Beach groundwater

Beach morphodynamics not only depends on water flow over the beach surface, but also on subsurface water flow. Surface flow and subsurface flow are related through infiltration and exfiltration. The groundwater table fluctuates at different timescales: the timescale of swash (wave uprush and backwash), the timescale of alternating high and low tidal waters and the seasonal time scale of storm surges and fresh water runoff. The water flow through the beach surface influences the net sediment transport up or down the beach, resulting in accretion or erosion (see Swash zone dynamics). The water circulation associated with the fluctuating groundwater table influences the mixing of seawater and fresh water, with an impact on subsurface seawater intrusion (see Submarine groundwater discharge). This article introduces some principles of beach groundwater dynamics.

Contents

Subsurface zones

In this article we consider beach soils which are homogeneous over a depth range of at least the tidal range and the swash excursion. Three zones in the beach subsurface soil can be distinguished:

- the unsaturated upper beach (also called vadose zone), where the pores (sediment grain interstices) contain air as well as water. The vadose zone extends from the top of the beach surface to the capillary fringe. Water infiltrating in the vadose zone has a pressure head less than atmospheric pressure, and is retained by a combination of adhesion and capillary action.

- the intermediate capillary fringe (tension-saturated zone), in which groundwater seeps up from the water table by capillary action, completely filling the pores. The thickness of the capillary fringe can be up to about one meter in very fine sediment and not exceed a few centimeters in very coarse sediment.

- the saturated lower beach (phreatic zone), the zone below the water table where the pressure head equals the atmospheric pressure and where grain interstices are completely filled with water. The pore space, which is a fraction of the grainsize, largely determines the hydraulic conductivity of the soil. Pore water can contain a small fraction of air which strongly influences the transmission depth of pore water pressure fluctuations (see Wave-induced soil liquefaction).

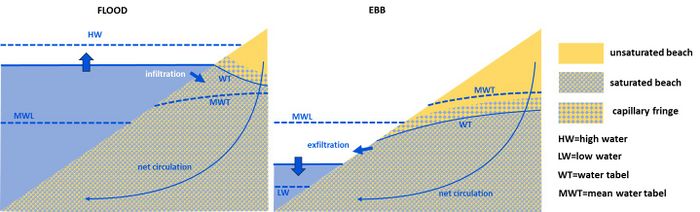

Groundwater response at the tidal time scale

Figure 1 shows the groundwater response of a sloping beach on the tidal time scale. On this time scale, sea level can be considered as rising and falling with a nearly horizontal flat surface. The water table rises faster during high tide (rising sea level) than it falls during low tide (falling sea level). Water infiltrates the dry beach face more easily than it drains from the sand matrix, unless the beach consists of very porous coarse material. The tidal mean water table is therefore higher than the mean sea level[2]. Most seawater infiltrates near the high tide mark and exfiltrates near the low tide mark, resulting in a net groundwater circulation from the upper to the lower tidal zone.

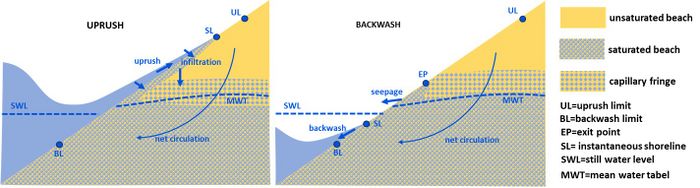

Groundwater response at the wave time scale

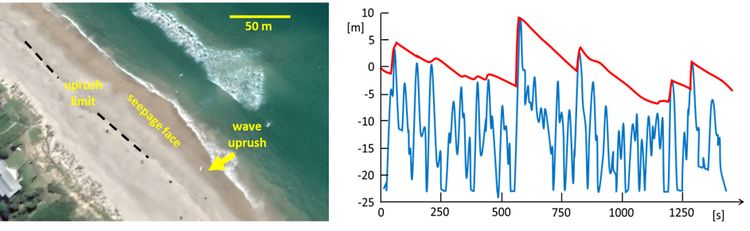

Figure 2 illustrates seawater infiltration into the unsaturated beach. Here, the water table and the capillary fringe are lagging behind the wave uprush, a situation that typically occurs during flood. A wetting front forms beneath the uprushing swash lens, resulting in downward infiltration through the unsaturated zone. During backwash, the water table intersects with the beach surface above the retreating backwash lens, forming a seepage face with a shiny appearance where groundwater exfiltrates (Fig. 3). The exit level (intersection of the water table with the beach surface) gradually declines and finally drops below the capillary fringe.

Similarly as with the tide, seawater infiltrates the beach more readily during the uprush stage than it drains during the backwash stage[3]. The resulting elevation of the water table is further enhanced by wave set-up. There is also a net groundwater circulation from the upper to the lower tidal zone in this case, as seawater infiltration is greatest in the upper swash zone, while most exfiltration occurs near the backwash limit – the point where the next incoming wave collapses onto the beach. Beach sand permeability and water saturation greatly influence the water exchange rate across the beach face. In the case of a coarse sandy beach, the unsaturated zone is rapidly filled by the infiltrating seawater. In fine sediment, on the other hand, the wedge-shaped wetting front is kept close to the beach surface for most of the uprush and does not penetrate far into the saturated zone[1]. The wetting front declines during backwash, but this decline is much slower than the backwash retreat (Fig. 4).

Related articles

- Swash

- Swash zone dynamics

- Submarine groundwater discharge

- Groundwater management in low-lying coastal zones

- Beach drainage

- Wave-induced soil liquefaction

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Zheng, Y., Yang, M. and Liu, H. 2024. Coastal groundwater dynamics with a focus on wave effects. Earth-Science Reviews 256, 104869

- ↑ Turner, I.L., Coates, B.P. and Acworth, R.I. 1997. Tides, waves and the super-elevation of groundwater at the coast. J. Coast. Res. 13: 46–60

- ↑ Heiss, J.W., Ullman, W.J. and Michael, H.A. 2014. Swash zone moisture dynamics and unsaturated infiltration in two sandy beach aquifers. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 143: 20–31

- ↑ Cartwright, N., Baldock, T.E., Nielsen, P., Jeng, D-S. and Tao, L. 2006. Swash-aquifer interaction in the vicinity of the water table exit point on a sandy beach. J. Geophys. Res. 111, C09035

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|