Difference between revisions of "Chenier"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ Definition| title = Chenier | {{ Definition| title = Chenier | ||

| − | | definition = An accretionary feature consisting of a long, low lying, narrow strip of (gravelly) sand, typically up to | + | | definition = An accretionary feature consisting of a long, low lying, narrow strip of (gravelly) sand, typically up to 4 m high and 40 to 400 m wide, often shelly, deposited in the form of wave-built beach ridge on a swampy, deltaic, or alluvial coastal plain of fine sediment.}} |

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==Chenier plain== | ==Chenier plain== | ||

| − | [[File:ChenierPlainGuinee.jpg|thumb| | + | [[File:ChenierPlainGuinee.jpg|thumb|500px|right|Fig. 1. Chenier plain in Guinée (West Africa). Image Google Earth.]] |

| − | A chenier plain is a strand plain consisting of long, narrow beach ridges (cheniers) and intervening mudflats with marsh or swamp vegetation. The word chenier is derived from the Cajun French word, chène, meaning oak, the dominant tree growing on the crests of cheniers in southwestern Louisiana. Often, relict cheniers can be observed as a series of coast-parallel ridges in the landscape, separated by muddy soil and/or peat<ref>Russell, R.J. and Howe, H.V. 1935. Cheniers of southwestern Louisiana. Geogr. Rev. 25: 449-461</ref>. They are easily distinguishable because of their higher elevation and different composition, generating a striking contrast to their surroundings. Consequently, they are often used for roads, dikes and settlements. Cheniers | + | A chenier plain is a [[strand plain]] consisting of long, narrow beach ridges (cheniers) and intervening mudflats with marsh or swamp vegetation. The word chenier is derived from the Cajun French word, chène, meaning oak, the dominant tree growing on the crests of cheniers in southwestern Louisiana. Often, relict cheniers can be observed as a series of coast-parallel ridges in the landscape, separated by muddy soil and/or peat<ref>Russell, R.J. and Howe, H.V. 1935. Cheniers of southwestern Louisiana. Geogr. Rev. 25: 449-461</ref>. They are easily distinguishable because of their higher elevation and different composition, generating a striking contrast to their surroundings. Consequently, they are often used for roads, dikes and settlements. |

| + | |||

| + | Cheniers serve as a natural barrier that protects the shoreline from wave erosion. Coastal areas protected by cheniers provide better growth conditions for mangroves than areas without such protection<ref>van Bijsterveldt, C.E.J., van der Wal, D., Mancheno, A.G., Fivash, G.S., Helmi, M. and Bouma, T.J. 2023. Can cheniers protect mangroves along eroding coastlines? – The effect of contrasting foreshore types on mangrove stability. Ecological Engineering 187, 106863</ref>. Cheniers promote the formation of a mud bed on the landward side that also absorbs wave energy. Cheniers, mangroves and mud deposits together play an important role in stabilizing the shoreline.<br clear=all> | ||

Latest revision as of 12:20, 13 January 2024

Definition of Chenier:

An accretionary feature consisting of a long, low lying, narrow strip of (gravelly) sand, typically up to 4 m high and 40 to 400 m wide, often shelly, deposited in the form of wave-built beach ridge on a swampy, deltaic, or alluvial coastal plain of fine sediment.

This is the common definition for Chenier, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

Chenier plain

A chenier plain is a strand plain consisting of long, narrow beach ridges (cheniers) and intervening mudflats with marsh or swamp vegetation. The word chenier is derived from the Cajun French word, chène, meaning oak, the dominant tree growing on the crests of cheniers in southwestern Louisiana. Often, relict cheniers can be observed as a series of coast-parallel ridges in the landscape, separated by muddy soil and/or peat[1]. They are easily distinguishable because of their higher elevation and different composition, generating a striking contrast to their surroundings. Consequently, they are often used for roads, dikes and settlements.

Cheniers serve as a natural barrier that protects the shoreline from wave erosion. Coastal areas protected by cheniers provide better growth conditions for mangroves than areas without such protection[2]. Cheniers promote the formation of a mud bed on the landward side that also absorbs wave energy. Cheniers, mangroves and mud deposits together play an important role in stabilizing the shoreline.

Chenier occurrence

Cheniers are commonly found on gently sloping coasts characteized by a low to moderate wave-energy climate[3]. Chenier plains are associated with prograding littoral environments or deltas with an ample supply of fine sediments. Extensive chenier plains exist along the coasts of Louisiana (USA) and Surinam-Guyana and in the deltas of the Huanghe and Changjiang rivers in East China. Chenier plains are found on many other mud coasts, for example the Red River delta (Vietnam), central Java, Guinée and Sierra Leone. The tidal range is not a discriminating factor for the occurrence of chenier plains.

Chenier formation

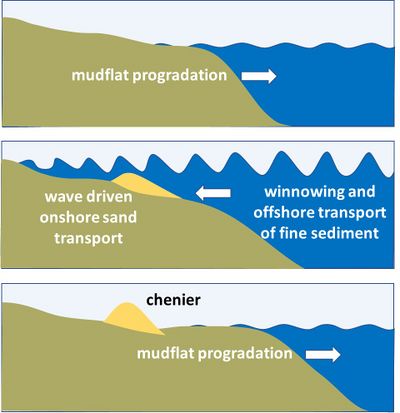

Chenier formation depends on a specific balance between wave action and sediment availability and is generally episodic[6], see Fig. 2. Contrary to beach ridges found on sandy shores, which are built from material similar in composition to the adjacent beach and shoreface, the volume of a chenier is limited by the availability of coarser particles in the otherwise muddy shoreface[7]. Under energetic (but not necessarily extreme) wave conditions, mud is gradually washed out of the seabed which initially consists of a mixture of mud with some coarser sediments (sand, possibly including shell fragments). Onshore transport of the resulting sandy top layer over the muddy substrate is in first instance promoted by waves and tidal currents, with an important role of wave asymmetry[8]. Building of a berm crest above spring tide or storm surge level takes place under average storm conditions by washover processes[3][8]. Due to the limited availability of coarse sediments, cheniers do not build up high. Only in rare occasions can cheniers grow further in volume and elevation. The landward migration may end when the chenier has reached the landward limit of onshore sediment transport or when a new chenier develops seaward on the prograding mudflat[3].

In other deltaic conditions, sandy ridges develop at the mouths of delta distributaries, where they shelter erosional backwaters that are subsequently filled with mud. These depositional chenier plains are typical of the Danube and Rhone deltas[9].

Related articles

- Coastal mud belt

- Dynamics of mud transport

- Sediment deposition and erosion processes

- Characteristics of muddy coasts

- Coastal and marine sediments

References

- ↑ Russell, R.J. and Howe, H.V. 1935. Cheniers of southwestern Louisiana. Geogr. Rev. 25: 449-461

- ↑ van Bijsterveldt, C.E.J., van der Wal, D., Mancheno, A.G., Fivash, G.S., Helmi, M. and Bouma, T.J. 2023. Can cheniers protect mangroves along eroding coastlines? – The effect of contrasting foreshore types on mangrove stability. Ecological Engineering 187, 106863

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Augustinus, P.G.E.F. 1989. Cheniers and chenier plains: a general introduction. Mar. Geol. 90: 219–229

- ↑ Hoyt, J.H. 1969. Chenier versus barrier, genetic and stratigraphic distinction. Bull. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. 53: 299-306

- ↑ Penland, S. and Suter, J.R. 1989. The geomorphology of the Mississippi River Chenier Plain. Marine Geology 90: 231–258

- ↑ Otvos, E.G. and Price, W.A. 1979. Problems of chenier genesis and terminology - an overview. Mar. Geol. 31: 251–263

- ↑ Anthony, E.J., Brunier, G., Gardel, A. and Hiwat, M. 2019. Chenier morphodynamics on the Amazon-influenced coast of Suriname, South America: implications for beach ecosystem services. Front. Earth Sci. 7: 1–20

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Tas, S. A. J., van Maren, D. S. and Reniers, A. J. H. M. 2022. Chenier formation through wave winnowing and tides. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 127, e2022JF006792

- ↑ Nardin, W. and Fagherazzi, S. 2018. The role of waves, shelf slope, and sediment characteristics on the development of erosional chenier plains. Geophysical Research Letters 45: 8435–8444

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|