GIFS activity 1.2: Case study Arnemuiden

Arnemuiden (the Netherlands): If and how coastal governance structures can actually support Inshore Fisheries (and the economics related to that)

Contents

Overview and Background

The sandy coastline of the Netherlands borders the southern part of the North Sea between Denmark and Belgium. The total length of the Dutch coastline is about 400km, divided in three units: the Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt estuary in the SW part, coastal barriers in the central part and the Wadden Islands (Schiermonnikoog, Ameland, Terschelling, Vlieland and Texel) bordering a large tidal flat area in the northern part of the country. Along the coast line, there are five coastal provinces (Zeeland, Zuid-Holland, Noord-Holland, Friesland and Groningen). The Netherlands is part of the top 5 countries with a major role in European fisheries context with 6,87 % of the total EU production of fish [1]. In 2012 the Dutch fishing fleet consisted of 740 registered vessels, with a combined gross tonnage of 133.7 thousand GT and total power of 286.5 thousand kW. In 2011, the entire fleet realized a fishing effort of 44.8 days at sea. The Dutch fleet landed a total of 261.7 kt. Jack and horse mackerels were the most important species in terms of landed weight. Sole accounted for the highest value of landings (€83 million)[2]. Fishing in the Netherlands accounts for 0.3% of the total employment. The Dutch commercial fishing fleet comprises both sea and coastal fisheries. Coastal fisheries in the Netherlands are mainly cockle fisheries, seed mussel fisheries, oyster cultures and shrimp fisheries in the Eastern and Western Scheldt, the Grevelingen, the Voordelta and the Wadden Sea [3]. Inshore fisheries was in place in 15 Dutch fishing communities, from Arnemuiden until Zoutkamp. Each of the inshore fishing communities developed a certain specification, together with specific type of fishing vessel [4].

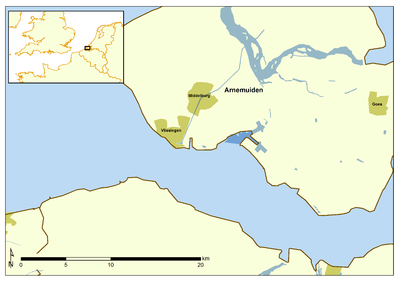

Geographical location

Governance, organisations and their objectivesIn the Netherlands, the Ministry of Economic affairs has jurisdiction over the Dutch fisheries sector. Regulations for fisheries are based on the Fisheries law of May, 30 1963. The Fisheries Management board of the Ministry has the task to manage matters concerning the production, marketing, price setting and processing of fisheries products within the CFP framework. The Fisheries Management board translates, together with the Ministry’s Legal Planning Office, policies into national fisheries policies. In this legislative process, the Government and Parliament together determine the constitutionality of proposed laws under consideration [3]. The Community Board of Fish and Fish Products (Productschap Vis), an economic sector of the corporate publiekrechtelijke bedrijfsorganisatie (PBO), deals with management of quotas, fish trade and fish processing in the Netherlands. Tasks concerning the enforcement of EU and national control measures are given to the Dutch general inspectorate, Algemene inspectiedienst (AID). In the Dutch territorial sea (between 0 and 12 nautical miles), fisheries is partly regulated by the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) and mainly regulated by a national policy [7]. Inshore fisheries are all fishery activities taking place in inshore waters; the Eastern and Western Scheldt, the Wadden Sea, the Dutch part of the Eems-Dollard estuary, the Brouwershavense Gat, the Zeegat and Goeree. Also the Voordelta and the Grevelingen lake are, as inland waters, part of the inshore fisheries policy. All waters within the 12 nm zone that are not described above are fishing zones. Within the 12 nm zone, only vessels with an engine power of <221 kW are allowed [7]. The Dutch sea fisheries policy is based on the CFP however the Netherlands have their own responsibilities for realizing the goals of the CFP. This is the case since 1992 when the Netherlands introduced a co-management system, the so called Biesheuvel groups, to regulate the national quotas. This co-management system wants to promote resource-user participation in fisheries management by means of creating incentives for fishermen to voluntarily organize themselves via producers organizations (PO) into regional groups of corporate personality [3]. The Biesheuvel system consist of private fisher’s associations formed by the Steering Committee Biesheuvel (named after the former Prime Minister Barend Biesheuvel). There are eight Biesheuvel groups in the Netherlands;, Group Delta/Zuid, Group Texel, Group Nieuwe Diep, Group PO-Oost, Group PO-Wieringen, Group Nederlandse Vissersbond I, Group Nederlandse Vissersbond II; and Group Nederlandse Vissersbond III. The associations enforce control at the fishers’ level by means of mandatory auctioning. Within these groups, fishers can communicate with each other and rent and/or barter individual quotas and sea-days [3] [8]. In the Dutch part of the North Sea, recreational fisheries mainly consist of sea anglers (the Royal Dutch Angling Association counts over 450.000 members (Sportvisserij Nederland)) [9]. It is not allowed to use non-angling fishing gear for recreational purposes in inland waters. Since 2011 the use of non-angling fish gear (gill nets, fyke nets and long-lines) by recreational fishers in marine waters has also been forbidden. However, the future of the recreational gillnet fishery in coastal waters is currently under review by the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality [9]. On behalf of the Ministry of Economics, Agriculture and Innovation IMARES started the Recreational Fisheries Programme in 2009. This program aims to estimate the number of recreational fishermen and their catches in the Netherlands [10]. The first results show that in 2010, the retained recreational catch for cod was significant (at least 10%) in comparison with the catches/quota for the commercial fishery. Also the first results for retained recreational catch for eel were significant, (~10-25%) in comparison with the catches for the commercial fishery in 2010 [9].

|