Difference between revisions of "Wave set-up"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | |||

{{Definition|title= Wave set-up | {{Definition|title= Wave set-up | ||

|definition= Elevation of the mean water level at the shoreline due to wave breaking in the surf zone.}} | |definition= Elevation of the mean water level at the shoreline due to wave breaking in the surf zone.}} | ||

| Line 5: | Line 6: | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

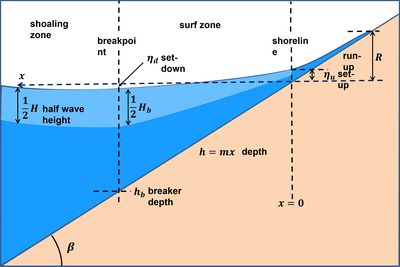

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:SetupRunup.jpg|thumb|400px|left|Fig. 1. Definition sketch wave set-down, wave set-up and wave run-up.]] |

Wave transformation in shallow water generates changes in the mean water level, called set-up for an upward change and set-down for a downward change. | Wave transformation in shallow water generates changes in the mean water level, called set-up for an upward change and set-down for a downward change. | ||

| − | The changes in mean sea level are related to the so-called [[ | + | The changes in mean sea level are related to the so-called [[radiation stress]]. The radiation stress is defined as the flow of momentum due to wave orbital motions. Gradients in the radiation stress induce an effective momentum transfer from wave motion to steady motion that takes place when the wave amplitude changes along the direction of propagation (see appendix). Wave set-down <math>\eta_d</math> occurs in the shoaling zone where the wave amplitude increases; wave wet-up <math>\eta_u</math> occurs in the surf zone where the wave amplitude decreases. Wave breaking is the major process in the surf zone responsible for wave energy dissipation and wave amplitude decay (see [[Breaker index]]). Analytical expressions of the wave set-down at the breakpoint and the wave set-up at the shoreline can be derived for a monochromatic wave, see [[Shallow-water wave theory#Wave set-down and set-up]]: |

| − | <math>\ | + | <math>\eta_u \approx -\frac{\gamma}{16} H_b , \qquad \eta_u \approx \eta_d +\frac{3 \gamma}{8} H_b \approx \frac{5 \gamma}{16} H_b, \qquad (1)</math> |

| − | + | Symbols: <math>H=</math> wave height, <math>h=</math> water depth, <math>\gamma = H_b/h_b =</math> [[breaker index]] (values in the range 0.5-1.2), <math>H_b=</math> wave height at the breakpoint, <math>h_b=</math> depth at the breakpoint (see Fig. 1). | |

| − | Besides monochromatic waves and applicability of shallow-water wave theory, other assumptions are: | + | Eq.(1) is based on the assumption of fully saturated depth-limited wave breaking, <math>\; H(x)/h(x)=\gamma \;</math> throughout the surf zone. |

| − | * a constant shoreface seabed slope <math> | + | |

| + | The strong simplifying assumptions that underly Eq. (1) limit its practical usefulness. Besides monochromatic waves and applicability of shallow-water wave theory, other assumptions are: | ||

| + | * a constant shoreface seabed slope <math>\tan\beta \approx \beta </math>, i.e. depth <math>h(x) = \beta \, x</math>; | ||

* shallow water, <math>2kh_b < 1</math> (<math>k=2 \pi / L</math> is the wave number); | * shallow water, <math>2kh_b < 1</math> (<math>k=2 \pi / L</math> is the wave number); | ||

| − | |||

* wave skewness and asymmetry can be ignored; | * wave skewness and asymmetry can be ignored; | ||

| − | * roller energy of breaking waves can be ignored; | + | * [[#Effect of the surface roller|roller energy]] of breaking waves can be ignored; |

* no momentum loss through dissipation at the seabed. | * no momentum loss through dissipation at the seabed. | ||

| + | Numerical modeling shows that neglecting momentum dissipation at the seabed (mainly momentum dissipation related to the undertow current) and neglecting dissipation of [[#Effect of the surface roller|roller energy]] yield an underprediction of the wave set-up<ref>Apotsos, A., Raubenheimer, B., Elgar, S., Guza, R.T. and Smith, J.A. 2007. Effects of wave rollers and bottom stress on wave setup. J. Geophysical Research 112, C02003</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In practice, empirical formulas derived from field and laboratory measurements are often used for determining the wave set-up. Many different formulas can be found in the literature<ref>Gomes da Silva, P., Coco, G., Garnier, R. and Klein, A.H.F. 2020. On the prediction of runup, setup and swash on beaches. Earth-Science Reviews 204, 103148</ref>. Most of these formulas relate the wave set-up to the offshore significant wave height <math>H_s</math>, the deep-water wave length <math>L = g T^2 \ /2 \pi</math> and the average surf zone bed slope <math>\beta</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several field measurements <ref>Guza, R.T. and Thornton, E.B. 1981. Wave set-up on a natural beach. J. Geophys. Res. 86: 4133–4137</ref><ref name=R1>Raubenheimer, B., Guza, R.T.and Elgar, S. 2001. Field observations of wave-driven setdown and setup. J. Geophys. Res. 106: 4629–4638</ref><ref>Atkinson, A. L., Power, H. E., Moura, T., Hammond, T., Callaghan, D. P. and Baldock, T. E. 2017. Assessment of runup predictions by empirical models on non‐truncated beaches on the south‐east Australian coast. Coastal Engineering 119: 15–31</ref> report values compatible with Eq. (1): | ||

| − | + | <math>\eta_u \approx 0.16 H_s . \qquad (2)</math> | |

| − | + | A popular formula for the wave set-up is<ref>Holman, R.A. and Sallenger, A.H. 1985. Setup and swash on a natural beach. J. Geophys. Res. 90: 945–953</ref><ref>Stockdon, H.F., Holman, R.A., Howd, P.A. and Sallenger, A.H. 2006. Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coast. Eng. 53: 573–588</ref><ref>Medellín, G., Brinkkemper, J.A., Torres-Freyermuth, A., Appendini, C.M., Mendoza, E.T. and Salles, P. 2016. Run-up parameterization and beach vulnerability assessment on a barrier island: a downscaling approach. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 16: 167–180</ref> | |

| − | <math>\eta_u = C \, | + | <math>\eta_u= C \, H_s \, \xi = C \, \beta \, \sqrt{H_s\, L}, \qquad (3)</math> |

| − | where <math>\xi= | + | where <math>\xi= \beta / \sqrt{H_s/L}</math> is the [[surf similarity parameter]] . The constant <math>C</math> can take values in the range 0.15 – 0.4. |

| − | Other empirical formulas differ from Eq. ( | + | Other empirical formulas differ from Eq. (3) especially regarding the dependence on the surf zone slope <math>\beta</math>, either by no dependence on <math>\beta</math><ref>Hanslow, D.J. and Nielsen, P. 1992. Wave setup on beaches and in river entrances. In: Proc. of the 23rd International Conference on Coastal Engineering. Venice, Italy, pp. 240–252</ref> or by an inverse relationship with <math>\beta</math>. <ref name=R1>Raubenheimer, B., Guza, R.T. and Elgar, S. 2001. Field observations of wave-driven setdown and setup. J. Geophys. Res. 106: 4629–4638</ref><ref>Didier, D., Caulet, C., Bandet, M., Bernatchez, P., Dumont, D., Augereau, E., Floc’h, F. and Delacourt, C. 2020. Wave runup parameterization for sandy, gravel and platform beaches in a fetch-limited, large estuarine system. Continental Shelf Research 192: 104024</ref> |

| − | The great diversity of empirical formulas and associated values for the wave set-up illustrates the limitations inherent to simple parameterizations of the shoreface. The shoreface bathymetry is highly variable and differs greatly among coasts, even among nearby locations. Complex bathymetries are ubiquitous due to the presence of [[nearshore sandbars]] and other [[rhythmic shoreline features]]. | + | The great diversity of empirical formulas and associated values for the wave set-up illustrates the limitations inherent to simple parameterizations of the shoreface. The shoreface bathymetry is highly variable and differs greatly among coasts, even among nearby locations. Complex bathymetries are ubiquitous due to the presence of [[nearshore sandbars]] and other [[rhythmic shoreline features]]. Accurate estimates of the wave set-up require in-situ observations or detailed numerical models. |

==Related articles== | ==Related articles== | ||

:[[Shallow-water wave theory]] | :[[Shallow-water wave theory]] | ||

| + | :[[Undertow]] | ||

:[[Wave run-up]] | :[[Wave run-up]] | ||

:[[Breaker index]] | :[[Breaker index]] | ||

| + | :[[Shoreface profile]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Appendix: Wave set-up balance equations== | ||

| + | |||

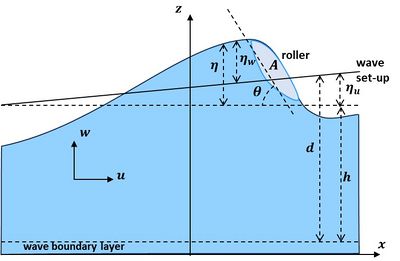

| + | [[File:SetUpSymbols.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Fig. 2. Definition sketch for the momentum balance equations.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | This appendix reproduces the equations from which the wave set-up <math>\eta_u</math> can be determined. We consider wave set-up driven by a surface wave <math>\eta_w (x,t)</math> incident normal to the shore of a longshore uniform coast. The incident wave from the far field is sinusoidal monochromatic, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\eta_w (x,t) = \dfrac{H}{2} \cos(\omega t – k x)</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Symbols are defined in Fig. 2, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>x=</math> shore-perpendicular onshore coordinate, <math>z=</math> vertical upward coordinate, <math>H=</math> wave height, <math>h=</math> still water depth, <math>g=</math> gravitational acceleration, <math>c \approx \sqrt{gh}=</math> wave celerity, <math>\omega=2 \pi /T = k c =</math> wave radial frequency, <math>k= 2 \pi /L=</math> wave number, <math>\big\langle … \big\rangle \, =</math>wave-averaged value (averaged over one or more wave cycles, encompassing the turbulence time scale), <math>\; u(x,z,t), \, w(x,z,t) \,=</math> horizontal, vertical velocity; <math>\; u_0 = <u>, \, w_0=<w></math>, <math>\; u_w, \, w_w \,=</math> horizontal, vertical wave orbital velocities, <math>\; u', \, w' \, =</math> turbulent velocity fluctuations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The velocities <math>u, \, w</math> and surface elevation <math>\eta</math> are decomposed as | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>u = u_0 + u_w + u' \, , \; w = w_0 + w_w + w' \, , \; \eta = \eta_u + \eta_w \, , \; \eta_u = \langle \eta \rangle . \qquad (1)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The momentum balance equation in the propagation direction is | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\dfrac{\partial u}{\partial t} + \dfrac{\partial u^2}{\partial x} + \dfrac{\partial w u}{\partial z} + \dfrac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial p}{\partial x} = 0 \, , \qquad (2)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>p=p(x,z,t)=</math> pressure. Integration over the depth and averaging over one or more wave cycles gives | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} \dfrac{\partial u}{\partial t} dz \Big\rangle + \Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} \dfrac{\partial u^2}{\partial x} dz \Big\rangle + \Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} \dfrac{\partial uw}{\partial z} dz \Big\rangle + \dfrac{1}{\rho} \Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} \dfrac{\partial p}{\partial x} dz \Big\rangle = \Big\langle \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \int_{-h}^{\eta} u^2 dz \Big\rangle + \dfrac{1}{\rho} \Big\langle \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \int_{-h}^{\eta} p dz \Big\rangle - \dfrac{1}{\rho } \Big\langle p_b \dfrac{dh}{dx} \Big\rangle+ \dfrac{1}{\rho } \Big\langle \tau_b - \tau_s \Big\rangle = 0 \, , \qquad (3)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>\tau_b= - \rho \big\langle u'_b w'_b \big\rangle \, , \; \tau_s = - \rho \big\langle u'_s w'_s \big\rangle </math> and subscripts <math>_b, \, _s</math> denote values at the seabed <math>z=-h</math> and the surface <math>z=\eta</math> respectively. For the permutation of integration and derivation in Eq. (3) we have used the surface and bottom boundary conditions which state that the surface and the seabed are streamlines: <math>\quad W_s=\dfrac{\partial \eta}{\partial t} + U_s \dfrac{\partial \eta}{\partial x} \; , \; W_b = - U_b\dfrac{dh}{dx} \, , </math> where <math>U = u_0+u_w \, , \, W = w_0+w_w</math>. The shear stress at the surface <math>\tau_s</math> is mainly due to the roller generated by wave breaking and shear stress at the seabed <math>\tau_b</math> is mainly due to turbulent momentum dissipation of the undertow. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The pressure at the seabed <math>\; p_b=\rho g (h+\eta) \; </math>, and thus <math>\quad \dfrac{1}{\rho} \Big\langle p_b \dfrac{dh}{dx} \Big\rangle = \dfrac{1}{2} g \dfrac{d}{dx} (h+\eta_u)^2 – g (h+\eta_u)\dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} \, . </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Substitution in Eq. (3) gives the wave set-up balance (see also [[Shallow-water wave theory#Radiation Stress (Momentum Flux)]]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math> \rho g d \dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} = - \dfrac{d}{dx} \Big(\int_{-h}^{trough} \rho u_0^2 dz \Big) - \dfrac{d S_{xx}}{dx} + \langle \tau_s \rangle - \langle \tau_b \rangle \, , \quad S_{xx} = \Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} ( \rho u_w^2 + p) dz \Big\rangle - \dfrac{1}{2} \rho g (h+\eta_u)^2 \, , \qquad (4)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>trough</math> indicates the surface level below the wave trough. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Effect of the surface roller==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:SpillingWave1.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Fig. 3. Spilling wave bore with onshore surfing roller. Photo credit Tim Haynes Flickr Creative Commons.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | We assume that the shear stress at the surface <math>\tau_s</math> is mainly related to the energy dissipation of the surface roller. The surface roller is a recirculating mixture of water and air generated at the breaking wave crest (Fig. 3). The breaking wave crest and associated roller are surfing as a bore towards the beach with celerity <math>c \approx \sqrt{gh}</math>. The water volume <math>A</math> of the roller (water volume per longshore meter) is estimated as being close to the square of the bore height (<math>A \sim H^2</math>)<ref name=D81>Duncan, J.H. 1981. An experimental investigation of breaking waves produced by a towed hydrofoil. Proc. R. Sot. London A, 377: 331-348</ref><ref>Engelund, F. 1981. A simple theory of weak hydraulic jumps. Progress Report No. 54, Institute of Hydrodynamics and Hydraulic Engineering, Technical University Denmark, pp. 29-32</ref>. The roller induces an additional onshore mass transport given by <math>\rho A c</math>. The energy <math>E_r</math> of the roller is estimated according to the relation | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>E_r = \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\rho A c^2}{L} = \dfrac{\rho A c}{2T} \, , \qquad (5) </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | which is the roller kinetic energy per wavelength <math>L=cT</math> (<math>T=</math> wave period). The shear stress <math>\tau_s</math> follows from considering the dynamic balance with the gravity force acting on the roller along the slope <math>\theta</math> (~10-15°) of the bore front (Fig. 2) <ref name=D81>Duncan, J.H. 1981. An experimental investigation of breaking waves produced by a towed hydrofoil. Proc. R. Sot. London A, 377: 331-348</ref>, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\langle \tau_s \rangle = \dfrac{\rho g A}{L} \sin \theta = \dfrac{2 g \sin \theta }{c^2} E_r \approx \dfrac{2 \sin \theta }{h} E_r \, . \qquad (6) </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The energy <math>D_{br}</math> [[Breaker index|dissipated by a breaking wave]] is first transferred to the roller and then dissipated by turbulent shearing to the underlying water body<ref name=RB>Reniers, A.J. and Battjes, J.A. 1997. A laboratory study of longshore currents over barred and non-barred beaches. Coastal Eng. 30: 1 – 22</ref>, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>a_r \dfrac{d}{dx} (c E_w) = - \dfrac{d}{dx} (2cE_r) - c \, \langle \tau_s \rangle \, , \quad \dfrac{d}{dx} (c E_w) \approx - \rho g \dfrac{H^3}{4 h T} \, , \qquad (7) </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>E_w = \rho g \langle \eta_w^2 \rangle</math> is the wave energy and <math>a_r</math> the fraction of the wave energy that is dissipated to the roller (estimated at about 0.6-0.7)<ref>Chen, J., Raubenheimer, B. and Elgar, S. 2024. Wave and roller transformation | ||

| + | over barred bathymetry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 129, e2023JC020413</ref>. The roller energy <math>E_r</math> can be estimated by solving this differential equation with the condition <math>E_r=0</math> seaward of the surf zone<ref>Lippmann, T.C., Brookins, A.H. and Thornton, E.B. 1996. Wave energy transformation on natural profiles. Coastal Engineering 27: 1-20</ref><ref name=RB>Reniers, A.J. and Battjes, J.A. 1997. A laboratory study of longshore currents over barred and non-barred beaches. Coastal Eng. 30: 1 – 22</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Effect of the undertow==== | ||

| + | The bed shear stress <math>\tau_b</math> is mainly determined by the momentum dissipation of the mean current <math>u_0</math> ('undertow') driven by the radiation stress. Assuming an eddy viscosity description of the momentum dissipation in the wave boundary layer with eddy viscosity coefficient <math>K</math> we have | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\dfrac{1}{\rho} \langle \tau_b \rangle = K \dfrac{\partial u_0}{\partial z} |_{z=-h} \, . \qquad (8) </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[radiation stress]] <math>S_{xx}</math> mainly results from breaker-induced wave dissipation and can be approximated as (see [[Breaker index]]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\dfrac{d}{dx} S_{xx} \approx - \dfrac{3}{2} \dfrac{dE_w}{dx} \approx \dfrac{3c}{8T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 \, .</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The undertow current <math>u_0</math> can be determined from the balance equations shown in the appendix of the article [[Undertow]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The wave set-up Eq. (4) thus becomes | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\rho g d \dfrac{d\eta_u }{dx} + \dfrac{d}{dx} \Big(\int_{-h}^{trough} \rho u_0^2 dz \Big) = \dfrac{3c}{8T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 + \dfrac{2 \sin \theta }{h} E_r - \langle \tau_b \rangle \, . \qquad (9) </math> | ||

| + | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{author | ||

| + | |AuthorID=120 | ||

| + | |AuthorFullName=Job Dronkers | ||

| + | |AuthorName=Dronkers J}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Beaches]] | ||

Latest revision as of 12:46, 23 April 2025

Definition of Wave set-up:

Elevation of the mean water level at the shoreline due to wave breaking in the surf zone.

This is the common definition for Wave set-up, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

Contents

Notes

Wave transformation in shallow water generates changes in the mean water level, called set-up for an upward change and set-down for a downward change. The changes in mean sea level are related to the so-called radiation stress. The radiation stress is defined as the flow of momentum due to wave orbital motions. Gradients in the radiation stress induce an effective momentum transfer from wave motion to steady motion that takes place when the wave amplitude changes along the direction of propagation (see appendix). Wave set-down [math]\eta_d[/math] occurs in the shoaling zone where the wave amplitude increases; wave wet-up [math]\eta_u[/math] occurs in the surf zone where the wave amplitude decreases. Wave breaking is the major process in the surf zone responsible for wave energy dissipation and wave amplitude decay (see Breaker index). Analytical expressions of the wave set-down at the breakpoint and the wave set-up at the shoreline can be derived for a monochromatic wave, see Shallow-water wave theory#Wave set-down and set-up:

[math]\eta_u \approx -\frac{\gamma}{16} H_b , \qquad \eta_u \approx \eta_d +\frac{3 \gamma}{8} H_b \approx \frac{5 \gamma}{16} H_b, \qquad (1)[/math]

Symbols: [math]H=[/math] wave height, [math]h=[/math] water depth, [math]\gamma = H_b/h_b =[/math] breaker index (values in the range 0.5-1.2), [math]H_b=[/math] wave height at the breakpoint, [math]h_b=[/math] depth at the breakpoint (see Fig. 1).

Eq.(1) is based on the assumption of fully saturated depth-limited wave breaking, [math]\; H(x)/h(x)=\gamma \;[/math] throughout the surf zone.

The strong simplifying assumptions that underly Eq. (1) limit its practical usefulness. Besides monochromatic waves and applicability of shallow-water wave theory, other assumptions are:

- a constant shoreface seabed slope [math]\tan\beta \approx \beta [/math], i.e. depth [math]h(x) = \beta \, x[/math];

- shallow water, [math]2kh_b \lt 1[/math] ([math]k=2 \pi / L[/math] is the wave number);

- wave skewness and asymmetry can be ignored;

- roller energy of breaking waves can be ignored;

- no momentum loss through dissipation at the seabed.

Numerical modeling shows that neglecting momentum dissipation at the seabed (mainly momentum dissipation related to the undertow current) and neglecting dissipation of roller energy yield an underprediction of the wave set-up[1].

In practice, empirical formulas derived from field and laboratory measurements are often used for determining the wave set-up. Many different formulas can be found in the literature[2]. Most of these formulas relate the wave set-up to the offshore significant wave height [math]H_s[/math], the deep-water wave length [math]L = g T^2 \ /2 \pi[/math] and the average surf zone bed slope [math]\beta[/math].

Several field measurements [3][4][5] report values compatible with Eq. (1):

[math]\eta_u \approx 0.16 H_s . \qquad (2)[/math]

A popular formula for the wave set-up is[6][7][8]

[math]\eta_u= C \, H_s \, \xi = C \, \beta \, \sqrt{H_s\, L}, \qquad (3)[/math]

where [math]\xi= \beta / \sqrt{H_s/L}[/math] is the surf similarity parameter . The constant [math]C[/math] can take values in the range 0.15 – 0.4.

Other empirical formulas differ from Eq. (3) especially regarding the dependence on the surf zone slope [math]\beta[/math], either by no dependence on [math]\beta[/math][9] or by an inverse relationship with [math]\beta[/math]. [4][10]

The great diversity of empirical formulas and associated values for the wave set-up illustrates the limitations inherent to simple parameterizations of the shoreface. The shoreface bathymetry is highly variable and differs greatly among coasts, even among nearby locations. Complex bathymetries are ubiquitous due to the presence of nearshore sandbars and other rhythmic shoreline features. Accurate estimates of the wave set-up require in-situ observations or detailed numerical models.

Related articles

Appendix: Wave set-up balance equations

This appendix reproduces the equations from which the wave set-up [math]\eta_u[/math] can be determined. We consider wave set-up driven by a surface wave [math]\eta_w (x,t)[/math] incident normal to the shore of a longshore uniform coast. The incident wave from the far field is sinusoidal monochromatic,

[math]\eta_w (x,t) = \dfrac{H}{2} \cos(\omega t – k x)[/math].

Symbols are defined in Fig. 2,

[math]x=[/math] shore-perpendicular onshore coordinate, [math]z=[/math] vertical upward coordinate, [math]H=[/math] wave height, [math]h=[/math] still water depth, [math]g=[/math] gravitational acceleration, [math]c \approx \sqrt{gh}=[/math] wave celerity, [math]\omega=2 \pi /T = k c =[/math] wave radial frequency, [math]k= 2 \pi /L=[/math] wave number, [math]\big\langle … \big\rangle \, =[/math]wave-averaged value (averaged over one or more wave cycles, encompassing the turbulence time scale), [math]\; u(x,z,t), \, w(x,z,t) \,=[/math] horizontal, vertical velocity; [math]\; u_0 = \lt u\gt , \, w_0=\lt w\gt [/math], [math]\; u_w, \, w_w \,=[/math] horizontal, vertical wave orbital velocities, [math]\; u', \, w' \, =[/math] turbulent velocity fluctuations.

The velocities [math]u, \, w[/math] and surface elevation [math]\eta[/math] are decomposed as

[math]u = u_0 + u_w + u' \, , \; w = w_0 + w_w + w' \, , \; \eta = \eta_u + \eta_w \, , \; \eta_u = \langle \eta \rangle . \qquad (1)[/math]

The momentum balance equation in the propagation direction is

[math]\dfrac{\partial u}{\partial t} + \dfrac{\partial u^2}{\partial x} + \dfrac{\partial w u}{\partial z} + \dfrac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial p}{\partial x} = 0 \, , \qquad (2)[/math]

where [math]p=p(x,z,t)=[/math] pressure. Integration over the depth and averaging over one or more wave cycles gives

[math]\Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} \dfrac{\partial u}{\partial t} dz \Big\rangle + \Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} \dfrac{\partial u^2}{\partial x} dz \Big\rangle + \Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} \dfrac{\partial uw}{\partial z} dz \Big\rangle + \dfrac{1}{\rho} \Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} \dfrac{\partial p}{\partial x} dz \Big\rangle = \Big\langle \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \int_{-h}^{\eta} u^2 dz \Big\rangle + \dfrac{1}{\rho} \Big\langle \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \int_{-h}^{\eta} p dz \Big\rangle - \dfrac{1}{\rho } \Big\langle p_b \dfrac{dh}{dx} \Big\rangle+ \dfrac{1}{\rho } \Big\langle \tau_b - \tau_s \Big\rangle = 0 \, , \qquad (3)[/math]

where [math]\tau_b= - \rho \big\langle u'_b w'_b \big\rangle \, , \; \tau_s = - \rho \big\langle u'_s w'_s \big\rangle [/math] and subscripts [math]_b, \, _s[/math] denote values at the seabed [math]z=-h[/math] and the surface [math]z=\eta[/math] respectively. For the permutation of integration and derivation in Eq. (3) we have used the surface and bottom boundary conditions which state that the surface and the seabed are streamlines: [math]\quad W_s=\dfrac{\partial \eta}{\partial t} + U_s \dfrac{\partial \eta}{\partial x} \; , \; W_b = - U_b\dfrac{dh}{dx} \, , [/math] where [math]U = u_0+u_w \, , \, W = w_0+w_w[/math]. The shear stress at the surface [math]\tau_s[/math] is mainly due to the roller generated by wave breaking and shear stress at the seabed [math]\tau_b[/math] is mainly due to turbulent momentum dissipation of the undertow.

The pressure at the seabed [math]\; p_b=\rho g (h+\eta) \; [/math], and thus [math]\quad \dfrac{1}{\rho} \Big\langle p_b \dfrac{dh}{dx} \Big\rangle = \dfrac{1}{2} g \dfrac{d}{dx} (h+\eta_u)^2 – g (h+\eta_u)\dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} \, . [/math]

Substitution in Eq. (3) gives the wave set-up balance (see also Shallow-water wave theory#Radiation Stress (Momentum Flux))

[math] \rho g d \dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} = - \dfrac{d}{dx} \Big(\int_{-h}^{trough} \rho u_0^2 dz \Big) - \dfrac{d S_{xx}}{dx} + \langle \tau_s \rangle - \langle \tau_b \rangle \, , \quad S_{xx} = \Big\langle \int_{-h}^{\eta} ( \rho u_w^2 + p) dz \Big\rangle - \dfrac{1}{2} \rho g (h+\eta_u)^2 \, , \qquad (4)[/math]

where [math]trough[/math] indicates the surface level below the wave trough.

Effect of the surface roller

We assume that the shear stress at the surface [math]\tau_s[/math] is mainly related to the energy dissipation of the surface roller. The surface roller is a recirculating mixture of water and air generated at the breaking wave crest (Fig. 3). The breaking wave crest and associated roller are surfing as a bore towards the beach with celerity [math]c \approx \sqrt{gh}[/math]. The water volume [math]A[/math] of the roller (water volume per longshore meter) is estimated as being close to the square of the bore height ([math]A \sim H^2[/math])[11][12]. The roller induces an additional onshore mass transport given by [math]\rho A c[/math]. The energy [math]E_r[/math] of the roller is estimated according to the relation

[math]E_r = \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\rho A c^2}{L} = \dfrac{\rho A c}{2T} \, , \qquad (5) [/math]

which is the roller kinetic energy per wavelength [math]L=cT[/math] ([math]T=[/math] wave period). The shear stress [math]\tau_s[/math] follows from considering the dynamic balance with the gravity force acting on the roller along the slope [math]\theta[/math] (~10-15°) of the bore front (Fig. 2) [11],

[math]\langle \tau_s \rangle = \dfrac{\rho g A}{L} \sin \theta = \dfrac{2 g \sin \theta }{c^2} E_r \approx \dfrac{2 \sin \theta }{h} E_r \, . \qquad (6) [/math]

The energy [math]D_{br}[/math] dissipated by a breaking wave is first transferred to the roller and then dissipated by turbulent shearing to the underlying water body[13],

[math]a_r \dfrac{d}{dx} (c E_w) = - \dfrac{d}{dx} (2cE_r) - c \, \langle \tau_s \rangle \, , \quad \dfrac{d}{dx} (c E_w) \approx - \rho g \dfrac{H^3}{4 h T} \, , \qquad (7) [/math]

where [math]E_w = \rho g \langle \eta_w^2 \rangle[/math] is the wave energy and [math]a_r[/math] the fraction of the wave energy that is dissipated to the roller (estimated at about 0.6-0.7)[14]. The roller energy [math]E_r[/math] can be estimated by solving this differential equation with the condition [math]E_r=0[/math] seaward of the surf zone[15][13].

Effect of the undertow

The bed shear stress [math]\tau_b[/math] is mainly determined by the momentum dissipation of the mean current [math]u_0[/math] ('undertow') driven by the radiation stress. Assuming an eddy viscosity description of the momentum dissipation in the wave boundary layer with eddy viscosity coefficient [math]K[/math] we have

[math]\dfrac{1}{\rho} \langle \tau_b \rangle = K \dfrac{\partial u_0}{\partial z} |_{z=-h} \, . \qquad (8) [/math]

The radiation stress [math]S_{xx}[/math] mainly results from breaker-induced wave dissipation and can be approximated as (see Breaker index)

[math]\dfrac{d}{dx} S_{xx} \approx - \dfrac{3}{2} \dfrac{dE_w}{dx} \approx \dfrac{3c}{8T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 \, .[/math]

The undertow current [math]u_0[/math] can be determined from the balance equations shown in the appendix of the article Undertow.

The wave set-up Eq. (4) thus becomes

[math]\rho g d \dfrac{d\eta_u }{dx} + \dfrac{d}{dx} \Big(\int_{-h}^{trough} \rho u_0^2 dz \Big) = \dfrac{3c}{8T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 + \dfrac{2 \sin \theta }{h} E_r - \langle \tau_b \rangle \, . \qquad (9) [/math]

References

- ↑ Apotsos, A., Raubenheimer, B., Elgar, S., Guza, R.T. and Smith, J.A. 2007. Effects of wave rollers and bottom stress on wave setup. J. Geophysical Research 112, C02003

- ↑ Gomes da Silva, P., Coco, G., Garnier, R. and Klein, A.H.F. 2020. On the prediction of runup, setup and swash on beaches. Earth-Science Reviews 204, 103148

- ↑ Guza, R.T. and Thornton, E.B. 1981. Wave set-up on a natural beach. J. Geophys. Res. 86: 4133–4137

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Raubenheimer, B., Guza, R.T.and Elgar, S. 2001. Field observations of wave-driven setdown and setup. J. Geophys. Res. 106: 4629–4638 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "R1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Atkinson, A. L., Power, H. E., Moura, T., Hammond, T., Callaghan, D. P. and Baldock, T. E. 2017. Assessment of runup predictions by empirical models on non‐truncated beaches on the south‐east Australian coast. Coastal Engineering 119: 15–31

- ↑ Holman, R.A. and Sallenger, A.H. 1985. Setup and swash on a natural beach. J. Geophys. Res. 90: 945–953

- ↑ Stockdon, H.F., Holman, R.A., Howd, P.A. and Sallenger, A.H. 2006. Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coast. Eng. 53: 573–588

- ↑ Medellín, G., Brinkkemper, J.A., Torres-Freyermuth, A., Appendini, C.M., Mendoza, E.T. and Salles, P. 2016. Run-up parameterization and beach vulnerability assessment on a barrier island: a downscaling approach. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 16: 167–180

- ↑ Hanslow, D.J. and Nielsen, P. 1992. Wave setup on beaches and in river entrances. In: Proc. of the 23rd International Conference on Coastal Engineering. Venice, Italy, pp. 240–252

- ↑ Didier, D., Caulet, C., Bandet, M., Bernatchez, P., Dumont, D., Augereau, E., Floc’h, F. and Delacourt, C. 2020. Wave runup parameterization for sandy, gravel and platform beaches in a fetch-limited, large estuarine system. Continental Shelf Research 192: 104024

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Duncan, J.H. 1981. An experimental investigation of breaking waves produced by a towed hydrofoil. Proc. R. Sot. London A, 377: 331-348

- ↑ Engelund, F. 1981. A simple theory of weak hydraulic jumps. Progress Report No. 54, Institute of Hydrodynamics and Hydraulic Engineering, Technical University Denmark, pp. 29-32

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Reniers, A.J. and Battjes, J.A. 1997. A laboratory study of longshore currents over barred and non-barred beaches. Coastal Eng. 30: 1 – 22

- ↑ Chen, J., Raubenheimer, B. and Elgar, S. 2024. Wave and roller transformation over barred bathymetry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 129, e2023JC020413

- ↑ Lippmann, T.C., Brookins, A.H. and Thornton, E.B. 1996. Wave energy transformation on natural profiles. Coastal Engineering 27: 1-20

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|