Beach drainage

Definition of Beach drainage system:

A beach dewatering system or beach drain, is a shore protection system working on the basis of a drain in the beach. The drain runs parallel to the shoreline in the wave up-rush zone. The beach drain increases the level of the beach near the installation line, thus also increasing the width of the beach.

This is the common definition for Beach drainage system, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

This article describes the working and application of a beach drainage system. Beach drainage is an example of a soft shoreline protection solution.

Contents

Natural shoreline mechanisms

Uprush and backwash

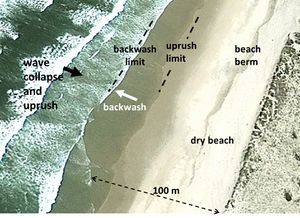

The transport of sediment across the beach face is performed by wave uprush and backwash. The uprush moves sand onshore while the backwash transports it offshore, see Swash zone dynamics.

The wave motion also interacts with the beach groundwater flow. Seawater may infiltrate into the sand at the upper part of the beach (around the shoreline) during swash wave motion if the beach groundwater table is relatively low. In contrast, groundwater exfiltration may occur across the beach with a high water table, see Appendix Beach groundwater dynamics. Such interactions have a considerable impact on the sediment transport in the swash zone.

Relevant mechanisms

Three mechanisms related to the uprush and backwash processes (see definitions of coastal terms) are relevant with respect to beach drainage. These mechanisms directly affect the resulting sediment transport. Given a certain groundwater table in the beach profile and consider a situation without active beach drainage:

- during uprush: sediment stabilisation and boundary layer thinning due to infiltration of water; the mass of water which has to return to sea diminishes; sediment particles are transported in landward direction,

- during backwash

- less water retuns to sea; however, still rather high velocities due to gravity effects; sediment particles are transported in seaward direction,

- destabilisation and boundary layer thickening due to exfiltration of groundwater.

Under accretive (wave) conditions the landward directed sediment transport processes apparently over-class the seaward directed processes. Under erosive (wave) conditions it is the other way around.

Working and application of beach drainage

Active beach drainage

When an active drainage system is installed under the beach face and parallel to the coastline, the aforementioned mechanisms will alter:

- during uprush: seawater infiltration under an artificially lowered water table was found to enhance, but transport of particles in landward direction hardly change,

- during backwash:

- less water returns to sea (smaller transport of particles in seaward direction),

- groundwater ex filtration is reduced.

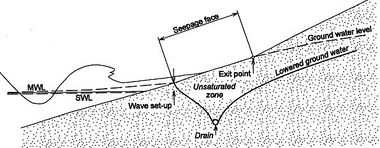

Consequently it is expected that an artificially lowering of the groundwater table, with a drainage system, changes the coastal processes. In case of accretive conditions an increase of the accretion is expected. In case of erosive conditions a decrease of the beach erosion results. The above conclusion is confirmed by field and laboratory measurements. Figure 2 illustrates the lowering of the groundwater level due active beach drainage.

Method

The drain consists of a permeable plastic pipe installed 1.0 to 2.0 m below the beach surface in the wave up-rush zone parallel to the coastline. If there is a significant tide, the drain must be installed close to the MHWS line, i.e. near the shoreline. The only visible part of the drain installation is the pumping well and a small control house. The pipes of a beach drainage system drain the seawater away to a collector sump and pumping station. The collected seawater may be discharged back to sea but can also be used to various applications (marinas oxygenation, desalination plants, swimming pools…).

Functional characteristics

The conditions influencing the function of the drain are summarised in the following:

- The site must have a sandy beach. The beach sediments must be sand, preferably with a mean grain diameter in the range of 0.1 mm < d50 < 1.0 mm and preferably sorted to well sorted (Cu = d60/d10 < 3.5). These conditions give the permeability that provides optimal functionality of the beach drain.

- The beach drain works by locally lowering the groundwater table in the uprush zone, which decreases the strength of the down-rush as a higher fraction of the water percolates into the beach. Furthermore, the physical strength properties of the beach sand is increased remarkably by the lowering of the water table in the wave up-rush zone thereby making the beach more resistant against erosion. The groundwater table in the beach is a function of several factors, the most important of which are: a) the groundwater table conditions in the coast and the hinterland, b) the groundwater table caused by tide and storm surge, and c) the groundwater table caused by waves.

- A high groundwater table in the coast and the hinterland influences beach stability and beach formation. The hinterland-based groundwater table saturates a large portion of the beach, causing groundwater seepage through the foreshore. This seepage tends to destabilise (fluidise) the foreshore. The beach drain locally lowers the groundwater table to the level of the drain and counteracts the destabilisation.

- The beach drain works well at locations with relatively high tide because the tide generates an elevated groundwater table in the beach, which can be lowered considerably by the drain. It can therefore be stated that the presence of high tide at a location enhances the functionality of the drain.

- The presence of high storm surges will affect the functionality of the drain by moving the uprush zone landwards away from the drain. The function of the drain during high surge conditions will mainly be indirect; the previously accumulated sand will act as a buffer for the erosion during the storm. When the storm surge falls, the elevated groundwater-level in the beach will increase beach erosion if there is no beach drain to prevent it.

- Waves on a beach increase the height of the local groundwater table in the beach, partly due to the wave run-up on the foreshore and partly due to the locally elevated water-level in the uprush zone called wave set-up. Once again, the beach drain counteracts this.

- The beach drain requires some wave activity on the beach as the drain works by manipulating the downrush conditions on the foreshore. Too small and too high waves make the beach drain inefficient. It works best on moderately exposed coasts.

- As the beach drain system functions only on the foreshore in the uprush zone, it does not directly protect the entire active profile against erosion. Consequently, it is best suited at locations with seasonal beach fluctuations or where the objective is a wider beach at an otherwise stable section of the shoreline. For locations that experience on-going recession of the entire active coastal profile, the beach drain is probably only suitable combined with other measures. The long-term capability of the beach drain under such circumstances remains to be tested.

Applicability

The beach drain is best suited for the management of beaches with the following characteristics:

- Sandy beaches

- Moderately exposed to waves

- Exposed to tide

- Suffering from high groundwater table on the coast and on the beach

- Exposed to seasonal fluctuations of the shoreline

- Exposed to minor long-term beach erosion

- Locations with a narrow beach, where a wider beach is desired

The beach drain is, however, not recommended as a primary shore or coastal protection at locations with the following characteristics:

- Severely exposed locations

- Protected locations

- Locations exposed to severe long-term shore erosion and coast erosion

The system includes minimal environmental impact compared with various hard protection methods.

Practical experience with beach drainage

Several tests of beach drainage have been performed in wave flumes. More than 30 beach drainage systems have been installed in Denmark, USA, UK, Japan, Spain, Sweden, France, Italy and Malaysia. The beach drain method is patented worldwide by GEO, Denmark. Most of the laboratory tests were positive, showing beach stabilization and accretion. However, the evidence of field applications is more controversial[1]. Beach stabilization and accretion occurred in a number of cases, but in several other cases no significant positive effect was observed. Due to these mixed results, beach drainage has not been widely implemented since its introduction in the 1980ies. Convincing evidence from long-term real-scale applications and clear guidelines for the successful implementation of beach drainage systems are still lacking[1].

Related articles

- Dealing with coastal erosion

- Shoreline retreat and recovery

- Swash zone dynamics

- Shore nourishment

- Gravel Beaches

Appendix Beach groundwater dynamics

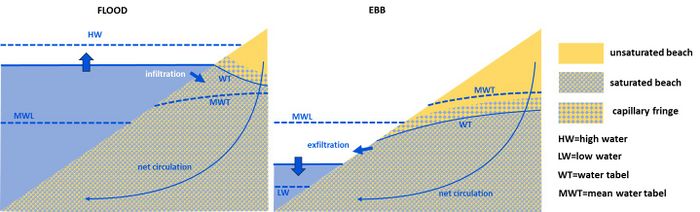

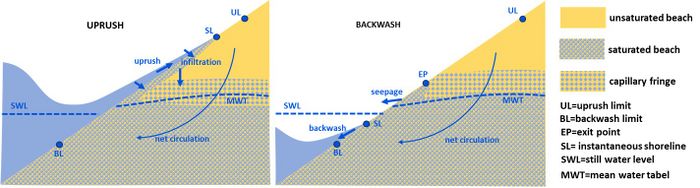

The groundwater table of sandy beaches varies in response to sea level variations at tidal and wave time scales. This variation is illustrated in the figures A1 and A3 for situations where the mean groundwater level of the backshore is not much higher than the mean sea level. Three distinct beach zones are: (1) the unsaturated upper beach (also called vadose zone), (2) the saturated lower beach (phreatic zone) and (3) the intermediate capillary fringe (tension-saturated zone). The water table is the surface where the pressure head equals the atmospheric pressure.

Figure A1 shows the groundwater response of a sloping beach on the tidal time scale. On this time scale, sea level can be considered as rising and falling with a nearly horizontal flat surface. The water table rises faster during high tide (rising sea level) than it falls during low tide (falling sea level). Water infiltrates the dry beach face more easily than it drains from the sand matrix, unless the beach consists of very porous coarse material[3]. The tidal mean water table is therefore higher than the mean sea level. Most seawater infiltrates near the high tide mark and exfiltrates near the low tide mark, resulting in a net groundwater circulation from the upper to the lower tidal zone.

Fig. A3 illustrates seawater infiltration into the unsaturated beach. Here, the water table and the capillary fringe are assumed to lag behind the wave uprush, a situation that typically occurs during flood. A wetting front forms beneath the uprushing swash lens, resulting in downward infiltration through the unsaturated zone. During backwash, the water table intersects with the beach surface above the retreating backwash lens, forming a seepage face with a shiny appearance where groundwater exfiltrates (Fig. A2). This seepage face gradually declines and finally drops below the capillary truncated zone.

Similarly as for the tide, seawater infiltrates the beach during the uprush stage more easily than it drains during the backwash stage[4]. The resulting elevation of the water table is further enhanced by wave set-up. There is also a net groundwater circulation from the upper to the lower tidal zone in this case, as seawater infiltration is greatest in the upper swash zone, while most exfiltration occurs near the backwash limit – the point where the next incoming wave collapses onto the beach. Beach sand permeability and water saturation greatly influence the water exchange rate across the beach face. In the case of a coarse sandy beach, the unsaturated zone is rapidly filled by the infiltrating seawater. In fine sediment, on the other hand, the wedge-shaped wetting front is kept close to the beach surface for most of the uprush and does not penetrate far into the saturated zone[2].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Fischione, P., Pasquali, D., Celli, D., Di Nucci, C. and Di Risio, M. 2022. Beach Drainage System: A Comprehensive Review of a Controversial Soft-Engineering Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 145

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Zheng, Y., Yang, M. and Liu, H. 2024. Coastal groundwater dynamics with a focus on wave effects. Earth-Science Reviews 256, 104869

- ↑ Turner, I.L., Coates, B.P. and Acworth, R.I. 1997. Tides, waves and the super-elevation of groundwater at the coast. J. Coast. Res. 13: 46–60

- ↑ Heiss, J.W., Ullman, W.J. and Michael, H.A. 2014. Swash zone moisture dynamics and unsaturated infiltration in two sandy beach aquifers. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 143: 20–31

Other literature sources

- Danish Geotechnical Institute (DGI) 1992. Beach Management System – Documentation, Job No. 300001414. Lyngby, Denmark (20 p.)

- Mangor, K., Drønen, N. K., Kaergaard, K.H. and Kristensen, N.E. 2017. Shoreline management guidelines. DHI https://www.dhigroup.com/marine-water/ebook-shoreline-management-guidelines

- Karambas Th. V. (2003). Modelling of infiltration – exfiltration effects of cross-shore sediment transport in the swash zone, Coastal Engineering Journal, 45, no 1: 63-82.

- Law A. W-K., Lim S-Y, Liu B-Y (2002). A note on transient beach evolution with artificial seepage in the swash zone, Journal of Coastal Research, 18 (2): 379-387.

- Sato M., Fukushima T., Nishi R. Fukunaga M. (1996), On the change of velocity field in nearshore zone due to coastal drain and the consequent beach transformation, Proc. 25th International Conference on Coastal Engineering 1996, ASCE, pp. 2666-2676.

- Sato M., Nishi R., Nakamura K., Sasaki T., (2003). Short-term field experiments on beach transformation under the operation of a coastal drain system, Soft Shore Protection, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp 171-182.

- Ioannidis D. and Th. V. Karambas (2007): "‘Soft’ shore protection methods: Beach drain system", 10th Int. Conf. on Environmental Science and Technology, CEST2007, Kos Island, GREECE, A-528-535

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|