Ocean acidification

Definition of Ocean acidification:

The process whereby atmospheric carbon dioxide dissolved in seawater produces carbonic acid, which lowers the ocean pH – a process thought to be happening on a global scale.

This is the common definition for Ocean acidification, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

This article introduces processes involved in ocean acidification and summarizes results from studies on the impact of ocean acidification on a few common calcifying marine organisms. Ocean acidification is mainly a result of the anthropogenic release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The article begins by defining ocean acidity and the related concept of alkalinity. It further explains the counterintuitive result that calcifying organisms promote acidification, while dissolution of calcium carbonate counteracts acidification and promotes the uptake of atmospheric [math]CO_2[/math].

Contents

- 1 Ocean acidity

- 2 Alkalinity

- 3 Carbonate chemistry

- 4 Feedbacks to acidification

- 5 Deep sea carbonate dissolution

- 6 Ecosystem impacts of ocean acidification

- 7 Influence of ocean acidification on a few bivalve species

- 8 Influence of ocean acidification on coccolithophores

- 9 Bioavailability of trace metals

- 10 Related articles

- 11 References

Ocean acidity

The unit for measuring ocean acidity is the [math]pH[/math]. [math]pH[/math] is a measure of hydrogen ion [math]H^+[/math] activity[1]. Because ion activity cannot be measured directly, [math]pH[/math] is often estimated from the approximate formula

[math]pH \approx - log_{10} ([H^+]) , \qquad (1)[/math]

where [math][H^+]= c_{eq}(H^+)[/math] is the equilibrium concentration (measured in number of moles per liter) of [math]H^+[/math] ions at temperature [math]25 ^oC[/math] and practical salinity 35. A solution is neutral if [math]pH=7[/math], acidic if [math]pH\lt 7[/math] and basic if [math]pH\gt 7[/math].

The average acidity of ocean surface waters was [math]pH=8.15[/math] in pre-industrial times. Due to the increase in the atmospheric [math]CO_2[/math] concentration, the amount of [math]CO_2[/math] dissolved in the ocean has also increased. It is estimated that about 30% of the yearly emitted [math]CO_2[/math] is absorbed by the oceans[2]. The uptake of [math]CO_2[/math] has raised the acidity (decreased the [math]pH[/math]) of the ocean surface waters in 2020 to about [math]pH=8.05[/math]. This is equivalent to an increase of hydrogen ion activity of about 26%.

The average acidity of ocean surface waters is expected to decrease by 0.14–0.43 units (i.e., a decrease in [math]pH[/math] from about 8.15 to about 7.7 - 8) with a concurrent increase of 2-4 oC in sea surface temperature by 2100.[3]

Ocean acidification is not only due to uptake of atmospheric [math]CO_2[/math]. Other processes also contribute to acidification, such as calcification, decomposition of organic material, nitrification in surface water (promoted by sewage discharge) and oxidation processes in sediments[4]. Acidity is not directly related to the presence of dissolved oxygen, because [math]O_2[/math] and [math]H^+[/math] do not react to produce [math]H_2O[/math].

Alkalinity

Alkalinity plays a major role in ocean chemistry, in [math]CO_2[/math] storage and in calcium carbonate precipitation and dissolution. Alkalinity is defined as the excess of proton acceptors (typically anions) over donors (typically free protons [math]H^+[/math]) in seawater[5]. Alkalinity and [math]pH[/math] are in general positively correlated.

Total alkalinity (TA) is a measure of the capacity of seawater to resist sudden changes in [math]pH[/math] by absorbing hydrogen ions, using available bases such as [math]HCO_3^-[/math] and [math]CO_3^{2-}[/math]. It is an indicator of the ocean's capacity to store [math]CO_2[/math]. Total alkalinity is given by the equation[6]:

[math]TA = [HCO_3^-] + 2 \, [CO_3^{2-}] + [OH^-] - [H^+] + \mathrm{minor \, compounds} ,[/math]

where [math][ .. ][/math] indicates the equilibrium concentration. Alkalinity can be determined by measuring the quantity of a strong acid that must be supplied to convert all anions in uncharged species[7].

Natural weathering of rocks is the primary source of oceanic alkalinity. For example, the dissolution of olivine (a ubiquitous mineral in mafic rocks) according to [math]\; Mg_2SiO_4 + 2CO_2 + 2H_2O \rightarrow 2MgCO_3 + H_4SiO_4 \;[/math], consumes 2 moles of aqueous CO2 to produce 2 carbonate ions. These carbonate ions combine primarily with hydrogen protons to form bicarbonate ions.[8]

Oxidation reactions involving oxygen (e.g. aerobic mineralization) generally consume alkalinity. In contrast, anaerobic processes usually produce alkalinity. For example, during denitrification (reduction of nitrate to dinitrogen gas), the charge of nitrate is transferred to bicarbonate and thus increases alkalinity. Similarly, the reduced sulfur buried in marine sediments initially entered the ocean as a sulfate ion; this implies a charge transfer to bicarbonate. Alkalinity is also generally generated by the dissolution of minerals[5].

Carbonate chemistry

The uptake of atmospheric [math]CO_2[/math] into the ocean increases the concentration of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) according to the chemical balances[9]

[math]CO_2+H_2O \rightleftharpoons H_2CO_3 \rightleftharpoons HCO_3^- + H^+ \rightleftharpoons CO_3^{2-} +2H^+ . \qquad (2)[/math]

These chemical balances depend on the ocean's acidity. At neutral conditions ([math]pH \approx 7.5[/math]), DIC in the ocean mainly consists of bicarbonate [math]HCO_3^-[/math] (90.9%) and to a lesser degree of carbonate [math]CO_3^{2-}[/math] (8.5%). Aqueous [math]\; CO_2[/math], the only form of inorganic carbon that is exchanged with the atmosphere, is only a minor component (0.6%).

As noted earlier, dissolution of [math]CO_2[/math] is not the primary source of [math]HCO_3^-[/math] to the ocean, but mineral weathering of silicate and carbonate rocks are the main sources[6].

Uptake of [math]CO_2[/math] leads to ocean acidification (increase in [math][H^+][/math]), mainly because [math]CO_2+H_2O \rightarrow HCO_3^- + H^+ [/math]. However, most hydrogen ions [math]H^+ [/math] combine with carbonate [math]CO_3^{2-}[/math], giving[10]

[math]CO_2+H_2O+ CO_3^{2-} \rightleftharpoons 2HCO_3^- . \qquad (3)[/math]

This reaction shows that uptake of [math]CO_2[/math] implies:

- fewer carbonate ions [math]CO_3^{2-}[/math] remain available for marine calcifying organisms to produce calcium carbonate [math]CaCO_3[/math] shells.

- the presence of carbonate ions reduces the partial pressure of [math]CO_2[/math] (concentration of dissolved [math]CO_2[/math]) and therefore enhances the ocean's capacity to store [math]CO_2[/math].

With decreasing acidity (increasing [math]pH[/math]), a relatively larger part of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) consists of carbonate [math]CO_3^{2-}[/math]. The ocean's capacity to store [math]CO_2[/math] increases, leading to an increase in acidity. With increasing acidity, a relatively smaller part of DIC consists of carbonate, thus decreasing the ocean's capacity to store [math]CO_2[/math].

Feedbacks to acidification

The ubiquitous presence of calcium carbonate [math]CaCO_3[/math] in the ocean provides a feedback mechanism that mitigates ocean acidification due to [math]CO_2[/math] uptake. Dissolution of calcium carbonate in seawater can follow different pathways[11],

[math]CaCO_3 \rightleftharpoons Ca^{2+}+CO_3^{2-} ; \quad CaCO_3+H_2O \rightleftharpoons Ca^{2+}+HCO_3^{-} +OH^- ; \quad CaCO_3+H_2O+CO_2 \rightleftharpoons Ca^{2+}+2HCO_3^{-} . \qquad (4) [/math]

The carbonate ions [math]HCO_3^-[/math] and [math]CO_3^{2-}[/math] produced by dissolution can combine with hydrogen ions. Dissolution of calcium carbonate thus decreases the concentration of free hydrogen ions and therefore counteracts the increase in acidity due to [math]CO_2[/math] uptake[12]. Increased alkalinity of the ocean's surface waters due to dissolution of [math]CaCO_3[/math] decreases the partial pressure of [math]CO_2[/math] in the ocean, according to Eq. (3). The capacity of the ocean to absorb atmospheric [math]CO_2[/math] is increased, thus reducing the concentration of atmospheric [math]CO_2[/math].

Conversely, calcifying organisms that extract carbonate ions from seawater promote acidification. The last member of equation (4) shows that [math]CO_2[/math] is generated in the case of [math]CaCO_3[/math] precipitation. The production of 1 mole of [math]CaCO_3[/math] consumes 2 moles of [math]HCO_3^-[/math]. The associated release of [math]CO_2[/math] contributes to increasing atmospheric [math]CO_2[/math] because ocean uptake is reduced (but a bit less reduced than Eq. (4) suggests, as the released mole of [math]CO_2[/math] is only partially buffered in the seawater). [6]

Deep sea carbonate dissolution

Ocean surface waters are typically supersaturated with calcium carbonate [math]CaCO_3[/math] due to high concentrations of calcium ions. Despite a supersaturation factor of 4 with respect to calcite and a factor 2.5 with respect to aragonite, no inorganic precipitation takes place. Precipitation in sea water is inhibited by other elements (e.g. [math]Mg^{2+}[/math])[13], but many biota have developed chemical approaches to overcome this limitation and precipitate [math]CaCO_3[/math] as calcite or aragonite.

The solubility of calcium carbonate increases when the saturation state decreases, which occurs when the concentration of carbonate ions decreases. It also decreases with increasing depth because the greater solubility of [math]CO_2[/math] at low temperature and high pressure raises the [math]pH[/math]. This explains why calcifying organisms do not occur at great depths in the ocean. The dissolution of [math]CaCO_3[/math] in the deep ocean raises the alkalinity and [math]pH[/math]. This buffer mechanism of calcium carbonate protects seawater [math]pH[/math] against significant change from uptake of atmospheric [math]CO_2[/math] [11].

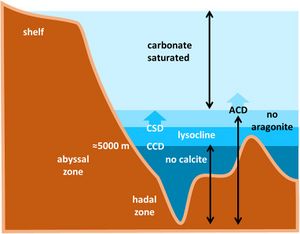

Calcium carbonate in the oceans occurs in two crystalline forms (polymorphs): aragonite and calcite. The 'lysocline' is the transition zone in the ocean within which the calcium carbonate mineral calcite becomes unstable and begins to dissolve (Fig. 1). Its upper limit is the calcite saturation depth (CSD) and its lower limit is the calcite (carbonate) compensation depth (CCD). Below the CCD seabed sediments contain little or no carbonate minerals, the so-called 'carbonate snow line'. Aragonite is much more soluble than calcite. The aragonite compensation depth (ACD) is therefore much shallower than the CCD. Organisms that produce aragonite are therefore more vulnerable to changes in ocean acidity than those that produce calcite. The dissolution of aragonite in the deep sea releases alkalinity and raises the [math]CaCO_3[/math] saturation state, thus providing a buffer against dissolution of calcite deposits[15].

Global ocean modeling suggests that the carbonate compensation depth (CCD) has already risen by nearly 100 m on average since pre-industrial times and will likely rise further by several hundred meters more this century. Potentially millions of square kilometres of ocean floor will undergo a rapid transition in terms of the overlying water chemistry whereby calcareous sediment will become unstable causing the carbonate snow line to rise. [14]

Ecosystem impacts of ocean acidification

Although there is no doubt that acidification is impacting ocean ecosystems worldwide, it is difficult to unambiguously attribute observed ecosystem changes to acidification effects. Observed changes in ocean ecosystems may also be due to natural variability, global warming, or other human impacts such as fishing or eutrophication. Long-term biological and ecological measurements to distinguish between trends and natural variability are scarce. Studies of the response of marine organisms to acidification are mainly based on controlled experiments. However, these experiments provide limited assessment of population-level impacts due to the complexity of how acidification effects may cascade through ecosystems, such as variation in the sensitivity of individuals within a community and subsequent effects on population dynamics[16].

Field-based observations of ocean acidification impacts mostly refer to natural CO2 gradients across particular ecosystems. Agostini et al. (2018[17]) compared intertidal and subtidal rocky reef communities near shallow volcanic seeps along natural gradients in CO2. These gradients corresponded to present-day to near-future levels of CO2 (300 µatm to 400 µatm), and then to future CO2 levels (400 µatm to 700 µatm), associated with decreasing levels of aragonite saturation and increasing availability of inorganic carbon. Abrupt changes in the intertidal and subtidal rocky reef communities were observed with biodiversity loss due to a decline in habitat-forming species (e.g. coralline algae, canopy-forming macroalgae, scleractinian corals, and barnacles) and an increase in low-profile and turf algae. Another study conducted near these shallow volcanic seeps showed that algal communities transplanted on recruitment tiles in these CO2-enriched waters became dominated by turf algae with lower biomass, diversity and complexity, a pattern consistent across seasons[18]. Algal communities recovered after being transplanted back to non-enriched conditions.

These observations suggest that ocean acidification will shift ecosystems at subtropical-temperate transition zones from complex calcified biogenic habitats towards less complex non-calcified habitats. Acidification may also impede the shift of corals from the (sub)tropics to higher latitudes[17]. A comprehensive open-access review of possible impacts of ocean acidification on marine benthic ecosystems is provided by Somma et al. (2023[19]).

Another impact of ocean acidification is the likely decrease in DMS production by algae, which could reduce the albedo of the oceans - see Greenhouse gas regulation.

Influence of ocean acidification on a few bivalve species

A literature review[20] indicates that most bivalves decrease metabolic activity in response to low [math]pH[/math]. However, it is also noted that bivalves from ocean regions with naturally lower [math]pH[/math] (e.g., upwelling regions) show neutral or positive responses. It also appears that bivalves in warmer areas may be more sensitive to low [math]pH[/math].

Oyster Magallana gigas and mussel Mytilus spp.

Mytilus spp. and Magallana gigas together account for almost half of global mollusc production within the aquaculture industry. As the ocean’s [math]pH[/math] decreases, the extent of the effect of ocean acidification is dependent on the shell structure and composition of the organism. Both the mussel Mytilus species (spp.) and the oyster Magallana gigas form calcite layers, but Mytilus spp. also forms aragonite on the inner shell layer. Although the two polymorphs share the same chemical formula, the different atomic arrangement of aragonite increases susceptibility to ocean acidification, compared to calcite.

Experiments were conducted to examen the interactive effects on Mytilus spp. and Magallana gigas of [math]pH[/math] (8.1 versus 7.7), temperature (12 versus 14 oC) and feeding (control versus extra feed) in a full factorial experimental design. The following observations were reported (Mele et al., 2023[21]):

"When seawater temperature rises, Mytilus spp. appear to rely on metabolically sourced carbon for shell calcite potentially from extrapallial fluid (fluid from outside the mantle) rather than from mantle tissue or from the feed under ocean acidification. The altered biomineralization pathway in Mytilus spp. into the shell calcite layer, is sufficient to maintain the growth of the shell, as well as its thickness and hardness. On the other hand, Mytilus spp. increases environmentally sourced carbon for aragonite under low [math]pH[/math] conditions. This response is sufficient to maintain and increase shell thickness in high water temperature scenarios. Low [math]pH[/math] also affects M. gigas from a feeding and nutrient perspective shown by variation in mantle nitrogen isotopes, but biomineralization pathway is maintained along with growth.

Previous research has shown that increasing food supply to mollusks during ocean acidification experiments can limit shell corrosion and increase shell growth. However, plankton blooms would be more beneficial to M. gigas, as this study shows overall better shell performance and resilience than Mytilus spp."

White furrow shell Abra alba

A study of Vlaminck et al. (2022[22]) on the physiological response of the white furrow shell Abra alba to three [math]pH[/math] treatments ([math]pH = 8.2; \, pH = 7.9; \, pH = 7.7[/math]) showed no [math]pH[/math] effect on survival.

"However, lowered respiration and calcification rates, decreased energy intake (lower absorption rate) and increased metabolic losses (increased excretion rates) occurred at [math]pH \sim 7.7 [/math]. These physiological responses resulted in a negative Scope for Growth and a decreased condition index at this [math]pH[/math]. This suggests that the physiological changes may not be sufficient to sustain survival in the long term, which would undoubtedly translate into consequences for ecosystem functioning."

Peruvian scallop Argopecten purpuratus

Along the Peruvian coast, natural conditions of low [math]pH[/math] (7.6–8.0) are encountered in the habitat of the Peruvian scallop Argopecten purpuratus, due to the nearby coastal upwelling. During 28 days, scallops (initial mean height = 14 mm) were exposed to two contrasted pH conditions: a control with unmanipulated seawater presenting [math]pH[/math] conditions similar to those found in situ ([math]pH = 7.8[/math]) and a treatment, in which CO2 was injected to lower the [math]pH[/math] to 7.4.

"At the end of the experiment, shell height and weight, and growth and calcification rates were reduced about 6%, 20%, 9%, and 10% respectively in the low [math]pH[/math] treatment. Mechanical properties, such as microhardness were positively affected in the low [math]pH[/math] condition and crushing force did not show differences between [math]pH[/math] treatments. Final soft tissue weights were not significantly affected by low [math]pH[/math]. This study provides evidence of low [math]pH[/math] change shell properties increasing the shell microhardness in Peruvian scallops, which implies protective functions" (Cordova-Rodriguez et al., 2022[23]).

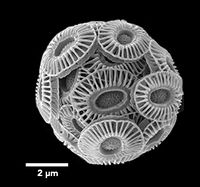

Influence of ocean acidification on coccolithophores

Coccolithophores are unicellular organisms belonging to the marine phytoplankton community. The most common species is Emiliania huxleyi, ubiquitous in temperate, subtropical and tropical oceans. Coccolithophores are covered with calcium carbonate scales called coccoliths. Coccoliths from dead coccolithophores contribute to the ocean's carbon sink. Dead coccolithophores sink slowly and a large fraction is probably mineralized before reaching the ocean floor. Coccoliths and coccospheres are more likely to be transported to depth when incorporated within fecal pellets or marine snow[24]. A major fraction of carbonate in ocean surface waters (close to 90%) consists of coccolithophores but their contribution to the [math]CaCO_3[/math] stock buried in deep sea sediments is probably not larger than the contribution of the much less abundant foraminifera[25].

Krumhardt et al. (2019[26]) studied the sensitivity of coccolithophore growth and calcification to increasing CO2 both regionally and on a global scale using the Community Earth System Model (CESM) version 2.0[27]. This model was validated by comparison with satellite-derived ocean data of particulate inorganic carbon, a compilation of coccolithophore biomass estimated from shipboard measurements, a global compilation of coccolithophore calcification rates and estimates of globally integrated annual upper ocean calcification rates.

The model results show that: "increasing CO2 stimulates the growth of coccolithophores in some regions (North Atlantic, Western Pacific, and parts of the Southern Ocean), allowing them to better compete for resources with other phytoplankton functional types in the model. As CO2 increases in the upper ocean, however, calcification is impaired. Most regions of the ocean show vast declines in pelagic calcification, with some regions (in the Southern Ocean and North Pacific) being subject to almost no calcification by coccolithophores at end-of-the-century CO2 levels. Though CO2 stimulates growth in some areas, coccolithophores in general are projected to be more lightly calcified under future, high CO2 conditions."

The findings of Ziveri et al. (2023)[25] suggest that calcium carbonate production by coccolithophores and carbon export to the deep sea are not strongly coupled. Several other processes play a role such as changes in the ability to export [math]CaCO_3[/math] out of the photic zone due to changes in grazing, particle aggregation, the organic/inorganic carbon ratio of the aggregates, or changes in the relative abundance of foraminifera to coccolithophores/pteropods. Decrease in calcification by coccolithophores generates a negative feedback to acidification. The reduced export of alkalinity enables additional dissolution of CO2, decreasing the atmospheric concentration of this greenhouse gas.

Bioavailability of trace metals

Trace metals, such as iron, nickel, copper, zinc, and cadmium, are essential for the growth and survival of microorganisms that photosynthesize the organic matter on which the ocean ecosystem depends. If trace metal concentrations become too low, photosynthesis fails; if they become too high, the excess metal can prove toxic. This is a delicate issue, as photosynthesis is evolutionarily adapted to the current concentration levels of trace metals.

For any given substance (metal, nutrient, or contaminant), the amount that can be readily metabolized is known as bioavailable. The bioavailability of metals is restricted as they form strong complexes with hydroxide and carbonate ions. Under acidified conditions (increase in free protons [math][H^+][/math]), the concentrations of the hydroxide [math][OH^-][/math] and carbonate [math][CO_3^{2-}][/math] anions will decrease. A corresponding increase in the concentration of bioavailable metals (Fe, Cu) can therefore be expected. [28] A modest increase in the availability of Fe can stimulate primary production, whereas an increase in the availability of Cu can have a toxic effect.

However, this is not the whole story, as the bioavailability of a large fraction (more than 90%) of trace metals is limited by the binding of metal ions to organic macromolecules, so-called chelation. Acidic sugars, exopolysaccharides and many other exopolymeric substances ubiquitous in seawater are excellent ligands for metal ions due to the presence of phenolic and carboxylic functional groups.[29] How these macromolecules and their bonding with metals respond to an increase in acidity is not yet fully understood. Understanding how environmental factors alter metal speciation is also critical for assessing metal bioavailability and uptake rates. For example, sunlight and reactive oxygen species can dissociate metals from organic complexes through redox mechanisms or by degrading the organic ligand. Several biochemical models have been developed to simulate the impact of ocean acidification on the bioavailability of trace metals, but these do not provide clear-cut answers due to the presence of myriad organic compounds of unknown chemistry and affinity for different metals. [30][31]

Related articles

- Ocean carbon sink

- Effects of global climate change on European marine biodiversity

- Greenhouse gas regulation

- Blue carbon sequestration

See also Wikipedia: Ocean acidification.

References

- ↑ Marion, G.M., Millero, F.J., Camoes, M.F., Spitzer, P., Feistel, R. and Chen, C.T.A. 2011. pH of seawater. Marine Chemistry 126: 89-96

- ↑ Terhaar, J., Froelicher, T.L. and Joos, F. 2022. Observation-constrained estimates of the global ocean carbon sink from Earth system models. Biogeosciences 19: 4431–4457

- ↑ Lee, J.-Y., Marotzke, J., Bala, G., Cao, L., Corti, S., Dunne, J.P., Engelbrecht, F., Fischer, E., Fyfe, J.C., Jones, C., Maycock, A., Mutemi, J., Ndiaye, O., Panickal, S. and Zhou, T. 2021. Chapter 4: Future Global Climate: Scenario-Based Projections and Near- Term Information. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, pp. 553–672

- ↑ Wallace, R.B. and Gobler, C.J. 2021. The role of algal blooms and community respiration in controlling the temporal and spatial dynamics of hypoxia and acidification in eutrophic estuaries. Marine Pollution Bulletin 172, 12908

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Middelburg, J. J., Soetaert, K. and Hagens, M. 2020. Ocean alkalinity, buffering and biogeochemical processes. Reviews of Geophysics 58, e2019RG000681

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Pernet, F., Dupont, S., Gattuso, J-P., Metian, M. and Gazeau, F. 2024. Cracking the myth: Bivalve farming is not a CO2 sink. Rev Aquac. 2024: 1–13

- ↑ Millero, F.J., Zhang, J.Z., Lee, K. and Campbell, D.M. 1993. Titration alkalinity of seawater. Mar. Chem. 44: 153–165

- ↑ Renforth, P. and Henderson, G. 2017. Assessing ocean alkalinity for carbon sequestration. Rev. Geophys. 55: 636–674

- ↑ Mehrbach, C., Culberson, C.H., Hawley, J.E. and Pytkowicz, R.M. 1973. Measurement of the apparent dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater at atmospheric pressure. Limnol. Oceanogr. 18: 897–907

- ↑ Egleston, E.S., Sabine, C.L. and François, M.M.M. 2010. Revelle revisited: Buffer factors that quantify the response of ocean chemistry to changes in DIC and alkalinity. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 24, GB1002

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Batchelor-McAuley, C., Yang, M., Rickaby, R.E.M. and Compton, R.G. 2022. Calcium Carbonate Dissolution from the Laboratory to the Ocean: Kinetics and Mechanism. Chem.Eur.J. 28, e2022022

- ↑ Zeebe, R. E. and Wolf‐Gladrow, D. 2001. CO2 in seawater: Equilibrium, kinetics, isotopes. In Elsevier Oceanography Series (360 pp.)

- ↑ Berner, R. A. 1975. The role of magnesium in the crystal growth of calcite and aragonite from sea water. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 39: 489–504

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Harris, P.T., Westerveld, L., Zhao, Q. and Costello, M.J. 2023. Rising snow line: Ocean acidification and the submergence of seafloor geomorphic features beneath a rising carbonate compensation depth. Marine Geology 463, 107121

- ↑ Sulpis, O., Agrawal, P., Wolthers, M., Munhoven, G., Walker, M. and Middelburg, J.J. 2023. Aragonite dissolution protects calcite at the seafloor. Nature Communications 13: 1104

- ↑ Doo, S.S., Kealoha, A., Andersson, A., Cohen, A.L., Hicks, T.L., Johnson, Z.I., Long, M.H., McElhany, P., Mollica, N., Shamberger, K.E.F., Silbiger, N.J., Takeshita, Y. and Busch, D.S. 2020. The challenges of detecting and attributing ocean acidification impacts on marine ecosystems. ICES Journal of Marine Science 77(7-8): 2411–2422

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Agostini, S., Harvey, B.P., Wada, S., Kon, K., Milazzo, M., Inaba, K. and Hall-Spencer, J.M. 2018. Ocean Acidification Drives Community Shifts towards Simplified Non-Calcified Habitats in a Subtropical-Temperate Transition Zone. Sci. Rep. 8, 11354

- ↑ Harvey, B.P., Kon, K., Agostini, S., Wada, S. and Hall-Spencer, J.M. 2021. Ocean Acidification Locks Algal Communities in a Species-Poor Early Successional Stage. Glob. Chang. Biol. 27: 2174–2187

- ↑ Somma, E., Terlizzi, A., Costantini, M., Madeira, M. and Zupo, V. 2023. Global Changes Alter the Successions of Early Colonizers of Benthic Surfaces. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 1232

- ↑ Czaja, R., Pales-Espinosa, E., Cerrato, R.M., Lwiza, K. and Allam, B. 2023. Using meta-analysis to explore the roles of global upwelling exposure and experimental design in bivalve responses to low pH. Science of the Total Environment 902, 165900

- ↑ Mele, I., McGill, R.A.R., Thompson, J., Fennell, J. and Fitzer, S. 2023. Ocean acidification, warming and feeding impacts on biomineralization pathways and shell material properties of Magallana gigas and Mytilus spp. Marine Environmental Research 186, 105925

- ↑ Vlaminck, E., Moens, T., Vanaverbeke, J. and Van Colen, C. 2022. Physiological response to seawater pH of the bivalve Abra alba, a benthic ecosystem engineer, is modulated by low pH. Marine Environmental Research 179, 105704

- ↑ Cordova-Rodríguez, K., Flye-Sainte-Marie, J., Fernandez, E., Graco, M., Rozas, A. and Aguirre-Velarde, A. 2022., Effect of low pH on growth and shell mechanical properties of the Peruvian scallop Argopecten purpuratus (Lamarck, 1819). Marine Environmental Research 177, 105639

- ↑ Steinmetz, J. C. 1994. Sedimentation of coccolithophores. In A. Winter, & W. G. Siesser (Eds.), Coccolithophores, (pp. 179–198). Cambridge University Press

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Ziveri, P., Gray, W.R., Anglada-Ortiz, G., Manno, C., Grelaud, M., Incarbona, A., Rae, J.W.B., Subhas, A.V., Pallacks, S., White, A., Adkins, J.F. and Berelson, W. 2023. Pelagic calcium carbonate production and shallow dissolution in the North Pacific Ocean. Nature Communications 14: 805

- ↑ Krumhardt, K. M., Lovenduski, N. S., Long, M. C., Levy, M., Lindsay, K., Moore, J. K. and Nissen, C. 2019. Coccolithophore growth and calcification in an acidified ocean: Insights from community earth system model simulations. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 11: 418-1437

- ↑ Marine Biogeochemical Library (MARBL), https://marbl-ecosys.github.io/

- ↑ Stockdale, A., Tipping, E., Lofts, S. and Mortimer, R.J.G. 2016. Effect of ocean acidification on organic and inorganic speciation of trace metals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50: 1906–1913

- ↑ Millero, F.J., Woosley, R., Ditrolio, B. and Waters, J. 2009. Effect of ocean acidification on the speciation of metals in seawater. Oceanography 22: 72–85

- ↑ Whitby, H., Park, J., Shaked, Y., Boiteau, R.M., Buck, K.N. and Bundy, R.M. 2024. New insights into the organic complexation of bioactive trace metals in the global ocean from the GEOTRACES era. Oceanography 37: 142-155

- ↑ Cheriyan, E., Kumar, B.S.K., Gupta, G.V.M. and Bhaskara Rao, D. 2024. Implications of ocean acidification on micronutrient elements-iron, copper and zinc, and their primary biological impacts: A review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 199, 115991

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|