Nutrient conversion in the marine environment

Although there is uncertainty about the estimates of nutrient conversion in the marine environment, it is widely believed that the underlying biogeochemical processes largely take place in the sediment of the continental shelf. This article provides a brief introduction to the processes involved in the conversion of the main nutrients: nitrogen, phosphorus and silicon.

Contents

Nutrient sources

Nutrients in coastal environments come from various sources - from rivers, atmospheric deposition, groundwater and from in situ biological fixation, see also What causes eutrophication? Rivers are the main transport route of nutrients to the coastal oceans. Riverine inputs of N (nitrogen, in the form of nitrate NO3- and ammonia NH3) and P (phosphorus, in the form of orthophosphate PO43-) have doubled in the period 1960-1990[1]. This is especially due the strongly increased use of synthetically produced fertilizers in agriculture. Other anthropogenic inputs include point-source discharges of wastewater from urban sewer networks[2] and industrial wastes. Natural processes, such as weathering of rock [3] and terrestrial nitrogen fixation[4] also contribute to the fluvial N discharge. Around 2015, global N discharge via rivers to coastal waters was estimated at 35–50 Tg N/year [5][6][7][8][9]. The estimated discharge of reactive (available for uptake) phosphorus P was in the range 2-5 Tg P/yr [10][1][5][9] (1 Tg = 1012 g = 1 billion kg). Groundwater discharge of nutrients to coastal waters could be about three times greater than global nutrient discharge via rivers, but estimates have large uncertainties[11]. Atmospheric deposition contributes about 8 Tg N/yr to the continental shelves and about 40-50 Tg/yr to the global ocean[6]. However, atmospheric deposition differs between regions. For instance, atmospheric deposition amounts to 30% of the total land-based nitrogen input to the North Sea, mainly as oxidized N, and 50% to the Baltic Sea[12] . The N:P ratio for wet deposition in the North Sea (1990) is 503:1[13], very different from the Redfield ratio 16:1 (average N:P ratio of phytoplankton).

In addition to imports from land, certain diazotrophic (nitrogen-fixing) cyanobacteria (e.g. the photoautotroph Trichodesmium and the unicellular symbiont UCYN-A[14][15]) convert dissolved N2 into ammonia (NH4+) in the sea - predominantly in the warm, well-lit low latitude ocean. This N2 fixation process (diazotrophy) is catalyzed by the enzyme nitrogenase. The amount of nutrient N that through this process becomes available in the global ocean is estimated in the order of 70-170 N Tg/yr[16][17][18]. In low-oxygen regions of the deep sea, N2 is also fixated through another process, in which certain aphotic (not requiring light) bacteria and archaea play a role. Although the fixation rate is very low, due to the enormous ocean volume, this process can still make a major contribution to the oceanic stock of nutrient N. Estimates range from 13 to 134 Tg N / yr [19]. Nitrogen fixation also occurs in the coastal zone, especially in benthic ecosystems, adding about 15 Tg N / yr to the global nutrient stock[17].

While nitrogen and phosphorus are essential nutrients for all marine primary producers, silicon (Si) is an essential nutrient only for certain organisms, in particular diatoms, silicoflagellates, rhizarians, certain radiolarians and silicious sponges. Dissolved Si (dSi), mainly as undissociated monomeric silicic acid, Si(OH)4, is the only Si compound available for uptake by marine organisms. Fluvial runoff is the main dSi supplier to the marine environment; other sources are (in decreasing order) submarine groundwater, dissolution of minerals, hydrothermal activity, aeolian dust and deglaciation. However, a large pool of dSi exists in the deep ocean. Part of this dSi pool becomes available to silicifying organisms in marine upwelling zones[20]. .

Nutrient cycling

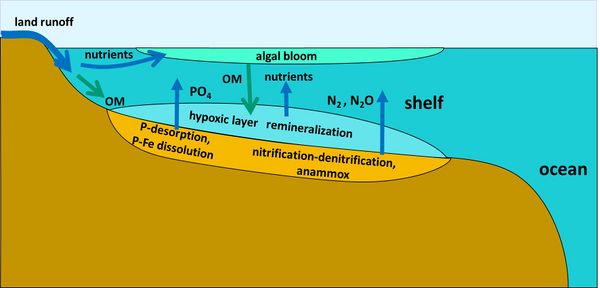

Nutrient cycling is a process in which marine microorganisms play a crucial role. The key steps of the process are the uptake of nutrients by phytoplankton for the production of organic matter and the subsequent release of these nutrients during respiration and mineralization of organic matter by bacteria, making these nutrients available again for absorption, see Plankton bloom. Coastal shelf seas are zones of intense nutrient cycling which enhances primary productivity[21]. It is estimated that shelf seas account for up to 80% of global benthic mineralization, despite covering only 7% of the seafloor [22]. Most mineralization takes place when detrital plankton settles to the bottom, either under aerobic or under anaerobic conditions. In coarse grained sediments, organic matter is rapidly mineralized, because of the high availability of oxygen that penetrates deep into the sediment[23]. The oxygen consumption is therefore high and the stock of organic carbon low[24]. Mineralization is enhanced in the presence of bioturbating benthic macrofauna[25] (Fig. 1). In fine-grained cohesive sediments, oxygen hardly penetrates the sediment bed; anoxic mineralization is relatively more important and the organic carbon content is higher[26]. There is relatively less deposition of organic material on the seabed in deeper parts of the continental shelf and the ocean because decomposition of detrital organic material (phytoplankton, zooplankton, …) first takes place in the water column[27]. See also Ocean carbon sink.

Nutrient transformation

Nitrogen

N species in aquatic environments include dissolved (nitrate NO3-, nitrite NO2-, ammonium NH4+, organic N) and particulate (organic N) constituents[28]. The removal of N occurs by deposition and permanent burial in sediments and, most importantly, by release to the atmosphere as a result denitrification coupled with organic matter decomposition. Denitrification is the conversion of nitrate into quasi-inert gases N2 (dinitrogen) and N2O (nitrous oxide) by microbial oxidation of organic matter. It is a heterotrophic process that takes place at low oxygen concentrations (of the order of 0.2 mg O2 /l or less[29][21]). Bacteria capable of denitrification are omnipresent; the determining factors for denitrification are therefore the conditions of nitrate or nitrite availability, the absence of oxygen as well as the presence of highly labile organic carbon (for example, extracellular polymeric substances EPS secreted by marine microorganisms). This labile carbon serves as electron donor in the anaerobic denitrification process. Before denitrification can take place, ammonia must first be converted into nitrite and then nitrate. The nitrite step can be skipped if comammox bacteria are present that convert ammonia directly into nitrate (COMplete AMMonia OXidation). Nitrification is a process of biological oxidation performed by autotrophic bacteria and archaea that require oxygen. Therefore, simultaneous nitrification and denitrification can only take place in special environments. Muddy shelf-sea sediments are a special environment that lends itself very well to the nitrification and denitrification steps[30][29]. Nitrate formed by nitrification in the aerobic surface sediment layer diffuses into the suboxic layer below where denitrification occurs. Denitrification can also take place in the absence of organic matter by anaerobic ammonium oxidation. This microbial process, called anammox, converts nitrite and ammonium ions directly into diatomic nitrogen N2 and water[31]. Biological activity of macrofauna can considerably extent the depth range of the oxic/suboxic interface and therefore increase the amount of denitrification[32].

Bacteria that accomplish denitrification compete with other microbes that reduce nitrate into ammonium. In this process, called DNRA (Dissimilatory Reduction of Nitrate to Ammonium), nitrogen is not removed from the ecosystem, but remains available for uptake by phytoplankton. Marine microorganisms capable of performing DNRA are commonly found in low oxygen environments, such as oxygen minimum zones in the water column, or hypoxic sediments. Ammonium produced by DNRA can be converted to dinitrogen gas by anammox bacteria.

Globally, most denitrification is believed to take place in shelf-sea sediments (Fig. 2). The amount of N denitrified in shelf-sea sediments is estimated to be in the range 200-300 N Tg / yr[29]. Denitrification also takes place in other ocean regions, especially the hypoxic zones in the Eastern Tropical North Pacific, the Eastern Tropical South Pacific and the Arabian Sea (see Possible consequences of eutrophication). Here it is estimated that about 50-100 N Tg / yr nitrate is denitrified, which is supplied to these regions via upwelling ocean currents[33][29].

Denitrification also occurs in estuaries. Significant denitrification has been observed where a strong estuarine turbidity maximum is present[34]; it is surmised that aerobic degradation of suspended organic particles creates hypoxic microniches for the growth of denitrifying bacteria. Important denitrification has also been reported in benthic intertidal ecosystems, both in the freshwater and salt water tidal reaches[35], with possibly an important role for microalgae[36]. A field study in a tropical estuary (Northern Australia) revealed intertidal mudflats per unit area to be hotspots of N removal, with higher denitrification efficiency than other benthic habitats, including mangrove and saltmarsh[37].

Denitrification is enhanced with increasing temperatures, at least partly because higher temperatures favour anoxic conditions[38]. There is also evidence that denitrifying microbial communities are sensitive to salinity fluctuations[39].

Phosphorus

Phosphorus (P) compounds discharged by rivers into the coastal ozone include dissolved constituents (inorganic DIP, organic DOP) and particulate constituents (inorganic PIP, organic POP). Most of the non-reactive PIP (not available for biologic uptake, e.g. apatite) is deposited on the continental shelf and does not reach the ocean[41]. Much of the phosphate discharge is adsorbed onto clay particles with iron-manganese oxide / oxyhydroxides on their surface. Clay particles are commonly trapped in estuaries, but the phosphate is released into the sea under conditions of increased salinity[42][43]. It has been estimated that the total load of P which desorbs from clay particles is 2-5 times more than the dissolved phosphate load which enters the ocean via rivers[41]. Hypoxia (low oxygen) conditions in coastal waters promote the release of dissolved phosphorus from sediments in which P is associated with Fe[44]. This hypoxia-related regeneration of DIP can sustain or enhance algal blooms (Fig 2).

Part of the non-reactive P is released into sediment pore waters during diagenesis and the subsequent flux into bottom waters may also contribute to the oceanic P cycle[41]. The dissolved inorganic phosphorus (usually as orthophosphate PO43-) is transformed into DOP when assimilated by phytoplankton and returns to the P pool after mineralization of planktonic detritus or detritus of higher trophic organisms. In the oceans, most of the DOP is mineralized in the surface layer. The DOP that sinks to deep ocean layers persists several thousand years. The amount of (mostly reactive) P buried in the ocean marine sediments is estimated in the order of 3-10 Tg / yr[45].

Further removal of P can occur through bacterial reduction of phosphate to gaseous phosphine. However, little is known about the rate of phosphate-phosphine transformation and its contribution to overall P cycling[46] [28].

Silicon

Silicon (Si) is present in the marine environment in different forms, mainly as dissolved Si ( dSi) and as particulate Si (biogenic silica, bSiO2, also known as opal), which includes the amorphous silica in both living biomass and biogenic detritus in surface waters, soils and sediments. The main transformation processes are the uptake of dSi and the biomineralisation as bSiO2 in plants and organisms, as well as the dissolution of bSiO2 back to dSi. Over sufficiently long time scales, bSiO2 can undergo significant chemical and mineralogical transformations[47], even including a complete diagenetic transformation of the opaline silica into alumino-silicate minerals[48]. Diatoms are the major producers of bSiO2 in marine environment, while radiolarians, sponges and chrysophytes can be important local sources of bSiO2[49]. The annual global marine production of biogenic silica bSiO2 is estimated to be 7000-8000 Tg Si/yr[2]. Most bSi that is synthesized in the surface ocean is solubilized back to silicic acid in situ, with around one third of new production surviving dissolution in the ocean interior to reach the seafloor[50]. Most of the deposited bSi is recycled at the sediment-water interface and only a tiny fraction of about 250 Tg/yr is eventually buried and removed from the Si pool. Treguer et al. (2021)[2] estimated the total oceanic dSi pool to be in the order of 3,360,000 Tg dSi, for the largest part contained in the deep ocean.

The external supply of dissolved Si is mainly carried to the sea as weathering product with river water. The total dSi input, to which some other sources also contribute, is estimated at 340-490 Tg Si/yr[2]. A comparable amount is lost from the marine dSi pool, mainly through burial in the seabed, and further through so-called reverse weathering (e.g. transformation of bSi to a neoformed aluminosilicate phase or authigenic clay formation) and by reef-building silicious sponges[2]. Although these fluxes are much smaller than the marine dSi pool, local dSi concentrations are sensitive to modifications in the supply and sink fluxes. Climate change and sediment retention in upstream reservoirs behind river dams can have a considerable impact on the dSi availability in ocean regions. A significant alteration of the Si cycle has already been observed in coastal zones downstream of some rivers with large reservoirs (e.g. Nile, Danube) while more river dams are expected to be built in the future [20]. Due to Si limitation, diatoms will become less abundant in these coastal zones relative to non-siliceous phytoplankton[51]. Global warming will increase stratification of the surface ocean, leading to a decrease in dSi inputs from the deep sea. In the polar regions, however, more dSi will become available as a result of ice melting. Model simulations suggest that diatom biomass will decline globally over the next century, except in the Southern Ocean[52][53].

Trace metals

Very small amounts of dissolved metals (so-called 'trace metals', iron Fe, manganese Mn, zinc Zi, copper Cu, cobalt Co, nickel Ni, cadmium Cd) play a crucial role in biogeochemical cycles. Trace metals are transported to the continental shelves via rivers and estuaries (where part of the metals are trapped by adsorption to fine sedimentary particles). Fe and Mn are transported to the oceans mainly as dust via the atmosphere. Trace metals are converted to biologically available forms by photochemical processes and biochemical processes mediated by microorganisms.[54] Rapid cycles of uptake and release occur in the ocean's surface layer, where concentrations are extremely low. Trace metals are involved in the regulation of metabolic processes by metalloenzymes. They are also structural elements in some proteins. At high concentrations, trace metals are toxic, but deficiency leads to disruption of essential biological processes. These processes are tuned to naturally occurring trace metal concentrations over evolutionary timescales and do not tolerate large deviations from the natural range of variation. Ocean acidification may affect the bioavailability of trace metals; however, the underlying processes are complex and not yet fully understood – see Ocean acidification#Bioavailability of trace metals.

Phytoplankton blooms can be indirectly limited by Fe depletion, since Fe is a crucial trace metal for nitrogen fixation by Trichodesmium bacteria. Low metal availability can disrupt the nitrogen cycle since nitrogen transformation processes involve metalloenzymes (Fe, Cu, Mo). Trace metals are also crucial in other processes, such as carbon fixation (requiring Fe, Mn), remineralization of organic matter (requiring Fe, Zn), methane oxidation (requiring Cu), calcification (requiring Zn, Co) and silica uptake (requiring Zn, Cd, Se).[54]

Related articles

- What causes eutrophication?

- Possible consequences of eutrophication

- Marine microorganisms

- Plankton bloom

- Open ocean habitat

- Deep sea habitat

- Other articles in the Category:Eutrophication.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Beusen, A. H. W., Bouwman, A. F., Van Beek, L. P. H., Mogollón, J. M. and Middelburg, J.J. 2015. Global riverine N and P transport to ocean increased during the twentieth century despite increased retention along the aquatic continuum. Biogeosciences Discuss. 12: 20123–20148

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Tuholske, C., Halpern, B.S., Blasco, G., Villasenor, J.C., Frazier, M. and Caylor, K. 2021. Mapping global inputs and impacts from of human sewage in coastal ecosystems. PLoS ONE 16(11), e0258898 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "T21" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Houlton, B.Z., Morford, S.L. and Dahlgren, R.A. 2018. Convergent evidence for widespread rock nitrogen sources in Earth’s surface environment. Science 360: 58–62

- ↑ Davies‐Barnard, T. and Friedlingstein, P. 2020. The global distribution of biological nitrogen fixation in terrestrial natural ecosystems. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 34, e2019GB006387

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Beusen, A.H.W. and Bouwman, A.F. 2022. Future projections of river nutrient export to the global coastal ocean show persisting nitrogen and phosphorus distortion. Front. Water 4, 893585

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Malone, T.C. and Newton, A. 2020. The Globalization of Cultural Eutrophication in the Coastal Ocean: Causes and Consequences. Front. Mar. Sci. 7: 670

- ↑ Yamamoto, A., Hajima, T., Yamazaki, D., Aita, M.N., Ito, A., Kawamiya, M. 2022. Competing and accelerating effects of anthropogenic nutrient inputs on climate-driven changes in ocean carbon and oxygen cycles. Science Advances 8, eabl9207

- ↑ Tivig, M., Keller, D.P. and Oschlies, A. 2021. Riverine nitrogen supply to the global ocean and its limited impact on global marine primary production: a feedback study using an Earth system model. Biogeosciences 18: 5327–5350

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Micella, I., Kroeze, C., Bak, M.P. and Strokal, M. 2024. Causes of coastal waters pollution with nutrients, chemicals and plastics worldwide. Marine Pollution Bulletin 198, 115902

- ↑ Seitzinger, S.P., Mayorga, E., Bouwman, A.F., Kroeze, C., Beusen, A.H.W., Billen, G., Van Drecht, G., Dumont, E., Fekete, B.M., Garnier, J. and Harrison, J.A. 2010. Global river nutrient export: A scenario analysis of past and future trends. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 24, Gb0a08

- ↑ Wilson, S.J., Moody, A., McKenzie, T., Cardenas, M.B., Luijendijk, e., Sawyer, A.H., Wilson, A., Michael, H.A., Xu, B., Knee, K.L., Cho, H-M., Weinstein, Y., Paytan, A., Moosdorf, N., Chen, C-T., A., Beck, M., Lopez, C., Murgulet, D., Kim, G., Charette, M.A., Waska, H., Ibanhez, S.P., Chaillou, G., Oehler, T., Onodera, S-I., Saito, M., Rodellas, V., Dimova, N., Montiel, D., Dulai, H., Richardson, C., Du, J., Petermann, E., Chen, X., Davis, K.L., Lamontagne, S., Sugimoto, R., Wang, G., Li, H., Torres, A.I., Demir, C., Bristol, E., Connolly, C.T., McClelland, J.W., Silva, B.J., Tait, D., Kumar, B.S.K., Viswanadham, R., Sarma, V.V.S.S., Silva-Filho, E., Shiller, A., Lecher, A., Tamborski, J., Bokuniewicz, H., Rocha, C., Reckhardt, A., Böttcher, M.E., Jiang, S., Stieglitz, T., Gbewezoun, H.G.V., Charbonnier, C., Anschutz, P., Hernandez-Terrones, L.M., Babu, S., Szymczycha, B., Sadat-Noori, M., Niencheski, F., Null, K., Tobias, G., Song, B., Anderson, I.C. and Santos, I.R. 2024. Global subterranean estuaries modify groundwater nutrient loading to the ocean. Limnology and Oceanography Letters 9, 411–422

- ↑ North Sea Task Force 1993. North Sea Quality Status Report, Oslo and Paris Commissions, London. Olsen & Olsen, Fredensborg, Denmark.

- ↑ Rendell, A. R., Ottley, C. J., Jickells, T. D. and Harrison, R. M. 1993. The atmospheric input of nitrogen species to the North Sea. Tellus 45B: 53−63

- ↑ Hallstrøm, S., Benavides, M., Salamon, E.R., Arístegui, J. and Riemann, L. 2022. Activity and distribution of diazotrophic communities across the Cape Verde Frontal Zone in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean. Biogeochemistry 160: 49-67

- ↑ Martínez-Pérez, C., Mohr, W., Löscher, C., Dekaezemacker, J., Littmann, S., Yilmaz, P., Lehnen, N., Fuchs, B.M., Lavik, G., Schmitz, R.A., LaRoche, J. and Kuypers, M.M.M. 2016. The small unicellular diazotrophic symbiont, UCYN-A, is a key player in the marine nitrogen cycle. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16163

- ↑ Galloway, J. N., Dentener, F. J., Capone, D. G., Boyer, E. W., Howarth, R. W., Seitzinger, S. P., Asner, G.P., Cleveland, C.C., Green, P.A., Holland, E.A., Karl, D.M., Michaels, A.F., Porte, J.H., Townsend, A.R. and Vorosmarty, C.J. 2004. Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future. Biogeochemistry 70: 153–226

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Voss, M., Bange, H.W., Dippner, J.W., Middelburg, J.J., Montoya, J.P. and Ward, B. 2013 The marine nitrogen cycle: recent discoveries, uncertainties and the potential relevance of climate change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc .B 368: 20130121

- ↑ Tang, W., Li, Z. and Cassar, N. 2019. Machine learning estimates of global marine nitrogen fixation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 124: 717–730

- ↑ Benavides, M., Bonnet, S., Berman-Frank, I. and Riemann, L. 2018. Deep Into Oceanic N2 Fixation. Front. Mar. Sci. 5: 108

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ittekkot, V., Humborg, C. and Schaefer, P. 2000. Hydrological alternations and marine biogeochemistry: a silicate issue? BioScience 50: 776–82

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 De Borger, E., Braeckman, U. and Soetaert, K. 2021. Rapid organic matter cycling in North Sea sediments. Continental Shelf Research 214: 104327

- ↑ Wollast, R. 1998. Evaluation and comparison of the global carbon cycle in the coastal zone and in the open ocean . In: Brink, K.H., Robinson, A. (Eds.), The Sea. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, pp. 213–252

- ↑ Huettel, M., Berg, P. and Kostka, J.E. 2014. Benthic exchange and biogeochemical cycling in permeable sediments. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 6: 23–51

- ↑ Braeckman, U., Foshtomi, M.Y., Van Gansbeke, D., Meysman, F., Soetaert, K., Vincx, M. and Vanaverbeke, J. 2014. Variable importance of macrofaunal functional biodiversity for biogeochemical cycling in temperate coastal sediments. Ecosystems 17: 720–737

- ↑ Toussaint, E., De Borger, E., Braeckman, U., De Backer, A., Soetaert, K. and Vanaverbeke, J. 2021. Faunal and environmental drivers of carbon and nitrogen cycling along a permeability gradient in shallow North Sea sediments. Science of the Total Environment 767: 144994

- ↑ Canfield, D., Jørgensen, B., Fossing, H., Glud, R., Gundersen , J., Ramsing, N., Thamdrup, B., Hansen, J., Nielsen, L. and Hall, P.O. 1993. Pathways of organic carbon oxidation in three continental margin sediments. Mar. Geol. 113: 27–40

- ↑ Middelburg, J.J., Soetaert, K., Herman, P.M.J. and Heip, C.H.R. 1996 Denitrification in marine sediments: a model study. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 10: 661–673

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Tappin, A.D. 2000. An Examination of the Fluxes of Nitrogen and Phosphorus in Temperate and Tropical Estuaries: Current Estimates and Uncertainties, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 55: 885-901

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Seitzinger, S., Harrison, J.A., Bohlke, J.K., Bouwman, A.F., Lowrance, R., Peterson, B., Tobias, C. and Van Drecht, G. 2006. Denitrification across landscapes and waterscapes: A synthesis. Ecological Applications 16: 2064–2090

- ↑ Malcolm, S.J. and Sivyer, D.B. 1997. Nutrient recycling in intertidal sediments. in Jickells, T. and Rae, J.E. (Eds) Biogeochemistry of Intertidal Sediments. Cambridge University Press, pp. 59–83

- ↑ Burgin, A. and Hamilton, S. 2007. Have we overemphasized the role of denitrification in aquatic ecosystems? A review of nitrate removal pathways. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 5: 89-96

- ↑ Rysgaard, S. B., Christensen, P.B. and Nielsen, L. P. 1995. Seasonal variation in nitrification and denitrification in estuarine sediment colonized by benthic microalgae and bioturbating fauna. Marine Ecology Progress Series 126: 111–121

- ↑ Deutsch, C., Gruber, N., Key, R. M. and Sarmiento, J. L. 2001. Denitrification and N2 fixation in the Pacific Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 15: 483–506

- ↑ Zheng, Y., Hou, L., Zhang, Z., Ge, J., Li, M., Yin, G., Han, P., Dong, H., Liang, X., Gao, J., Gao, D. and Liu, M. 2021. Overlooked contribution of water column to nitrogen removal in estuarine turbidity maximum zone (TMZ). Science of the Total Environment 788: 147736

- ↑ O'Connor, J.A., Erler, D.V., Ferguson, A. and Mahler, D.Y. 2022. The tidal freshwater river zone: Physical properties and biogeochemical contribution to estuarine hypoxia and acidification - The “hydrologic switch”. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 268, 107786

- ↑ Laverman, A.M., Morelle, J., Roose-Amsaleg, C. and Pannard, A. 2021. Estuarine benthic nitrate reduction rates: Potential role of microalgae? Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 257, 107394

- ↑ Fortune, J., Butler, E.C.V. and Gibb, K. 2023. Estuarine benthic habitats provide an important ecosystem service regulating the nitrogen cycle. Marine Environmental Research 190, 106121

- ↑ Veraart, A.J., de Klein, J.J. and Scheffer, M. 2011. Warming can boost denitrification disproportionately due to altered oxygen dynamics. PLoS One 6(3):e18508

- ↑ Marks, B.M., Chambers, L. and White, J.R. 2016. Effect of Fluctuating Salinity on Potential Denitrification in Coastal Wetland Soil and Sediments. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 80: 516–526

- ↑ Dai, M., Zhao, Y., Cha,i F., Chen, M., Chen, N., Chen, Y., Cheng, D., Gan, J., Guan, D., Hong, Y., Huang, J., Lee, Y., Leung, K.M.Y., Lim, P.E., Lin, S., Lin, X., Liu, X., Liu, Z., Luo, Y-W., Meng, F., Sangmanee, C., Shen, Y., Uthaipan, K., Wan Talaat, W.I.A., Wan, X.S., Wang, C., Wang, D., Wang, G., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Xu, Y., Yang, J-Y.T,, Yang, Y., Yasuhara, M., Yu, D., Yu, J., Yu, L., Zhang, Z. and Zhang, Z. 2023. Persistent eutrophication and hypoxia in the coastal ocean. Cambridge Prisms: Coastal Futures 1, e19, 1–28

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Paytan, A. and McLaughlin, K. 2007. The Oceanic Phosphorus Cycle. Chem. Rev. 107: 563-576

- ↑ Krom, M.D. and Berner, R.A. 1980. Adsorption of phosphate in anoxic marine sediments, Limnology and Oceanography 25: 797-806

- ↑ Frossard, E., Brossard, M., Hedley, M.J. and Metherell, A. 1995. Reactions controlling the cycling of P in soils. Phosphorus in the global environment, H. Tiessen, Ed. (John Wiley & Sons Ltd.), pp. 107-138

- ↑ Middelburg, J.J. and Levin, L.A. 2009. Coastal hypoxia and sediment biogeochemistry. Biogeosciences 6: 1273–1293

- ↑ Benitez-Nelson, C.R. 2000. The biogeochemical cycling of phosphorus in marine systems. Earth-Science Reviews 51: 109-135

- ↑ Gassman, G. 1994. Phosphine in the fluvial and marine hydrosphere. Marine Chemistry 45: 197–205

- ↑ Van Cappellen, P., Dixit, S. and van Beusekom, J. 2002. Biogenic silica dissolution in the oceans: Reconciling experimental and field-based dissolution rates, Global Biogeochemical Cycles 16, 1075, doi:10.1029/2001GB001431

- ↑ Michalopoulos, P., Aller, R.C. and Reeder, R.J. 2000. Conversion of diatoms to clays during early diagenesis in tropical, continental shelf muds, Geology 28: 1095-1098

- ↑ Simpson, T.L. and Volcani, B.E. 1981. Silicon and Siliceous Structures in Biological Systems, Springer-Verlag NY, 587 pp

- ↑ Tréguer, P. J. and De La Rocha, C. L. 2013. The World Ocean silica cycle. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 5: 477–501

- ↑ Humborg, C., Conley, D.J., Rahm, L., Wulff, F., Cociasu, A. and Ittekkot, V. 2000. Silicon retention in river basins: far-reaching effects on biogeochemistry and aquatic food webs in coastal marine environments. Ambio 29: 45–50

- ↑ Bopp, L., Aumont, O., Cadule, P., Alvain, S. and Gehlen, M. 2005. Response of diatoms distribution to global warming and potential implications: A global model study. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32: 2– 5

- ↑ Laufkötter, C., Vogt, M., Gruber, N., Aita-Noguchi, M., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., Buitenhuis, E., Doney, S. C., Dunne, J., Hashioka, T., Hauck, J., Hirata, T., John, J., Le Quéré, C., Lima, I. D., Nakano, H., Seferian, R., Totterdell, I., Vichi, M. and Völker, C. 2015. Drivers and uncertainties of future global marine primary production in marine ecosystem models. Biogeosciences 12: 6955– 6984

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Morel, F.M.M. and Price, N.M. 2003. The biogeochemical cycles of trace metals in the oceans. Science 300: 944–947

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|