Siltation in harbors and fairways

Contents

Introduction

This article addresses the siltation in semi-enclosed harbor basins and fairways in open water with sediments from the surrounding waters. In its most basic form, siltation occurs when the sediment transport capacity is locally exceeded by the supply of sediment.

Siltation in semi-enclosed harbor basins

For harbor basins, siltation with fine (cohesive) sediments is in general more problematic than siltation with coarser sediments (sand), as the siltation rates with fines are often larger, and at times, these sediments are contaminated as well. Thus we focus on siltation with fine sediments, which are generally carried by the flow in suspension (see Dynamics of mud transport).

The harbor basin and the ambient water system exchange sediment-laden water by the three mechanisms described below. Because the basin is semi-enclosed, no net inflow or outflow of water occurs (over a long-enough period). However, there is a gross exchange of water – sediment-rich water from the ambient system is exchanged with sediment-poor water from the basin itself. In zero-order approach we assume that the sediment flux may be treated as the product of water flux and SPM (suspended particulate matter) concentration, corrected for a trapping efficiency (the fraction of sediment that enters the harbor and deposits).

A harbor basin can be situated along a river, a lake, a tidal river, a coast, an estuary etc. We always assume that the water body in front of the harbor entrance flows with a characteristic velocity [math]U[/math]. In a tidal river and along a coast, tides play a major role, whereas in estuaries, and along some coasts, density currents are also important.

The three relevant mechanisms exchanging sediment-laden water between the ambient water body and the harbor basin are (see also Fig. 1):

- Horizontal exchange: large scale circulations in the harbor’s mouth driven by flow separation, entrainment and stagnation effects at the downstream side of the basin’s entrance. This mechanism always plays a role in flowing ambient water. Net inflow/outflow of water is always zero.

- Tidal filling: during rising tide, sediment-laden water flows into the basin, while during falling water, the same amount of water flows out of the basin, containing less sediment, though. Over a tidal period, no net amount of water is exchanged. This mechanism plays a role in tidal rivers and along open coasts.

- Density currents: gradients in salinity induce density currents with a near-bed current (which contains the majority of the sediment) against the direction of that gradient. Salinity-induced density currents play a role in estuaries and coastal systems with salinity gradients. Eysink (1989[3]) emphasized the importance of this mechanism. Density currents can also be induced by gradients in SPM and temperature.

Note that these mechanisms interact. For instance, during tidal filling, the wake induced by flow separation in the harbor’s mouth is deflected into the basin, and horizontal exchange thus becomes less effective in exchanging water between the basin and the surrounding water body.

These three mechanisms are illustrated below for an estuary, where salinity variations are more or less in phase with ebbing and flooding of the tide. In general, water level and tidal velocity are out of phase, and in the following we assume a phase difference of [math]45^{\circ}[/math]. During flood, flow separation occurs at the down-estuary side of the harbor basin, and the wake is deflected into the basin during rising tide, and out of the basin during falling tide. Thus, relatively, little water is exchanged during falling water and ebb, which is therefore neglected in this zero-order estimation. Tidal filling is in phase with rising and falling water. The salinity in the estuary in front of the harbor basin is more or less in phase with flood and ebb – for a harbor basin situated down-estuary (close to the sea) salinity in the estuary is larger than in the basin during flood, while the opposite is true during ebb. Hence, a near-bed sediment-rich density current flows into the basin during flood, while, owing to siltation in the basin, a near-bed sediment-poor density current flows out of the basin during ebb. This phasing is sketched in Fig. 2, showing that sediment import into a harbor basin is unevenly distributed over a tidal period.

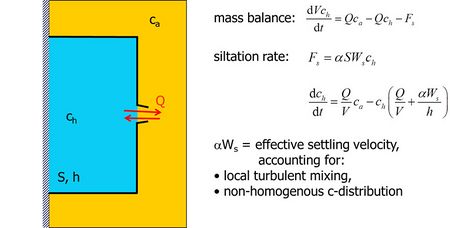

Eysink[3] was the first to quantify the siltation rate in harbor basins, using a zero-order assessment (see also [4][5]). The basis for this assessment is the zero-order sediment balance, sketched in Fig. 3, where it is assumed that the SPM-values in the harbor basin [math]c_e[/math] (and thus the siltation rate) are proportional to the ambient SPM-value [math]c_a[/math]. The equilibrium solution to this simple differential equation is given in equation (1):

[math]c_e=\large\large\frac{\lt Q\gt }{\lt Q\gt +\alpha S W_s}\normalsize c_a , \qquad (1) [/math]

in which [math]S[/math] = projected basin’s surface. The exchange flow [math]Q[/math] is determined by the three processes described above:

[math]\large\large\frac{1}{T}\normalsize \int_0^T Q dt \equiv \lt Q\gt =\lt Q_t\gt +\lt Q_e\gt +\lt Q_d\gt , \qquad(2) [/math]

where [math]\lt Q_t\gt [/math] is the gross water exchange by tidal filling (angular brackets implies averaging over tidal period), [math]\lt Q_e\gt [/math] is the gross water exchange by horizontal circulation (entrainment), and [math]\lt Q_d\gt [/math] is the gross water exchange by density currents.

Eysink[3] proposed a number of coefficients to quantify these gross water exchange rates:

[math]\lt Q_t\gt =\large\frac{V_t}{T}\normalsize, \quad \lt Q_e\gt =f_e A U - f_{e,t}\lt Q_t\gt , \quad \lt Q_d\gt =f_d A \sqrt{ \large\frac{\Delta \rho_s g h_0}{\rho}\normalsize } - f_{d,t} \lt Q_t\gt , \qquad(3)[/math]

where [math]V_t[/math]= tidal volume of harbor basin, [math]T[/math]= tidal period, [math]A[/math]= cross section harbor entrance, [math]U[/math]= characteristic velocity along the harbor entrance, [math]\Delta \rho_s[/math] = characteristic salinity-induced density difference across the harbor entrance, [math]h_0[/math] is local water depth, the coefficients [math]f_{e,t}, f_{d,t}[/math] reflect a reduction in exchange efficiency during rising tide, [math]\alpha=1-u_h^2/u_{cr}^2[/math], [math]u_h[/math] is a characteristic velocity in the harbor basin, and [math]u_{cr}[/math] is a threshold velocity below which sediment can permanently settle of the basin’s bed.

The following empirical coefficients (Fig. 4) were proposed by Eysink[3], showing also the dependence of [math]f_e[/math] on the harbor entrance orientation with respect to the flood direction.

Next to these three exchange mechanisms, also shipping itself can induce sediment import into harbor basins, in particular in lakes and canals, where the above-mentioned mechanisms are small. Fig. 5 sketches this process, for which however no general quantification exists.

Siltation in fairways

Siltation in fairways in open water can occur with fine (silt) and coarse (sand) sediment, which may be transported as suspended load and/or as bed load. Fairways in rivers and estuaries (“open water”) behave differently. In the latter case full morphodynamic analyses are required for assessing these siltation rates, as the navigation channel and ambient water system can interact strongly. This is for instance the case in the Western Scheldt where fairway deepening influences the morphodynamic development of this estuary[6] .

Fig. 6 depicts the refraction of a current, oblique to a navigation channel, over that channel. To understand this picture, the scales of the system have to be considered. A cross-current experiences a sudden increase in water depth (the width of the channel is small compared to the system’s dimensions), thus the flow decelerates locally, as the water flux does not change. However, along the channel, the channel dimensions are much larger than the channel width. Given a constant pressure gradient along the channel, the larger depth within the channel reduces the effective hydraulic drag accelerating the current. Thus, depending on the angle of incidence, the flow accelerates of decelerates. A semi-quantitative analysis is presented below.

The flow velocity in the channel as a function of relative channel depth and angle of incidence (with [math]C[/math]=Chézy coefficient, [math]h[/math]=depth) can be derived from simple geometric arguments:

[math]\large\frac{U_{y,1}}{U_{y,0}}\normalsize =\large\frac{h_0}{h_1}\normalsize ,\quad \large\frac{U_{x,1}}{U_{x,0}}\normalsize =\large\frac{C_1}{ C_0} \left(\frac{h_1}{h_0} \right)^{1/2}\normalsize , \qquad(4)[/math]

where [math]C \approx C_1 \approx C_2[/math] and

[math]U_1=U_0 \large\frac{h_0}{h_1}\normalsize [ \sin^2 \alpha_0 + \large \left (\frac{h_1}{h_0} \right )^3\normalsize \cos^2 \alpha_0 ]^{1/2} , \quad \tan \alpha_1=\large \left (\frac{h_0}{h_1} \right )^{3/2}\normalsize \tan \alpha_0. [/math]

The subscripts [math]x, y[/math] indicate the along-channel and cross-channel projections of the velocity, respectively.

The ratio between the flow velocities inside and outside the navigation channel are plotted in Fig. 7 as a function of the angle of incidence of the ambient flow. Note that up to quite large angles, the flow velocity within the channel is larger than outside the channel. A larger flow velocity implies a larger transport capacity. The implications for channel self-cleansing are discussed below.

A larger flow velocity through a larger cross section implies a larger specific discharge, and the extra water has to come from the channel’s surrounding waters. However, this extra water carries also extra sediment. For simplicity, only along-channel flow is discussed, as illustrated in Fig. 8. Continuity and substitution from equation (4) yields a relation for an “effective channel width” [math]b_0[/math] representing the area from which the “extra” water and sediment is attracted,

[math]\large\frac{b_0}{b_1}\normalsize =\large\frac{U_1 h_1}{U_0 h_0}\normalsize =\large\frac{C_1}{C_0} \left (\frac{h_1}{h_0} \right )^{3/2} \normalsize. \qquad(5)[/math]

Ignoring settling and erosion time lag effects, the equilibrium transport [math]T_e[/math] is represented by a power of the local flow velocity: [math]T_e \propto u_*^n[/math], where [math]u_*[/math] = shear velocity and in which [math]n[/math] = 3 represents bed load and [math]n[/math] = 4 – 6 represents suspended load (see e.g. Sediment transport formulas for the coastal environment). Substitution from equations (4) and (5) yields a relation for the sediment transport capacity inside the channel in relation to the sediment transport capacity outside the channel:

[math]\large\frac{T_{e,1}}{T_{e,0}}\normalsize =\large\frac{b_1}{b_0} \left (\frac{u_{*,1}}{u_{*,0}} \right )^n\normalsize =\large\frac{b_1}{b_0} \left (\frac{U_1 C_0}{U_0 C_1} \right )^n\normalsize =\large\frac{b_1}{b_0} \left (\frac{h_1}{h_0} \right )^{n/2}\normalsize = \large\frac{C_0}{C_1} \left (\frac{h_1}{h_0} \right )^{(n-3)/2} \normalsize. \qquad(6)[/math]

As [math]C_1[/math] is (slightly) larger than [math]C_0[/math], the sediment transport capacity within the channel is smaller than outside in case of bed load ([math]n[/math] = 3). Thus the channel will silt up. However, for suspended load, equation (6), when [math]n[/math] = 4 – 6, equation (6) predicts that the fairway is self-cleansing, and possibly even eroding. Advanced three-dimensional numerical sediment transport models yield a similar prediction, at least qualitatively. This result conflicts with observed fairway sedimentation, however.

This paradox illustrates that some important phenomena are missing in the above analysis. This holds in particular for the omission of wave effects. Waves stir up and can transport large amounts of sediments in the shallows surrounding the fairway, whereas wave activity on the channel’s bed is small. Linear wave theory gives a first-order estimate of the ratio of maximum wave-induced bed shear stresses:

[math]\large\frac{\hat \tau_{b,c}}{\hat \tau_{b,\infty}}\normalsize = \large \left (\frac{u_{b,c}}{u_{b,\infty}} \right )^2\normalsize =\large \left (\frac{\sinh kh_{\infty}}{\sinh kh_c} \right )^2 \normalsize \approx \large \left (\frac{h_{\infty}}{h_c} \right )^2 \normalsize , \qquad(7) [/math]

where the subscript [math]b[/math] indicates the near-bed value. The most right member follows from the inequality [math]k=2 \pi / \lambda \lt \lt 1 /h[/math] (wavelength [math]\lambda \gt \gt h [/math]).

This ratio is plotted in Fig. 9, showing that bed shear stresses on the channel bed decrease rapidly with channel depth. Moreover, wave-induced shear stresses are often larger than flow-(tide) induced stresses. Hence, ignoring effects of waves on the siltation rates in navigation channels may give an entirely wrong picture of channel’s maintenance needs.

Other effects, amongst which estuarine circulation, may also affect channel siltation. However, these are not accounted for in the present zero-order assessment

This analysis yields two important observations:

- Channel siltation may vary strongly over the year, in particular if the local climate is characterized by seasonal variations in wave conditions,

- Channel orientation may strongly influence siltation rates, thus maintenance costs.

Literature provides some simple engineering rules for assessing channel siltation [math]F_c[/math] with channel width B:

- Mayor-Mortensen-Fredsøe[9]:

[math]F_c = \large\frac{T_0}{\cos(\alpha_0-\alpha_1)} \normalsize \left [ 1 - \exp \large \left ( - \frac{A_m h_0 B}{h_1 \sin \alpha_1 \cos(\alpha_0-\alpha_1)} \right) \normalsize \right ] -T_1 \left [ 1- \exp \large \left (-\frac{A_m B}{\sin \alpha_1} \right ) \normalsize \right ] \sin \alpha_1 , \qquad(8) [/math]

with [math]A_m=W_s^2/ \epsilon_1 U_1 , \quad \epsilon_1=0.085 h_1 u_{*,1} [/math].

- Bijker[10] :

[math]F_c = \left (\large \frac{T_0}{\cos(\alpha_0-\alpha_1)} \normalsize -T_1\right ) \left[ 1- \exp \large \left (-\frac{A_b B}{\sin \alpha_1} \right ) \normalsize \right ] \sin \alpha_1 , \qquad(9) [/math]

with [math]A_b=\large\frac{F_B W_s}{h_1 U_1}\normalsize, \quad F_B=\large\frac{a_1}{a_2-a_3}\normalsize [/math] and

[math]a_1=\large\frac{u_{*,1}}{u_{*,0}-u_{*,1}}\normalsize, \quad a_2=\large\frac{W_s}{0.085 u_{*,1}}\normalsize \left [1- \exp \large \left (-\frac{W_s}{0.085 u_{*,0}} \right ) \normalsize \right ], \quad a_3=\large \left (\frac{u_{*,1}}{u_{*,0}} \right )^3 \frac{W_s}{0.085 u_{*,0}}\normalsize \left [ 1- \exp \large \left (-\frac{W_s}{0.085 u_{*,1}} \right ) \normalsize \right ][/math].

- Eysink & Vermaas[11]:

[math]F_c = \left ( \large\frac{T_0}{\cos(\alpha_0-\alpha_1)} \normalsize - T_1 \right ) \left [ 1- \exp \large \left ( - \frac{A_{ev} B}{h_1 \sin \alpha_1} \right ) \normalsize \right ] \sin \alpha_1 , \qquad(9) [/math]

with [math]A_{ev} = 0.03 \large\frac{W_s}{u_{*,1}}\normalsize \left ( 1+\large\frac{2W_s}{u_{*,1}}\normalsize \right ) \left [ 1+4.1 \large \left (\frac{k_s}{h_1} \right )^{0.25}\normalsize \right ][/math].

Note that from our analysis above, the shear velocity has to be corrected for the effects of waves, otherwise misleading results will be obtained.

- The fourth model is by Allersma, known as the “volume-of-cut” method, but which has never been published:

[math]h_{T*}=h_0-(h_0-h_e) \left [ 1- \exp \large \left (-\frac{v T_*}{h_0} \right ) \normalsize \right ][/math].

This simple model is particularly useful in case of deepening an existing channel – data on previous dredging volumes can be used for calibration of the parameter [math]v[/math]. [math]T_*[/math] is an arbitrary time scale (one year, five years, ..), [math]h_0[/math] the initial channel depth, and [math]h_e[/math] the channel’s equilibrium depth (which may be the local water depth in open water).

List of symbols

| parameter | definition | unit |

|---|---|---|

| [math]A[/math] | cross-section harbor mouth | [math]m^2[/math] |

| [math]A_b, A_{ev}, A_m[/math] | empirical coefficients | |

| [math]b[/math] | channel width | [math]m[/math] |

| [math]C[/math] | Chezy coefficient | [math]m^{1/2}/s[/math] |

| [math]c_a[/math] | ambient suspended particulate matter (SPM) concentration | [math]kg/m^3[/math] |

| [math]c_e[/math] | equilibrium concentration in harbor | [math]kg/m^3[/math] |

| [math]c_h[/math] | SPM concentration in harbor | [math]kg/m^3[/math] |

| [math]F_s[/math] | siltation rate in harbor | [math]kg/s[/math] |

| [math]F_h[/math] | siltation rate in channel | [math]kg/s[/math] |

| [math]F_B[/math] | empirical coefficient | |

| [math]f_d, f_e, f_{d,t}, f_{e,t}[/math] | empirical coefficients | |

| [math]h[/math] | depth | [math]m[/math] |

| [math]k_s[/math] | Nikuradse roughness height | [math]m[/math] |

| [math]n[/math] | power in transport formula | |

| [math]Q[/math] | exchange flow rate | [math]m^3/s[/math] |

| [math]Q_d, Q_e, Q_t[/math] | same; density-, entrainment-, tide-induced | [math]m^3/s[/math] |

| [math]S[/math] | harbor projected surface | [math]m^2[/math] |

| [math]T[/math] | tidal period | [math]s[/math] |

| [math]T_*[/math] | characteristic time scale | [math]s[/math] |

| [math]T_e[/math] | equilibrium sediment transport | [math]kg/m[/math] |

| [math]T_0 (T_1)[/math] | sediment transport outside (inside) channel | [math]kg/m[/math] |

| [math]U[/math] | characteristic velocity | [math]m/s[/math] |

| [math]u_*[/math] | shear velocity | [math]m/s[/math] |

| [math]u_{cr}[/math] | critical velocity | [math]m/s[/math] |

| [math]u_h[/math] | characteristic velocity in harbor basin | [math]m/s[/math] |

| [math]V[/math] | harbor volume | [math]m^3[/math] |

| [math]W_s[/math] | settling velocity | [math]m/s[/math] |

| [math]x[/math] | coordinate along channel | [math]m[/math] |

| [math]y[/math] | coordinate perpendicular to channel | [math]m[/math] |

| [math]\alpha[/math] | efficiency parameter for harbor siltation | |

| [math]\alpha_0[/math] | flow angle ambient current | |

| [math]\alpha_1[/math] | flow angle within channel | |

| [math]\Delta \rho_s[/math] | salinity-induced density difference | [math]kg/m^3[/math] |

| [math]\epsilon_1[/math] | empirical coefficient | |

| [math]v[/math] | empirical coefficient | [math]m/s[/math] |

Related articles

Sediment deposition and erosion processes

Sediment transport formulas for the coastal environment

Manual Sediment Transport Measurements in Rivers, Estuaries and Coastal Seas

Further reading

PIANC, 2008. Minimising harbour siltation, Pianc. Brussels, Belgium.

http://www.leovanrijn-sediment.com/papers/Harboursiltation2012.pdf

References

- ↑ Vanlede, J. and A. Dujardin, 2014. A geometric method to study water and sediment exchange in tidal harbors. Ocean Dynamics 64:1631–1641 DOI 10.1007/s10236-014-0767-9

- ↑ De Boer, W.P. and J.C. Winterwerp, 2016. The role of fresh water discharge on siltation rates in harbor basins. Proceedings, PIANC-COPEDEC IX, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Eysink, W.D. 1989. Sedimentation in harbour basins. Small density differences may cause serious effects. In: 9th International Harbour Congress, Antwerp, Belgium

- ↑ Van Rijn, L.C., 2005. Principles of sedimentation and erosion engineering in rivers, estuaries and coastal seas. Aqua Publications, The Netherlands

- ↑ Winterwerp, J.C. and W.G.M. van Kesteren, 2004. Introduction to the physics of cohesive sediments in the marine environment, Elsevier, Developments in Sedimentology, 56

- ↑ Jeuken, M.C.J.L. and Z.B. Wang. Impact of dredging and dumping on the stability of ebb–flood channel systems. Coastal Engineering 57, 553–566

- ↑ Jensen, J.H., Madsen, E.Ø. and Fredsøe, J., 1999, “Oblique flow over dredged channels – I: Flow description”, ASCE, Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, Vol 125, No 11, pp 1181-1189

- ↑ Jensen, J.H., Madsen, E.Ø. and Fredsøe, J., 1999, “Oblique flow over dredged channels – II: Sediment transport and morphology”, ASCE, Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, Vol 125, No 11, pp 1190-1198

- ↑ Mayor-Mora, R., P. Mortensen and J. Fredsoe, 1976. Sedimentation studies on the Niger River Delta. 15th ICCE, Honolulu, Hawaii

- ↑ Bijker, E., 1980. Sedimentation in channels and trenches. 17th ICCE, Sydney, Australia

- ↑ Eysink, W. and H. Vermaas, 1983. Computational method to estimate the sedimentation in dredged channels and harbor basins in estuarine environments. Int. Conf. on Coastal and Ports Engineering in Developing Countries, Colombo, Sri Lanka; also: Delft Hydraulics, Publication No 307

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|