\, , \quad p_2 = max \Big[1\, ; \, \Large\frac{1}{\gamma_{\infty}}\normalsize \tanh\big(\large\frac{10 \pi s_{\infty}}{\gamma_{\infty}}\normalsize \big) \Big] \, , \quad \gamma_{\infty} = \Large\frac{H_{\infty}}{h_{toe}}\normalsize . [/math]

The subscript [math]\infty[/math] refers to deep water conditions and [math]s_{\infty}[/math] is the deep water wave steepness.

Onshore wind increases the overtopping discharge[15]. Vegetation (e.g. mangroves, seagrass) in front of the seawall reduces wave overtopping, see Nature-based shore protection.

The following formula has been derived for shallow foreshores ([math]h_{toe}/H_{\infty} \lt 1[/math]),[13]

[math]q^*=a \, \exp\Big(-b \dfrac{R_c}{H_{\infty}} + c \dfrac{h_{toe}}{H_{\infty}} \Big) \, , \quad a=0.9 \, m^{2.05} s^{-0.2} ,\; b=5.1 \, m^{-0.15} s^{0.25} ,\; c=0.7 \, m^{-0.55} s^{0.1} \, , \qquad (11)[/math]

and for very shallow foreshores ([math]h_{toe}/H_{\infty} \lt 0.1[/math]): [math] \quad a=0.09 \, m^{2.35} s^{-1.25} ,\; b=5.4 \, m^{-0.45} s^{0.3} ,\; c=0.75 \, m^{-0.6} s^{0.5} \, . \qquad (12)[/math]

These formulas should be applied with caution because storm events can significantly alter the foreshore profile.

Related articles

- Stability of rubble mound breakwaters and shore revetments

- Wave set-up and wave transmission by low-crested breakwaters

- Wave run-up

- Overtopping resistant dikes

- Detached breakwaters

- Modelling coastal hydrodynamics

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 EurOtop, 2018. Manual on wave overtopping of sea defences and related structures. An overtopping manual largely based on European research, but for worldwide application. Van der Meer, J.W., Allsop, N.W.H., Bruce, T., De Rouck, J., Kortenhaus, A., Pullen, T., Schüttrumpf, H., Troch, P. and Zanuttigh, B., www.overtopping-manual.com

- ↑ Eldrup, M.R., Andersen, T.L., Van Doorslaer, K. and Van der Meer, J. 2022. Improved guidance on roughness and crest width in overtopping of rubble mound structures along EurOtop. Coastal Engineering 176, 104152

- ↑ van Gent, M.R.A., Wolter, G. and Capel, A. 2022. Wave overtopping discharges at rubble mound breakwaters including effects of a crest wall and a berm. Coastal Engineering 176, 104151

- ↑ van Gent, M.R.A. 2021. Influence of oblique wave attack on wave overtopping at caisson breakwaters with sea and swell conditions. Coastal Engineering 164, 103834

- ↑ Etemad-Shahidi, A., Koosheh, A. and Van Gent, M.R.A. 2022. On the mean overtopping rate of rubble mound structures. Coastal Engineering 177, 104150

- ↑ Tarakcioglu, G.O., Kisacik, D., Gruwez, V. and Troch, P. 2023. Wave Overtopping at Sea Dikes on Shallow Foreshores: A Review, an Evaluation, and Remaining Challenges. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 638

- ↑ de Ridder, M.P., van Kester, D.C.P., van Bentem, R., Teng, D.Y.Y. and van Gent, M.R.A. 2024. Wave overtopping discharges at rubble mound structures in shallow water. Coastal Engineering 194, 104626

- ↑ de Ridder, M.P., van Kester, D.C.P., Mares-Nasarre, P. and van Gent, M.R.A. 2025. Individual overtopping volumes, water layer thickness and front velocities at rubble mound breakwaters with a smooth crest in shallow water. Coastal Engineering 198, 104701

- ↑ Astorga-Moar, A. and Baldock, T.E. 2023. Assessment of wave overtopping models for fringing reef fronted beaches. Coastal Engineering 186, 104395

- ↑ Briganti, R., Musumeci, R.E., van der Meer, J., Romano, A., Stancanelli, L.M., Kudella, M., Akbar, R., Mukhdiar, R., Altomare, C., Suzuki, T., De Girolamo, P., Besio, G., Dodd, N., Zhu, F. and Schimmels, S. 2022. Wave overtopping at near-vertical seawalls: influence of foreshore evolution during storms. Ocean Eng. 261, 112024

- ↑ Altomare, C., Marzeddu, A. and Gironella, X. 2026. Storm-sequence control of beach evolution and overtopping at vertical promenade defences. Ocean Engineering 347, 123789

- ↑ Lashley, C. H., Bricker, J. D., van der Meer, J., Altomare, C. and T. Suzuki, T. 2020. Relative magnitude of infragravity waves at coastal dikes with shallow foreshores: A prediction tool. J. Waterw. Port Coastal Ocean Eng. 146, 04020034

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lashley, C.H., van der Meer, J., Bricker, J.D., Altomare, C., Suzuki, T. and Hirayama, K. 2021. Formulating wave overtopping at vertical and sloping structures with shallow fore-shores using deep-water wave characteristics. J. Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Eng. 147, 04021036

- ↑ Tuozzo, S., Calabrese, M. and Buccino, M. 2024. An overtopping formula for shallow water vertical seawalls by SWASH. Applied Ocean Research 148, 104009

- ↑ Aoki, Y., Sasaki, K., Nakamura, R., Ishibashi, K., Yamamoto, K., Inagaki, N. and Shibayama, T. 2024. Laboratory study on effect of vegetation in reducing wave overtopping under wind effect. Ocean Engineering 311, 118984

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|