Proudman resonance and meteo tsunamis

Definition of Meteo tsunamis:

Meteo tsumanis are long ocean surface oscillations generated by intense atmospheric disturbances travelling over the open sea.

This is the common definition for Meteo tsunamis, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

The frequency band of meteo tsunamis waves corresponds to that of seismically generated tsunamis, which explains their naming. They are sometimes also called nonseismic sea-level oscillations at tsunami timescales (NSLOTTs). They are recorded on most continental shelves globally, where strong secondary amplification can occur due to topographic resonance effects[1] (see Harbor resonance). Regionally, meteo tsunamis are known by different local names: rissaga (Spain’s Balearic Islands and New Zealand), abiki (Japan’s Nagasaki Bay), sciga (Adriatic), milghuba (Malta), marrobbio (Sicily), seebär (Baltic Sea)[2]. Amplification by Proudman resonance occurs when an atmospheric disturbance travels over large distances (hundred kilometers or more) at approximately the same speed as the propagation celerity of long ocean waves[3][4][5][6]. Although meteo tsunamis are only a minor component of the overall sea-level oscillations, they can cause sea-level extremes and flooding, especially when combined with higher tides and storm surges, on top of the increased mean sea levels[7]. In some cases they are also capable of generating strong rip currents[8].

Contents

Generation of meteo tsunamis

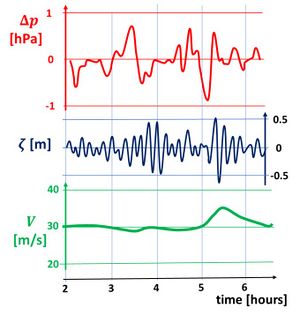

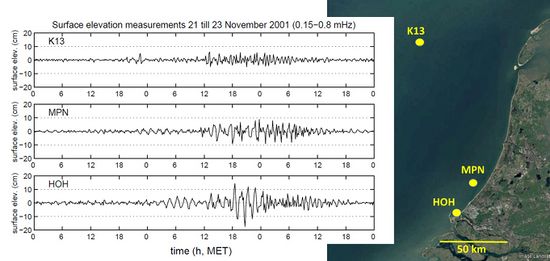

Local atmospheric pressure disturbances above open water generate wave motions at the water surface. Meteo tsunamis are often associated with mid-troposphere jet streams and instability of the troposphere in the zone around 500 hPa[7]. The periods of meteo-induced water waves are typically in the range of a few minutes to a few hours, i.e. intermediate between wind waves and tidal waves. The amplitude of these waves is generally small (typically in the cm range) compared to wind waves and tidal waves. However, in some cases they can be strongly amplified. This occurs when the pressure perturbation advances at a speed comparable to the propagation speed (celerity) of the surface waves in the water body. This amplification is known as Proudman resonance, after the scientist who first demonstrated this phenomenon[3]. When meteo-induced water waves are strongly amplified they are often called meteo tsunamis, because their period is in the same range where tsunamis caused by other phenomena occur, such as submarine earthquakes and landslides – see the article Tsunami. Various atmospheric processes can generate meteo tsunamis, for example frontal passages, gales, squalls, storms, orographic influence and tornados. Examples of meteo tsunamis are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Proudman resonance

Whether the propagation speed [math]V[/math] of an atmospheric pressure disturbance is comparable to the celerity [math]c[/math] of long surface waves depends on the depth of the water body, which can be approximated by [math]c=\sqrt{gh}[/math], where [math]h[/math] is the local water depth and [math]g \approx 9.8 \, m^2 s^{-1}[/math] the gravitational acceleration. In deep ocean water the wave propagation celerity is always much larger (typically in the order of 200 m/s) than the speed of atmospheric pressure disturbances (typically in the order of 10-50 m/s). However, on the continental shelf (depths between 50 and 500 m), the speed can be comparable and Proudman resonance can occur. The mathematical derivation by Proudman is presented in the appendix.

Greenspan resonance

A surface wave induced by an atmospheric pressure perturbation can also be amplified by so-called Greenspan resonance. Greenspan resonance occurs when the atmospheric pressure disturbance travels along a sloping coastal shelf at a speed close to the propagation speed of a edge wave, which is consequently amplified. Different edge waves (modes n =1, 2, 3. ..) travel at speeds [math]c_n \approx (2n-1) \, \beta \, g \, T / (2 \pi)[/math], where [math]\beta[/math] is the shelf slope and [math]T[/math] the edge wave period. Meteo tsunamis have been observed along the south Australian coast which can be explained by Greenspan resonance, as the atmospheric pressure perturbation travels at a speed close to the speed of the first edge wave mode[11].

Harbor seiches

Proudman resonance can amplify the initial meteo-induced water wave by a factor 5-10 if the propagation speeds of the atmospheric disturbance and the water wave are on average about the same[12]. Even in this case the amplitude of the meteo tsunami will seldom exceed a few decimeters. Waves of this amplitude generally do not cause great harm. However, further amplification can occur if the wave period is close to the resonance period of coastal topographic features, such as semi-enclosed bays and basins. Many harbors resonate at wave periods in the same range as the periods of meteo tsunamis, on the order of one minute period for small harbors and on the order of one hour for large harbors (the basic resonance period of an elongate harbor of length [math]L[/math] and depth [math]h[/math] is given by [math]4L/\sqrt{gh}[/math]). If the harbor resonance period and the wave period match, a further wave amplification with a factor 5-10 is possible[13]. Resonant harbor waves are called seiches. For a more detailed discussion of this phenomenon, the reader is referred to the article Harbor resonance. Harbor seiches can cause considerable damage to berthed vessels and harbor infrastructure (Fig. 3).

Not all meteo tsunamis are amplified by Proudman resonance. Strong typhoons can generate long surface oscillations of considerable amplitude when amplified by topographic resonance effects[14].

Appendix: A simple mathematical model of Proudman resonance

The simple model, first described by Proudman[3], considers the following idealised situation:

- Continental shelf of uniform depth [math]h[/math],

- The influence of friction, tide and earth's rotation are neglected.

The pressure disturbance is assumed uniform in [math]y[/math]-direction and moves without deformation in [math]x[/math]-direction with velocity [math]V[/math]. The disturbance is then given by [math]p=p_0 - g \rho f(x-Vt)[/math], where [math]\rho[/math] is water density and [math]g[/math] the gravitational acceleration. The shallow-water equations of motion read

[math]\Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial t}\normalsize + g \Large\frac{\partial \zeta}{\partial x}\normalsize = - \Large\frac{1}{\rho}\frac{\partial p}{\partial x}\normalsize , \quad h\Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial \zeta}{\partial t}\normalsize = 0. \qquad (1)[/math].

Symbols are: [math]\zeta=[/math] sea surface elevation, [math]u=[/math] current velocity and [math]t=[/math] time

Elimination of [math]u[/math] gives the equation [math]\Large\frac{\partial^2 \zeta}{\partial t^2}\normalsize -gh\Large\frac{\partial^2 \zeta}{\partial x^2}\normalsize = -gh\Large\frac{\partial^2 }{\partial x^2} \normalsize f(x-Vt) . \qquad (2)[/math]

The general solution reads

[math]\zeta(x,t)=\zeta^{(1)}(x-ct)+ \zeta^{(2)}(x+ct)+ \zeta^{(3)}(x-Vt), \qquad \zeta^{(3)}=\Large\frac{f}{1-(V/c)^2}\normalsize , \quad c=\sqrt{gh} . \qquad (3)[/math]

The functions [math]\zeta^{(1)}[/math] and [math]\zeta^{(2)}[/math] are determined by the initial conditions [math]\zeta=0, u=0[/math] at [math]t=0[/math]. Evaluation of these conditions yields

[math]\zeta(x,t)=\Large\frac{1}{1-(V/c)^2}\normalsize \Big[ f(x-Vt) - \Large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize (1+\Large\frac{V}{c})\normalsize f(x-ct) - \Large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize (1-\Large\frac{V}{c})\normalsize f(x+ct) \Big] . \qquad (4)[/math]

If the propagation speed of the disturbance is close to the wave celerity, [math]V =c+\Delta c[/math], and if [math] t \Delta c[/math] is much smaller than the spatial scale [math]L[/math] of the pressure field, then the expression of [math]\zeta[/math] can be approximated by

[math]\rho g \zeta(x,t) \approx \large\frac{1}{4}\normalsize \Big( p(x+ct)-p(x-ct) \Big) - \Large\frac{ct}{2}\frac{\partial}{\partial x} \normalsize p(x-ct), \qquad x \le ct . \qquad (5)[/math]

In this case we have Proudman resonance: the amplitude of the meteo-induced wave that propagates at about the same speed as the atmospheric pressure perturbation increases linearly with time. The first term between brackets in the r.h.s. of Eq. (5) becomes constant if we assume that the pressure perturbation is an atmospheric front corresponding to a pressure jump over a small distance [math]l[/math]. For example, a pressure perturbation represented by [math]p = p_0 - p_1 \tanh(x/l)[/math] produces a local surface elevation jump given by [math]\Delta \zeta (x,t) \approx \Large\frac{p_1}{2\rho g l}\frac{ct}{\cosh^2((x-ct)/l)}\normalsize.[/math]

Typical values are [math]p_1 = 100 \, Pa, \; l = 5 \, 10^4 \, m, \; V \approx c = 20 \, ms^{-1} .[/math]

A more realistic model should include bathymetric slopes, wind forcing and dissipation. It can be shown that the results remain qualitatively valid if [math]ct/l[/math] is not too large[15].

Related articles

References

- ↑ Vilibic, I. and Sepic, J., 2009. Destructive meteotsunamis along the eastern Adriatic coast: overview. Phys. Chem. Earth 34: 904–917

- ↑ Pattiaratchi, C. and Wijeratne, E.M.S. 2014. Observations of meteorological tsunamis along the south-west Australian coast. Nat. Hazards 74: 281–303

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Proudman, J. 1929. The effects on the sea of changes in atmospheric pressure. Geophys J. Int. 2: 197–209 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "P" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Churchill, D.D., Houston, S.H. and Bond, N.A. 1995. The daytona beach wave of 3–4 July 1992: a shallow-water gravity wave forced by a propagating squall line. Bull Am Meteor Soc 76:21–32

- ↑ Williams, D.A., Horsburgh, K.J., Schultz, D.M. and Hughes, C.W. 2019. Examination of generation mechanisms for an English channel meteotsunami: combining observations and modeling. J Phys Oceanogr 49:103–120

- ↑ Williams, D.A., Schultz, D.M., Horsburgh, K.J. and Hughes, C.W. 2021. An 8-yr meteotsunami climatology across Northwest Europe: 2010–17. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 51: 1145–1161

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Zemunik, P., Denamiel, C., Sepic, J. and Vilibic, I. 2022. High-frequency sea-level analysis: Global distributions. Global and Planetary Change 210, 103775

- ↑ Linares, A., Wu, C.H., Bechle, A.J., Anderson, E.J. and Kristovich, D.A.R. 2019. Unexpected rip currents induced by a meteotsunami. Nature Sci. Rep. 9: 2105

- ↑ Villalonga, J., Monserrat, S., Gomis, D. and Jordà, G. 2024. Observational characterization of atmospheric disturbances generating meteotsunamis in the Balearic Islands. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 129, e2024JC020910

- ↑ De Jong, M.P.C. 2004. Origin and prediction of seiches in Rotterdam harbour basins. PhD thesis Delft University.

- ↑ Wijeratne, E. M. S. and Pattiaratchi, C. B. 2024. Meteotsunamis generated by thunderstorms. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 129, e2023JC020662

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Monserrat, S., Vilibic, I. and Rabinovich, A.B. 2006. Meteotsunamis: atmospherically induced destructive ocean waves in the tsunami frequency band. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 6: 1035–1051

- ↑ Rabinovich, A.B. 2009. Seiches and harbor oscillations. In: Handbook of Coastal and Ocean Engineering (Ed. Y.C. Kim). World Scientific Publ., Singapore

- ↑ Heidarzadeh, M. and Rabinovich, A.B. 2021. Combined hazard of typhoon-generated meteorological tsunamis and storm surges along the coast of Japan. Nat. Hazards 106: 1639–1672

- ↑ Williams, D.A., Horsburgh, K.J., Schultz, D.M. and Hughes, C.W., 2021. Proudman resonance with tides, bathymetry and variable atmospheric forcings. Nat. Hazards 106: 1169–1194

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|