Salinization adaptation and freshwater supply for agriculture in the Dutch Delta

This article describes a case study, which provides an example of structuring problems in order to improve stakeholder dialogue. It uses the Delta area of the Netherlands and in particular focuses on issues surrounding the restoration of estuarine dynamics and sustainable supply of freshwater for agriculture.

The more general issue of saline groundwater in coastal zones, including causes and solutions, is dealt with in the article Groundwater management in low-lying coastal zones.

Contents

Introduction

The delta of the rivers Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt, located in the Southwest of the Netherlands, is unique for its large water systems surrounded by dikes and dams to protect the hinterland against flooding. With the construction of a storm surge barrier in the Eastern Scheldt in 1986, the Dutch Delta Works safety restoration programs were completed. The construction of the Delta Works made the Southwest of the Netherlands safer, more accessible and several newly created freshwater basins provided opportunities for drinking water supply and agriculture. The hydraulic engineering projects have been executed allowing ecological concerns to be taken into account to the best available knowledge. As a result the economic development of the Delta region was highly stimulated. Safety against flooding is nowadays on a high standard, nonetheless sea level rise and climate change require ongoing attention and investments.

While some environmental drawbacks were expected at the time, the Delta currently faces many ecological problems and possible solutions require high investments for mitigation or restoration. These problems are related to the disappearance of the characteristic freshwater-saltwater transitions and estuarine dynamics. One of these ecological problems is the excessive growth of blue-green algae in the Volkerak-Zoom lake (VZ-lake). The Dutch Government regards the re-establishment of estuarine dynamics in the Delta an important solution to restore the ecological quality (whilst preserving safety against flooding and transportation possibilities) (Ministeries van VROM et al. 2004[1]). This policy, together with the perspectives of sea level rise, lower river flows and increasing risk of too dry summers periods result in the common finding that salinization of the Delta is becoming a major issue for agriculture.

The question is thus “How to combine the restoration of estuarine dynamics with freshwater supply for agriculture in a sustainable way?”. The national government asked the Delta Provinces to start a fundamental discussion with different stakeholders on this issue. Because problems are very context-specific, it was decided to have consecutive dialogues in different areas of the Delta. The first project is a pilot-project about safeguarding freshwater supply for agriculture on the islands Tholen and St. Philipsland. Farmers on these islands extract from the VZ-lake freshwater for agricultural purposes. This paper describes the case study concerning this pilot-project executed in 2007.

Case study analysis

Methodology

Objective of the case study is to get insight in problem structuring by analyzing the role of interaction, problem perceptions and knowledge. Problem structuring is an interactive process in which all relevant stakeholders develop a joint formulation of the problem and its solutions (Hisschemöller 1993[2]; Rosenhead 1989[3]). Ideally, this formulation is based on ‘negotiated knowledge’, i.e. knowledge which is agreed upon and valid (see e.g. De Bruijn et al. 2002[4]; Van de Riet 2003[5]). In the case study, problem structuring is analyzed along three tracks:

- Participatory process: How did the interactive process develop? E.g. which actors were involved, what was the scope of the process and which interactive activities were organized?

- Perceptions: How are stakeholders’ problem perceptions developing? This analysis includes the analysis of normative elements (interests, objectives, criteria) and cognitive elements (view of the world, the problem, chances and bottlenecks).

- Knowledge: How is the content of the knowledge base developing? This analysis includes the role of different actors in the production of knowledge.

These three tracks are analysed against the background and history of the interactive process and its social and natural environment. For the analysis different methods and sources are used, such as observations during the interactive process, analysis of research reports and project documents, interview reports, news articles and internet sources and interviews with process managers.

The participatory process

Objective of the pilot-project is “to develop a shared insight and agreement about the most desirable direction for solutions or development” with respect to freshwater supply for agriculture given the possible freshwater situations in the Dutch Delta. To realize this objective, the responsible government body (the Delta Council) decided to start a participatory process. Participating stakeholders are local farmers; representatives from the agricultural interest organization; agricultural business; national, regional and local nature societies; local and regional water managers; local and provincial public servants and delegates. The process design consists of several converging and diverging phases: analysis of chances and bottlenecks, the generation of solutions, and the adaptation of possible solutions. Every phase starts with a broad scope after which selection takes place. A broad scope is characteristic for the discussion, no problem formulations are excluded. The result of the participatory process goes beyond expectations, all stakeholders agreed upon one direction for solutions given the prior condition of a saline Volkerak-zoom lake. This solution includes the safeguarding of freshwater supply for agriculture by means of a pipeline supplying water from a river upstream, after which steps can be taken to re-establish estuarine dynamics.

Perceptions

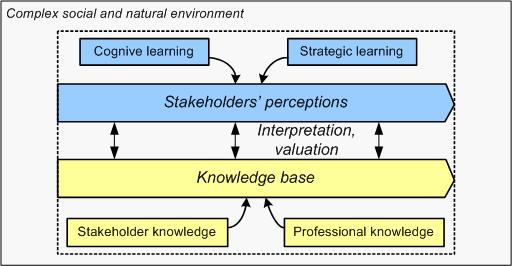

At the outset of the discussion, stakeholders’ perceptions diverge and people do not understand each other. The exchange of perceptions (chances, bottlenecks, possible solutions) during several workshops and an excursion through the area enhanced convergence of perceptions and mutual understanding. For every participants one of more elements of their problem formulation changed during the process. But, because interests and objectives diverge, they do not become identical. Still, stakeholders reach an agreement about the most preferable solution. According to Koppenjan and Klijn (2004[6]) cognitive and strategic learning contribute directly to the outcomes of participatory policy processes. Cognitive learning refers to “the increased knowledge and insight about the nature of the problem, possible solutions, and their consequences” (p. 125[6]). Strategic learning involves “parties growing consciences of each others involvement and their mutual dependencies” (p. 127[6]). How these learning processes develop and their impact relates to the background of participants. Especially for representatives from the public sector it is difficult to change objectives, because they are incorporated in an organization and bound to policy and promises.

Knowledge

At the outset of the process, the process managers present a note concerning the process to participants which summarizes existing information and research. This note aims to provide a starting-point for the discussion. The note presents findings from previous research, but also bottlenecks experienced by stakeholders and their divergent views on sustainability (see Reijs 2006a[7]). The most relevant research report goes into the future of agriculture in relation to freshwater supply (Stuyt et al. 2006[8]). The findings of this report appear to conflict with the experiences and expectations from participating farmers. The development of possible solutions with representatives from the agricultural sector creates a substantive breakthrough. In the same period, the process managers also consult the nature sector and government organizations. During these meetings stakeholders are enhanced to contribute with their own knowledge and experiences. Consequently, the content of the conclusions in the closing report are a mix of knowledge from professional experts (laid down in research reports) and stakeholder knowledge (based on their experiences). Although some reservations are made, the created knowledge base is agreed upon by all participants of the process. A reservation is made by the government, asking for an additional societal costs-benefits analysis (although costs and benefits have been calculated). On behalf of the nature sector, figures are accompanied by the remark that they need to be verified by professional experts (see Reijs 2006b[9]).

Conclusions

Aim of this case study research is to get insight in problem structuring. This section presents some conclusions on problem structuring. These conclusions are based on the presented case study, our experiences with another case study project (an interactive process on sediment management) and a literature review on problem structuring.

Problem structuring is not a clear-cut, isolated process. A participatory interactive process does not start with blank perceptions or a blank knowledge base. Perceptions and knowledge are constantly developing before, during and after the participatory process. Besides this, developments within the social and natural environment also influence a participatory process (Koppenjan and Klijn 2004[6]). The dynamics of participatory processes ask for adaptive process management (Edelenbos and Klijn 2006[10]). The case study supports the idea that process management should be adaptive. Moreover, the case study shows the importance of an open process approach, so that the divergent perceptions of all participants are included.

The case study shows that stakeholders’ perceptions adjust because stakeholders learn cognitively and strategically. The case study also supports the idea that to create context-specific knowledge, stakeholder knowledge and knowledge from professional experts are useful sources of knowledge (Eshuis and Stuiver 2005[11]). An advantage of using stakeholder knowledge is that it contributes to reaching an agreement, since stakeholders are more likely to accept information if they have been involved in the production (De Bruijn et al. 2002[4]); Eshuis and Stuiver 2005[11]). However, not all stakeholders (especially government partners not) confirm that although stakeholder knowledge is different from knowledge from professional experts, that it is just as valuable (Nowotny 2003[12]; Rinaudo and Garin 2005[13]). In the case study, the connection of different types of knowledge was taken care of by process managers. Thus, it is not necessary to have a face-to-face dialogue between professional experts and stakeholders if process managers can take care of this.

Related articles

The case study is presented before in: De Kruijf, J. (2007). Problem structuring in interactive decision-making processes: How interaction, problem perceptions and knowledge contribute to a joint formulation of a problem and its solutions, Master's thesis, University of Twente, Enschede. This report is available as TNO-report, ref. nr 2007-I&R-065-KFJ-PEM.

References

- ↑ Ministeries van VROM, LNV, VenW , and EZ. (2004). Nota Ruimte - Ruimte voor ontwikkeling / National Spatial Strategy

- ↑ Hisschemöller, M. J. (1993). De democratie van problemen : de relatie tussen de inhoud van beleidsproblemen en methoden van politieke besluitvorming, PhD thesis, Amsterdam : VU Uitgeverij

- ↑ Rosenhead, J. (1989). Rational analysis for a problematic world : problem structuring methods for complexity, uncertainty and conflict, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 De Bruijn, H., Ten Heuvelhof, E. F., and In 't Veld, R. J. (2002). Process management: why project management fails in complex decision making processes, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

- ↑ Van de Riet, A. W. T. (2003). Policy analysis in multi-actor policy settings : navigating between negotiated nonsense and superfluous knowledge. PhD thesis, Technische Universiteit Delft, Delft : Eburon Publishers

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Koppenjan, J. F. M., and Klijn, E. (2004). Managing uncertainties in networks : a network approach to problem solving and decision making Routledge, London [etc.]

- ↑ Reijs, T. A. M. (2006a). Informatie ten behoeve van fundamentele discussie zoetwatersituatie ZW-Delta: Pilot Tholen/St. Philipsland. TNO Bouw en Ondergrond, Innovatie en Ruimte, Delft

- ↑ Stuyt, L. C. P. M., Bakel, P. J. T. V., Kroes, J. G., Bos, E. J., Elst, M. V. d., Pronk, B., Rijk, P. J., Clevering, O. A., Dekking, A. J. G., Voort, M. P. J. V. d., Wolf, M. D., and Brandenburg, W. A. (2006). Transitie en toekomst van de Deltalandbouw; indicatoren voor de ontwikkeling van de land- en tuinbouw in de Zuidwestelijke Delta van Nederland. Alterra, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- ↑ Reijs, T. A. M. (2006b). Verslag en resultaten van de brede discussie zoetwatersituatie voor de landbouw in de Delta: Pilot Tholen & St. Philipsland. TNO Bouw en ondergrond, Innovatie en Ruimte, Delft

- ↑ Edelenbos, J., and Klijn, E. H. (2006). Managing stakeholder involvement in decision making: A comparative analysis of six interactive processes in the Netherlands. Journal Of Public Administration Research And Theory, 16(3), 417-446

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Eshuis, J., and Stuiver, M. (2005). Learning in context through conflict and alignment: Farmers and scientists in search of sustainable agriculture. Agriculture And Human Values, 22(2), 137-148

- ↑ Nowotny, H. (2003). Democratising expertise and socially robust knowledge. Science and Public Policy, 30(3), 151

- ↑ Rinaudo, J. D., and Garin, P. (2005). The benefits of combining lay and expert input for water-management planning at the watershed level. Water Policy, 7(3), 279

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|