Continental shelf habitat

This article describes the habitat of the continental shelf. It is one of the sub-categories within the section dealing with biodiversity of marine habitats and ecosystems. It gives an introduction to the characteristics, processes such as sedimentation and biota.

Contents

Introduction

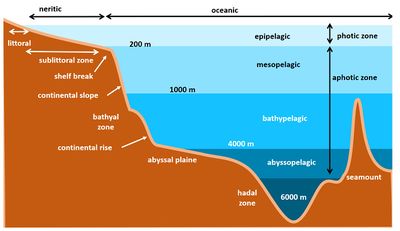

The continental shelf is a submarine extension of the adjacent continent. It is the shallow margin of deep ocean basins that extends from the upper continental slope to the shoreline. At the ocean side it is terminated by a pronounced change in bottom slope, called shelf break. The average slope of the continental shelf is generally very gentle, less than 1 degree. The average depth is about 150 m and it has an average width of 70 km. Individual shelves have widely varying widths ranging from more than 1000 km in the Arctic Ocean to a few kilometers at some places along the Pacific coast of North and South America. The water body on the continental shelf is called neritic zone. Beyond the shelf break is the much steeper continental slope. At the base of this slope is the continental rise which finally merges into the deep ocean floor, the abyssal plain. The continental shelf, slope and rise are part of the continental margin. This is the transition zone between the continental and the oceanic crust.

The continental shelf is one of the most productive parts of the ocean. Although shelf seas cover only 7.6% of the surface of the world's oceans, they provide 15-30% of the oceanic primary production (Yool and Fashman, 2001[2]). Larvae of benthic coastal animals that are capable of swimming are abundant in the neritic waters. A highly productive ecosystem on the continental shelf is the kelp forest.

Examples of large shelf seas are the Baltic and North Sea, Yellow and East China, Hudson Bay, Bering Sea,…

Hydro-sedimentary shelf processes

Energy for eroding and transporting shelf sediments is provided by tides and wind-generated waves and currents. Waves are the dominant process affecting the seabed in the shallow nearshore zone of the continental shelf where depths are less than 50 m (generally even less than 20 m). Tidal currents dominate in deeper water, often modulated by circulating currents related to seabed topography (small scale) or driven by the wind (large scale). For more details, see the articles Shelf sea exchange with the ocean, Ocean and shelf tides, Tidal motion in shelf seas, Sand ridges in shelf seas. The wave-dominated processes in the nearshore zone, in particular on the shoreface, play an important role for accretion or erosion of the coast (see e.g. Shoreface profile). In this zone, the seabed usually consists of coarser sediment (sand or gravel) because fine sediment is stirred up by wave action and transported to deeper water. Exceptions are the mud coasts where sediment supply mainly consists of very fine sediment. However, a transition from coarser to finer bottom sediments from shallower to deeper waters is the more usual situation, see the articles Characteristics of sedimentary shores and Coastal and marine sediments.

Biota

The neritic waters contain a rich community of organisms. The number and types of organisms that can live on the continental shelf are closely related to the types and characteristics of the sediments. Rivers are the main suppliers of nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, silica, calcium to the coastal seas; these nutrients are essential to marine life. At some ocean margins, nutrients can also reach the continental shelf by upwelling currents. Fast nutrient cycling by benthic microorganisms is a major reason for the high productivity of the continental shelves (see the article Nutrient conversion in the marine environment).

Two types of benthic communities can be distinguished, related to the characteristics of the substrate: the soft-bottom communities and the hard-bottom communities

- Hard-bottom communities occur in areas with strong currents. Because of the strong flows, the bottom consists of coarse sediments like gravel, rocks and sand. This is a less suitable habitat for burrowing and interstitial organisms because of the frequently shifting seabed sediments. Food carried along by the flow makes it a suitable area for sedentary or sessile filter-feeders or suspension-feeders. Sponges, anemones and colonial cnidarians (Hydrozoa) can attach to coarse sediments or other hardbottom elements. Due to the uneven surfaces of the substrate, a large number of niches are created. This, along with the extensive growth of seaweed, allows the growth of a rich benthic fauna.

Hyrdozoa Actinia equine[3]. |

Sponge Polymastia boletiformis[4]. |

Hydrozoa Tabularia indivisa [5]. |

- Soft-bottom communities occur in areas with weak currents. The seabed consists of fine sediments (fine sand, silt, mud). This is a suitable habitat for burrowing organisms like polychaete worms, amphipods and bivalves. Most of these organisms are deposit-feeders, feeding on particles of organic matter in the sediment. Filter-feeders are not abundant because there is less suspended matter in the water and the fine sediments obstruct the filtering structures.

Tubeworm Lanice conchilega [6]. |

Bivalves [7]. |

Amphipod Onisimus edwardsi[8] |

Sediments are usually not homogeneously distributed over the continental shelf. This causes an unequal distribution of benthic organisms called patchiness.

The main food source for the benthic community is detritus, originating from the water above. It consists of fecal pellets, dead organisms and organic debris. There are several ways to capture detritus such as tentacles, filter apparatus, scraping and cilia.

The water column or the neritic zone is dominated by plankton consisting of plants (phytoplankton), animals (zooplankton), bacteria, viruses, eggs and larvae. Among the most abundant types of phytoplankton are diatoms and dinoflagellates. They obtain energy through photosynthesis and need nutrients and sunlight to produce oxygen and organic matter – so-called primary production. Sunlight is usually not a limiting factor in the neritic zone, because it is a shallow zone and light penetrates deep enough for the phytoplankton to use it. However, light can be a limiting factor in alongshore turbid river plumes, see the article Which resource limits coastal phytoplankton growth/ abundance: underwater light or nutrients?. Seasonal changes in water temperature, salinity and nutrient input creates a regular succession of phytoplankton species in the temperate and polar seas. Zooplankton is dominated by copepods, larvae, protozoa, crustaceans and jellyfish and feeds on the phytoplankton by grazing. Plankton is not evenly distributed in the water and forms patches or aggregates in dense clusters.

Nekton are organisms such as larvae, mollusks, crustaceans, that can swim. They can avoid unfavorable conditions, search actively for food and breeding grounds. Like plankton, nekton is often aggregated in schools or clusters. They act like one unit and all the members are of about the same size. The benefit for the species is that they reduce the risk of being captured by predators. [9][10]

Further details on primary production and biota can be found in the articles Marine Plankton and Algal bloom dynamics.

Legal aspect

In the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS 1982), the definition of the continental shelf is: ‘The continental shelf of a coastal State comprises the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin or to the distance of 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured where the outer edge of the continental margin does not extend up to that distance.’

The coastal State has sovereign rights for exploring and exploiting natural resources at its part of the continental shelf. These natural resources are minerals and other non-living resources of the seabed and subsoil. Sedentary organisms are also included in the natural resources. The rights of the State are not applicable to the water and the air above it. [11]

The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), that extends up to 200 miles from the coastline, generally coincides mostly or entirely with the continental shelf. In the EEZ, states have sovereign rights for exploration, exploitation and management of all living and non-living resources.

A more complete overview is given in Legislation for the sea.

Related articles

- Shelf sea exchange with the ocean

- Coriolis and tidal motion in shelf seas

- Ocean and shelf tides

- Coastal and marine sediments

- Nutrient conversion in the marine environment

- Marine Plankton

- Algal bloom dynamics

References

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continental_shelf

- ↑ Yool, A. and Fashman, M.J.R. 2001. A study of the "continental flat pump" in a general model of circulation in the open ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 15 (4): 831-844

- ↑ http://www.marbef.org - Decleer M.

- ↑ http://www.marbef.org - Emblow C.S.

- ↑ http://www.marbef.org - Norro A.

- ↑ http://www.marbef.org - Decleer M.

- ↑ http://www.marbef.org - Nuyttens F.

- ↑ http://www.marbef.org – Legezynska.

- ↑ Karleskint G. 1998. Introduction to marine biology. Harcourt Brace College Publishers. p.378

- ↑ Pinet P.R. 1998.Invitation to Oceanography. Jones and Barlett Publishers. p. 508

- ↑ http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/closindx.htm

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|