Shoreline management

Definition of Shoreline management:

The act of dealing – in a planned way – with actual and potential coastal erosion and its relation to planned or existing development activities on the coast. The objectives of Shoreline Management are [1]:

This is the common definition for Shoreline management, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

This article provides an introduction to modern shoreline management, in the context of Integrated Coastal Zone Management. It describes general principles for drafting Shoreline Management Plans. Shoreline Management Planning in the UK is discussed as an example. Large parts of this article are taken from the coastal engineering handbook of Reeve, Chadwick and Fleming (2018)[2].

Contents

- 1 Pressures on the Coast

- 2 Local Approaches

- 3 Strategic Approaches

- 4 Recommendations

- 5 Practical guidelines for shore protection

- 6 Early Strategic Approach in the UK (Case Study)

- 7 Current UK SMP Approach(2011)

- 8 Adaptation to climate change

- 9 An example of adaptation to climate change in Barbados (Case Study)

- 10 Related articles

- 11 Further reading

- 12 References

Pressures on the Coast

Coastal areas have always been a popular place for recreation, habitation and commerce. Typical features include ports, marinas, fishing harbours, roads, railways, power stations, agriculture, recreational resorts, residential property, agriculture and a wide variety of natural habitats. In many parts of the world land immediately adjacent to the sea is significantly more valuable that elsewhere. It is therefore not surprising that that the coastal boundary is has been subject to both reclamation and protection in response to economic pressures. In many areas of the world there are soft eroding cliffs that experience erosion as well as low lying coastal plains that are vulnerable to both erosion and flooding due to the action of the sea. This coupled with gradually rising sea levels due to global warming has resulted in an increase in the shorelines around the world suffering from erosion. Moreover, the prospect of accelerating sea level rise and possible changes in the frequency and direction of storms presents a high degree of risk and uncertainty when it comes to considering the most appropriate design scenarios for coastal structures.

Global, regional and local issues such as sea level rise, the concentration of populations and tourism on the coast, and depletion and damage to valuable natural resources such as fisheries and wildlife, are making coastlines one of the most pressured and threatened environments in the world. Most of the world's major cities are at the coast, and more than 50% of the world's estimated 5.5 billion people live in coastal areas. It has been predicted that by 2020, 75% of the world's projected population of 8 billion could be living within 60 kilometres of the shoreline, the majority in developing nations.

This concentration of population at the coast is a result of a number of factors including:

- The diverse and productive renewable resources base in coastal areas which include fisheries, forests and fertile soils;

- Accessibility to maritime trade and transport routes through the construction of ports and harbours;

- Abundant and attractive recreational and tourism opportunities; and industrial investments such as power stations and oil/gas terminals;

- Increasing demands for residential property on or close to the coastal strip.

The demands made by this population concentration have caused problems such as:

- Over-exploitation of renewable resources like coastal fisheries, beyond sustainable yields;

- Degradation of coastal water and marine ecosystems from land-based pollution including sediment run-off, fertilizers and untreated sewage;

- Destruction of natural coastal habitats for construction or coastal aquaculture.

Coastal locations are also susceptible to a range of natural hazards such as storm surges, erosion and sea level change that can cause loss of life and property and damage to infrastructure, livestock and crops. Damage to the coastal infrastructure is often considered to be politically and economically unacceptable. However, in many circumstances it can no longer be assumed that defences should be maintained where they have previously existed. Through taking a strategic approach, there has been a significant change in the way that the design of coastal defences should be developed with the emphasis shifting from the provision of protection to managing the coastline in spatial scales that recognise the interactive nature of the processes that take place as well as over longer-term temporal scales. In doing so it is necessary to recognise that there is considerable uncertainty in defining all of the relevant parameters that can impact on the eventual outcome of adopting various policies so that management practices require a strategic approach that is largely based on risk analysis and continuous performance monitoring.

Local Approaches

Some design practices in the past, and in some places the present, might be classified as the ‘brute force’ approach. This is the principle that if a structure is big enough and strong enough it can withstand almost any of the conditions that it can be subject to with the exception of the most extreme events. However, this often takes no account of the morphological context in which the structure might exist. A further problem that seems to have persisted is that, whilst there have been significant advances in the appreciation of the interactions involved in regional coastal processes the physical areas of responsibility, and hence parochial interest, have been constrained to sub-areas of the coastal cell. In the event new works or repairs would be initiated as site-specific problems arose, sometimes as a result of ad-hoc monitoring. Interaction with adjacent sections of coastlines, and the constraint that they might impose would often only be considered in relation to the specific problem at the site. The result of this process would be that, whilst a particular problem might be solved with capital works, the wider implications of this action would not be addressed. Thus regional strategy, social planning and environmental management would not have been fully considered so that all the possible options could be explored. These would generally include measures to mitigate any potential downdrift erosion problems, preservation of natural habitats or recognition of alternative uses and enjoyment of the coastal environment.

The ad-hoc nature of this approach is unsatisfactory as it makes it extremely difficult to ensure that not only are schemes developed to be efficient and cost effective, but also natural process and natural resources are used to best effect in tandem with anthropological uses of the coastal area. The benefits of a more strategic approach to shoreline management should thus be easily appreciated.

Strategic Approaches

In many parts of the world, the idea of "Integrated Coastal Zone Management" (ICZM) is proposed as being a more satisfactory way forward. This is a process that goes beyond the traditional approach of planning and managing activities on an individual scheme basis. Instead, the aim is to focus on the combined effects of all activities taking place at the coast to seek suitable environmental and socio-economic outcomes. Sustainable use, with environmental considerations underlying decision making in all sectors of activity, provides the basis for this type of management. It is geared to dealing with the coastal environment as a whole - coastal land, the foreshore, and inshore waters - and is forward looking, as well as trying to resolve the problems of present day use of the coast.

Shoreline management is an important component of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). Principles of ICZM are summarised in the recommendations of the European Union on Integrated Coastal Zone Management and also discussed in The Integrated approach to Coastal Zone Management (ICZM). ICZM involves the comprehensive assessment, setting of objectives, planning and management of coastal systems and resources, taking into account traditional cultural and historical perspectives, cumulative impacts, and conflicting interests and uses. It is a continuous and evolutionary process for achieving sustainable development through participation of the public and private sectors and with the support and interest of local communities.

Recommendations

When focusing on shoreline management, the following recommendations are relevant.

- A precondition for a successful shoreline restoration project is that all the parties involved have some understanding of coastal morphological processes; they are then in a position to understand why the present situation has developed and why certain solutions may work and others will not.

- Consider the coastal area as a dynamic natural landscape. Make only interventions in the coastal processes and in the coastal landscape if other interests of society are more important than preserving the natural coastal resource.

- Appoint special sections of the coast for natural development.

- Demolish inexpedient old protection schemes and re-establish the natural coastal landscape where possible.

- Minimise the use of hard coastal protection schemes, give high priority to the quality of the natural coastal resource.

- Preserve the natural variation in the coastal landscapes.

- Restrict new development/housing close to the coastline in the open uninhabited coastal landscape.

- Maintain and improve public access to and along the beach, legally as well as in practice.

- Reduce pollution and enhance sustainable utilisation of coastal waters.

Practical guidelines for shore protection

Below, the general recommendations are elaborated into practical guidelines for shore protection, shore restoration and sea defence projects.

- Work with nature, for instance by re-establishing a starved coastal profile by nourishment and by utilising site-specific features, such as strengthening (semi-)hard promontories.

- Select a solution which fits the type of coastline and which fulfils as many of the goals set by the stakeholders and the authorities as possible. It may be impossible to fulfil all goals, as they are often conflicting and because of budget limitations. It should be made clear to all parties, which goals are fulfilled and which are not. The consultant must make it completely clear what the client can expect from the selected solution; this is especially important if the project has been adjusted to fit the available funds.

- Propose a funding distribution that reflects the fulfilment of the various goals, set by the parties involved.

- Allow protection measures only if valuable buildings/infrastructure are threatened.

- Choose a protection scheme that preserves sections of untouched dynamic landscape where possible, for example by applying appropriate vegetation.

- Use of a minimum number of hard structures required for achieving the protection objectives.

- Secure passage to and along the beach.

- Enhance the aesthetic appearance, e.g. by minimising the number of structures. Few and larger structures can be better than a lot of small structures.

- Preferably allow only projects which deal with an entire management unit/sediment cell and which secure maximum shore protection.

- Minimise maintenance requirements to a level that the owner(s) of the scheme is able to manage. A stand-alone nourishment solution may at first glance appear ideal, but it will normally not be ideal for the landowners, as recharge will be required at short intervals.

- Secure good local water quality and minimise the risk of trapping debris and seaweed.

- Secure safety for swimmers by avoiding structures generating dangerous rip currents. Avoid sheltered beaches (coves) as these give a false impression of safety for poor swimmers. Sheltered beaches may suffer from fine sediment trapping. If the water is too rough for swimming, a swimming pool, possibly in the form of a tidal pool, is a good solution.

- Provide good beach quality by securing that the beaches are exposed to waves, as wave action maintains attractive sandy beaches. This will of course limit the time that swimming is possible, but sheltered beaches often imply safety risks, poor beach quality and poor water quality.

- Be realistic and pragmatic, keeping in mind that the natural untouched coastline is utopia in highly developed areas. Create small attractive locations at otherwise strongly protected stretches if this is the only realistic possibility.

Early Strategic Approach in the UK (Case Study)

Formal shoreline management practices have been developing in the United Kingdom over the past twenty years or so. The Anglian Sea Defence Management Study (Fleming, 1989 [3], Townend et al, 1990[4]) was the forerunner to the development of shoreline management plans (SMP’s) around the coastline of England and Wales. The Anglian coast is some 750 kilometres in length and the initial analysis of the coastline was based on the collation of a number of factors considered to influence the choice of management policy as listed in Table 1. These were selected on the basis that they either:

- provided information on the direct influences and responses of the coast such as waves, coastal morphology, and rate of retreat or

- provided information on their implications with respect to the impact of accretion/erosion and any defence strategy that might be implemented.

This list is not exhaustive and other influences might be found to occur in particular circumstances.

| Main Variable | Significance |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | Changes in habitat; Drainage patterns and run-off. |

| Birds | Assessment of environmental impact. |

| Coastal movement | Indicate areas of high/low activity; Assist with forecasting future movements; Relationship to sediment budget. |

| Conservation sites | Special consideration to prevent undesirable changes. |

| Currents | Influences sediment movement on offshore zones, links nearshore processes with far field effects. |

| Ecology | A measure of shoreline (cliff, dune, saltmarsh) stability, shelter, relationship with rivers and estuaries; Assessment of environmental impact. |

| Fisheries | Changes in habitat; Potential environmental impact. |

| Industry | Coastal impact on processes and environment; Threat to habitats. |

| Morphology | Basic description of coastline; Physical significance (eg offshore banks dissipate wave energy, cliffs can provide a sediment supply etc.); Width of foreshore indicates plan effects; Slopes control form of incoming waves; Indicates nature of sediment transport; Represents sediment sources and sinks; Intertidal features indicate beach cycles and on-shore movement. |

| Rainfall | Influences groundwater levels and river discharges; Impact on sediment load in rivers; Impact on cliff stability. |

| Sediments | Determines mobility of material; Forensic evidence for sources of materials; Basis for sediment budget. |

| Temperature | Seasonal variations may contribute to erosion. |

| Water levels | Major effect on coastal processes; Controls extent of wave influence on shoreline; Relates to potential for hinterland flooding. |

| Water quality | Influences vegetation and hence shoreline stability; Impact on marine life and alteration of habitats; Density effects and transport regime. |

| Waves | Fundamental to potential for shoreline erosion and accretion; Influences height and movement of offshore banks; Primary cause of infrastructure damage; Linked to climate change. |

| Wind | Generates waves and storm surges; Governs subaerial erosion and deposition. |

The Anglian Sea Defence Management Project adopted an approach that involved collection of spatial and temporal data, such as shoreline position. These data were analysed using data mining techniques to provide insight into the behavioural trends of the coastline. Data were also supplemented by the use of numerical modelling of various coastal processes. The coastline was divided into management units which are sections of coastline that exhibit coherent characteristics in terms of baseline geology, natural processes, existing defences, foreshore type and land use. It was then attempted to link the coastal management strategy to the objectives that needed to be satisfied through consultation with a wide range of stakeholders. Shoreline policy options for the management units identified were simply described as:

- Maintain existing line

- Set back defence

- Retreat the defence line

- Advance or reclaim

On the face of it these options appear to be quite obvious and simplistic. However, it must be appreciated that a policy option selected on one section of coastline will invariably have an impact on the adjacent coastline and beyond. The first option applies to any existing line, which is being defended and will generally be preferred whenever there is a substantial investment in infrastructure on the coast. However, this option can be linked to a change in the standard of service of the defence. On an eroding coast set-back would be used to provide defences on the hinterland so that it is only necessary to defend against tidal inundation. The option could also be used to provide natural features ‘room to move’ (such as barrier beach and salt marsh systems), whilst retaining a level of defence against flooding. The retreat option was a managed withdrawal, allowing the coast to return to its natural state and could have been be an attractive option where the tidal floodplain was relatively narrow. It would also apply where no defence was to be provided on a naturally eroding coastline, but soft engineering expedients such as dune management, cliff drainage or beach management might be considered. Finally, the advance option allowed for the possibility of limiting low-lying exposure by suitable reclamation or the use of tidal barriers. The option that was chosen will be largely dependent on the existing infrastructure and erosion areas for any given length of coastline.

In order to implement any policy options it was proposed that various management options could be considered providing they were appropriate to the coastal classification. Those options were described as:

- Do nothing: let nature take its course

- Reinstate: beach renourishment, saltings regeneration, structural reconstruction etc.

- Modify: remove features or structures, structural alterations, stabilisation (cliffs/dunes/saltings) etc.

- Create: embayments, linear protection, intervention such as dredging, sand bypassing etc.

By defining policy options and management options for an entire coastline, the basis for a strategic management plan was established. It was recognised that, as actions based on this plan were to be undertaken, so aspects of the coastal characteristics would be modified and this, in time, was likely to alter the coastal classification.

The foregoing describes some of the formative basic principles behind the development of ‘shoreline management’ in the UK and is differentiated from ‘integrated coastal zone management’ which includes a very much wider range of considerations with respect to the use and sustainable development of the wider coastal zone. It is beyond the scope of this book to cover these wider issues

Current UK SMP Approach(2011)

The strategic approach to shoreline management in the United Kingdom has been driven and sponsored by the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). The overall objective can be stated as (Burgess, 2002[5]): To reduce risks to people and the developed and natural environment from flooding and coastal erosion by encouraging the provision of technically, environmentally and economically sound and sustainable defence measures. In this context sustainable management approaches are those which: …..take into account the relationships with other defences, developments and processes………. And which avoid as far as possible tying future generations into inflexible and expensive options for defence.

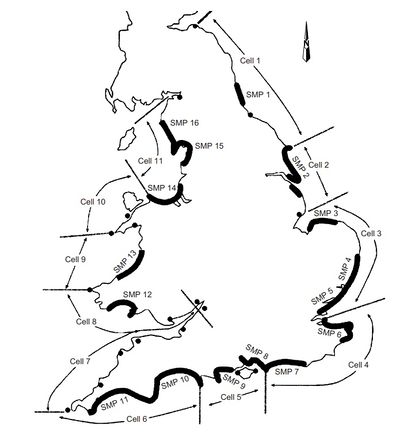

In order to assist in this process the coastline of England and Wales was initially divided into a number of primary coastal cells and sub-cells which were defined as relatively self-contained units with respect to the movement of beach material [6], see Figure 1. These are managed by groups that include representation from all of the authorities that have any statutory responsibility for coastline in the cell. The first round of SMPs to be developed provide the framework for defining the policy options that should be adopted in order to minimise the occurrence of flooding and coastal erosion in the context of sustainable development, whether related to the continuity of sediment transport processes or environmental conservation. At the same time the requirements of whatever legislation exists must be satisfied. The overall objectives of the shoreline management plan process are (Brampton, 2002[7]):

- To define, in general terms, the risks to people and the developed, historic and natural environment within the shoreline management plan area;

- To define the natural processes taking place in terms of forcing functions (e.g. waves, tides, currents etc) and response (e.g. sediment movement, shoreline movement etc.);

- To define the potential retreat or advance of the shoreline within the statutory planning horizon of 70 years;

- To consult and conciliate with all of the users of the coastline in the area;

- To identify the preferred policies for managing these risks over the next 50 years;

- To identify the consequences of implementing the preferred policies;

- To set out procedures for monitoring the effectiveness of the shoreline management plan policies;

- To ensure that future land use and development of the shoreline takes due account of the risks and preferred shoreline management plan policies.

SMP guidance has evolved quite rapidly over the past decade since the first edition of this book was published in 2004. DEFRA(2006) [8][9] published a two volume document titled ‘Shoreline management plan guidance’. This describes an SMP as a large-scale assessment of the risks associated with coastal processes and helps to reduce these risks to people and the developed, historic and natural environment. The strategy should aim to manage risks by using a range of methods which reflect both national and local priorities, to:

- Reduce the threat of flooding and erosion to people and their property; and

- Benefit the environment, society and the economy as far as possible, in line with the Government’s ‘sustainable development principles’.

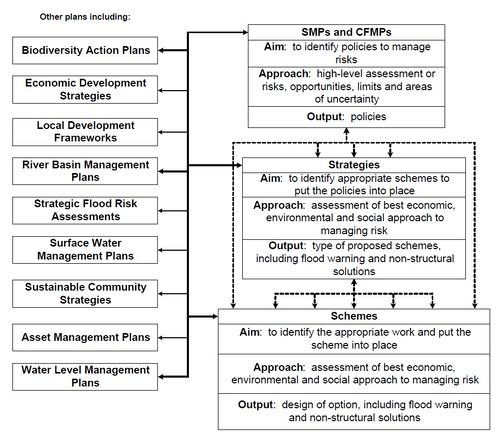

Thus, the SMP itself is intended to define the policy option, but not the precise physical form of the defence option. There will almost certainly be a number of generic solutions that will satisfy the requirements that have been identified in the SMP. There are further stages of study required to reach a final definitive scheme for implementation. Generic solutions will be identified through a Strategy Study for sections of coastline that have been identified as requiring remedial or new works. The final stage concerns a specific scheme for which a scheme specific study will compare alternative options and define the optimum scheme that best satisfies all of the technical, financial and socio-economic criteria that have been agreed. The overall framework is described in Table 2.

| Stage | SMP | Strategy | Scheme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aim | To identify policies to manage risks | To identify appropriate schemes to put the policies into practice | To identify the type of work to put the preferred scheme into practice |

| Delivers | A wide ranging assessment of risks, opportunities, limits and areas of uncertainty | Preferred approach, including economic and environmental decisions | Compare different options for putting the preferred scheme into practice |

| Output | Policies | Type of scheme ( such as a seawall) | Design of works |

| Outcome | Improve management for the coast over the long-term | Management measures that will provide the best approach to managing floods and the coast for a specified area | Reduce risks from floods and coastal erosion to people and assets |

Policy options were further detailed in the 2006 DEFRA [8] guidance providing the following four SMP policies available to shoreline managers:

- Hold the existing defence line by maintainimg or changing the standard of protection. This policy should cover those situations where work or operations are carried out in front of the existing defences (such as beach recharge, rebuilding of the toe of a structure, building offshore breakwaters etc.) to improve or maintain the standard of protection provided by the existing defence line.

- Advance the existing defence line by building new defences on the seaward side of the original defences. This applies only to policy units where significant land reclamation is being considered.

- Managed Realignment by allowing the shoreline to move backwards or forwards, with management to control or limit the movement (such as reducing ersion or building new defences on the landward side of the original defences).

- No active intervention where there is no investment in coastal defences or operations.

The selection of the most appropriate policy option requires a clear focus on the assessment and management of coastal flooding and erosion risks over a one hundred year period beyond the initial appraisal so that there is a strong need for awareness of the longer-term implication of coastal evolution. There is also a clear need for a better appreciation of the uncertainties associated with predicting future shoreline management requirements coupled with a recognition that current defence policies may no longer be feasible or acceptable in the future.

DEFRA has encouraged the development of a strategic framework for flood and coastal erosion risk management based on Shoreline Management Plans (SMPs) and Catchment Flood Management Plans (CFMPs). These are high level plans, which have various relationships with other high level plans, strategies and schemes and other planning initiatives as shown schematically in Figure 2. These plans are based on a risk-based approach, giving more consideration to ‘risk management’ and ‘adaptation’ as opposed to only ‘protection’ and ‘defence’ as well as considering impacts within the whole of a catchment or shoreline process area.

More specific best practice guidance on how to undertake appraisals has been published by the Environment Agency (2010) [10]. This was a collaborative project between the Environment Agency and the Maritime Local Authorities in England and Wales. It is a comprehensive document and justifiably describes itself as a single reference point for information that currently exists on the coast and its aim is to help and guide practitioners in managing the coast. Whilst intended as a technical guide for all operating authorities, it is essential reading for any practitioner involved in managing the coastline in these and any other regions. A useful review of coastal risk management and adaptation as part of sustainable shoreline management in England and Wales is also provided by Pontee and Parsons (2010[11], 2012[12]).

Whilst these frameworks have been largely developed in this form in the UK they are equally applicable, in principle, to any region of the world. The outcome of the final stage focuses on the scheme appraisal process and also defines the type of structure or management strategy that should be adopted.

Legislation and required procedures will vary from country to country, so it is not possible to cover all of the possibilities in this article. However, a common theme of any modern day practice does focus on the need to properly carry out the appropriate planning steps, which include appropriate risk analyses leading to project optimisation. The new Coastal Engineering Manual Part V, Coastal Project Planning and Design [13] provides both a general framework as well as information that relates to procedures in the USA.

Adaptation to climate change

The general principles of modern coastal management, can be applied in any part of the world, although there will always be a regional context, which will mould the application of the general principles. The many issues surrounding predicted climate change have added another layer of complexity to coastal management, which are now being seriously addressed in terms of future management. One key aspect of coastal management includes identifying and quantifying coastal hazards and climate change impacts to assess coastal vulnerability. This can best be achieved by carrying out a comprehensive risk assessment to assess system reliability, using probability methods. Coastal management is then faced, inter alia, with determining policies and practices for adaptation (e.g. hard and soft engineering, managed re-alignment, no active intervention) in response to coastal vulnerability. Many of the recent developments in coastal management have originated in the UK and other European coastal states and in North America. The UK in particular has an extremely varied coastal geomorphology, experiences large variations in waves, tides, water levels and currents, and is relatively densely populated. It is perhaps not surprising therefore, that many developments in coastal management have been initiated in the UK and embedded in central government policies for allocation of resources to coastal defences in the UK. It should, however, be noted that the UK is not routinely subject to nature’s most extreme weather found in hurricanes or exposure to tsunami events, which are so detrimental in other parts of the world.

An example of adaptation to climate change in Barbados (Case Study)

The Coastal Zone Management Unit (CZMU) of Barbados has adopted these approaches to address coastal erosion and flooding caused by past development activity and now potentially climate change and sea level rise, as described in detail by Mycoo and Chadwick (2012) [14]. One pioneering example from Barbados is the combination of hard and soft engineering, green architecture, and landscaping in some coastal locations. Examples of more recently built seawalls in combination with mini-headlands and groynes are those along the beach face at Welches in Christ Church and Rockley Beach. These structures have minimised erosion and increased beach accretion along certain parts of the coast. They have also reduced the vista of a highly engineered shoreline through the integration of aesthetically pleasing boardwalks and landscaping that help the beach look more natural rather than artificial in appearance (see Figure 3). In addition, the seawall and boardwalk have become multifunctional in that they are for not only coastal protection, but provide access to other beaches. Additionally, locals ply their souvenirs or use them for leisurely walks and exercise.

Related articles

- Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM)

- Shore nourishment

- Dune stabilisation

- Shore protection vegetation

- Ecological enhancement of coastal protection structures

- Climate adaptation measures for the coastal zone

- Coastal cities and sea level rise

- Policy instruments for integrated coastal zone management

- Hard coastal protection structures

- Dealing with coastal erosion

- Human causes of coastal erosion

- Natural causes of coastal erosion

Further reading

Publication 2000 - Beach Dunes - a guide to managing coastal erosion in beach dune systems

References

- ↑ Mangor, K., Drønen, N. K., Kaergaard, K.H. and Kristensen, N.E. 2017. Shoreline management guidelines. DHI https://www.dhigroup.com/marine-water/ebook-shoreline-management-guidelines

- ↑ Reeve, D., Chadwick, A. and Fleming, C. 2018. Coastal Engineering: Processes, Theory and Design, Practice 3rd Edition. CRC press, 512 pp.

- ↑ Fleming, C. A. 1989. The Anglian Sea Defence Management Study. In Coastal Management. I.C.E. Thomas Telford, London, UK

- ↑ Townend, I.H. 1990. Frameworks for Shoreline Management, PIANC Bulletin No 71: 72-80

- ↑ Burgess, K. 2002. Futurecoast – the integration of knowledge to assess the future coastal evolution at a national scale. Proceedings 28th Coastal Engineering Conference, ASCE New York

- ↑ Motyka, J.M. and Brampton, A.H. 1993. Coastal management: mapping of littoral cells HR Wallingford, Report SR328

- ↑ Brampton, A., ed. 2002. Coastal defence, London: Thomas Telford

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 DEFRA 2006a. Shoreline management plan guidance Volume 1: Aims and requirements. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69206/pb11726-smpg-vol1-060308.pdf

- ↑ DEFRA 2006b. Shoreline management plan guidance Volume 2: Procedures. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/69207/pb11726v2-smpg-vol2-060523.pdf

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Environmental Agency 2010. Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management appraisal guidance. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/flood-and-coastal-erosion-risk-management-appraisal-guidance

- ↑ Pontee, N.I. and Parsons, A. 2010. A review of coastal risk management in the UK. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Maritime Engineering Journal UK 163: 31-42

- ↑ Pontee, N.I. and Parsons, A. 2012. Adaptation as part of sustainable shoreline management in England and Wales. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Maritime Engineering Journal UK 165: 113-130

- ↑ USACE 2012. Coastal Engineering Manual. USACE, 2012. Coastal engineering manual. Report No 110-2-1100. Washington DC: US Army Corps of Engineers https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/USACE-Publications/Engineer-Manuals/u43544q/636F617374616C20656E67696E656572696E67206D616E75616C/

- ↑ Mycoo, M. and Chadwick, A. 2012. Adaptation to Climate Change: The Coastal Zone of Barbados. Maritime Engineering, UK 165: 159-168