Oyster reef shore protection

Contents

Oyster reef ecosystem services

Oyster reefs are an example of biogenic reefs. Biogenic reefs are structures built with ecosystem engineer species that sustain themselves with self-generative properties. If properly designed, these reefs can fulfil a shore protection function by attenuating incident waves.

Oyster beds that were common in coastal waters in the past have largely disappeared[1]. Overharvest is the mean reason for the disappearance of oyster reefs, but other factors have also contributed, such as diseases, non-native species invasions, alterations of shorelines, changes in freshwater inflows and increased loadings of sediments, nutrients and toxins. With the disappearance of oyster reefs, many ecosystem services have been lost, including water purification, denitrification, enhancement of fish stocks, carbon sequestration, enrichment of biodiversity and ecosystem stability[2]. Oyster reefs protect sedimentary coasts from erosion by attenuating waves and trapping sediment.

Oyster reef restoration

The recent restoration of oyster reefs has been largely motivated by the coastal protection function they can perform, reducing the need for hard artificial structures. Oysters naturally aggregate and attach themselves to older shells, rocks, or submerged surfaces, creating a rocklike reef structure. The development of oyster reefs can be stimulated by creating an appropriate substrate, for example limestone or concrete or loose shells within a rigid frame[3] (Fig. 1). Oyster reefs not only reduce coastal erosion by waves and currents, but also offer a habitat for many species (e.g. algae, sponges, crustacea, finfish) and serve as a highly valued food source.

Compared with hard engineering structures, oyster reefs can respond dynamically to sea level rise as oysters grow, thereby increasing the resilience of coastal zones to climate change. However, oyster reefs cannot replace revetments for providing protection against flooding during storm surges as they do not grow around or above high tide[4][5]. A critical threshold for intertidal oyster reef establishment is 50% inundation duration. An evaluation of oyster reef restoration projects on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States revealed that a suitable oyster habitat requires inundation more than one-half of the time, which reduces the effectiveness of wave attenuation[6]. Other requisites for reef growth include appropriate water salinity, dissolved oxygen, substrate type, and well-timed larval supplementation[7][8]. Many of the living shoreline projects with oyster reefs have failed because ecological and engineering requirements were not met[6].

Appendix Wave attenuation formula

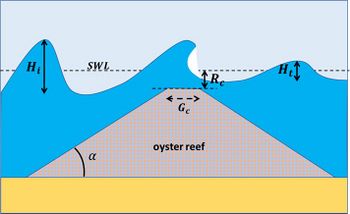

Oyster reefs can function as low-crested breakwaters (submerged or partially submerged) that dissipate part of the incident wave energy. Wave attenuation is caused by wave breaking, reflection, overtopping, and frictional dissipation. It can be expressed by means of the wave transmission coefficient [math]K_t = H_t / H_i[/math], where [math]H_i[/math] is the spectral wave height of the incoming wave (approximately equal to the significant wave height, see Statistical description of wave parameters) and [math]H_t[/math] the spectral height of the transmitted wave.

A laboratory experiment was carried out by Xiang et al. (2024[9]) with a trapezoidal shaped oyster reef built with shells (average dimensions of 7.96 cm length, 5.55 cm width, and 1.60 cm thickness). The porosity of the oyster shells, determined by measuring the volume of the water that filled the gaps among the shells, was found to be 0.67. The slope of the reef structure was [math]\tan\alpha = 0.2[/math]. The wave attenuation by this submerged oyster reef could be represented by the formula

[math]K_t \equiv \Large\frac{H_t}{H_i}\normalsize = c_1 \Big( 1 - 0.9 \, \large e^{ \frac{R_c}{H_i}\normalsize} \Big) + c_2 \Big( \large\frac{G_c}{H_i} \Big)^{c_3} \normalsize \big[1 - \large e^{c_4 \xi} \normalsize \big] \, , \quad -4.3 \lt \large\frac{R_c}{H_i}\normalsize \lt 0 \, , \qquad (1) [/math]

with coefficients [math]c_1=0.67, \; c_2=0.51, \; c_3=-0.65, \; c_4=-0.41[/math]. The meaning of the symbols in Eq. (1) is (see Fig A1):

- [math]R_c =[/math] the freeboard, distance between the reef crest level and the still water level (wave-averaged, negative for a submerged reef, positive for an emerged reef)

- [math]G_c =[/math] the width of the reef crest

- [math]\xi = \Large\frac{\tan \alpha}{\sqrt{H_i / L}} = [/math] the surf similarity parameter.

- [math]L = g T_p^2 / (2 \pi) =[/math] the wavelength of the incident wave

- [math]T_p =[/math] the peak spectral wave period

- [math]g =[/math] the gravitational acceleration

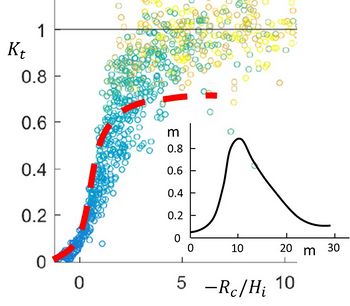

The general applicability of Eq. (1) is limited, because oyster reefs in the field can take different shapes, with different surface roughness and porosity. The experiments by Xiang et al. suggest that the wave attenuation can be substantially increased by incorporating macro-roughness elements (concrete blocks) in the oyster reef. Fig. A2 compares the prediction of Eq. (1) with the measured wave transmission over an oyster reef in the Eastern Scheldt[10]. The measured wave attenuation is larger than the prediction when the water level is close to the reef crest ([math]-1 \lt R_c/H_i \lt 0[/math]) and smaller for water levels far above ([math]R_c/H_i \lt -4[/math]). The crest freeboard [math]R_c[/math] varies with tidal rise and fall. The wave attenuation is poor at high tide in situations with strong tides.

As the oysters grow, the reef surface height, the surface area and the surface roughness increase, which enhances wave attenuation. Oyster reefs may therefore dynamically adjust to sea level rise.

Many different designs of artificial oyster reefs have been tested in the laboratory and in practice, including oyster shell bags, shell gabions and different types of structures consisting of a concrete frame for oyster attachment[11]. Shell-filled oyster bags are particularly effective for wave attenuation due to the tight shape and small porosity. Nowadays biodegradable bags are often used that slowly degrade as live oysters colonize the introduced shells, creating a stable and self-sustaining oyster reef[12].

Oyster bag reefs were investigated by Provan et al. (2024[12]) through flume experiments at 1:1 scale. They found satisfactory agreement with the empirical formula established by van Gent et al. (2023[13]) for wave transmission by low-crested breakwaters,

[math]K_t = c_5 + c_1 \tanh \Bigg(c_4 - \Large\frac{R_c}{H_i}\normalsize - c_2 \bigg( \Large\frac{G_c}{L} \bigg)^{c_3} \normalsize \Bigg) , \qquad (2)[/math]

with [math]c_1=0.34, \; c_2=3.1, \; c_3=0.75, \; c_4=-0.3, \; c_5=0.58 [/math].

They also tested the stability of reefs made of 3 bags (1 on top of the 2 others) and 5 bags (2 on top). The stability depended primarily on the relative freeboard [math]R_c/H_i[/math] and the surf similarity parameter [math]\xi[/math]. The stability was lowest for freeboard values [math]R_c[/math] close to zero (giving the lowest value of the stability parameter [math]N[/math], see Stability of rubble mound breakwaters and shore revetments). Stability increased for decreasing values of the surf similarity parameter.

Related articles

- Wave transmission by low-crested breakwaters

- Nature-based shore protection

- Artificial reefs

- Restoration of estuarine and coastal ecosystems

References

- ↑ Beck, M.W., Brumbaugh, R.D., Airoldi, L., Carranza, A., Coen, L.D., Crawford, C., Defeo, O., Edar, G.J., Hancock, B., Kay, M.C., Lenihan, H.S., Luckenbach, M.W., Toropova, C.L., Zhang, G. and Guo, X. 2011. Oyster reefs at risk and recommendations for conservation, restoration, and management. Bioscience 61: 107–116

- ↑ Grabowski, J.H., Brumbaugh, R.D., Conrad, R.F., Keeler, A.G., Opaluch, J.J., Peterson, C.H., Piehler, M.F., Powers, S.P. and Smyth, A.R. 2012. Economic Valuation of Ecosystem Services Provided by Oyster Reefs. BioScience 62: 900–909

- ↑ Goelz, T., Vogt, B. and Hartley, T. 2020. Alternative substrates used for oyster reef restoration: a review. Journal of Shellfish Research 39: 1–12

- ↑ Scyphers, S.B., Powers, S.P., Heck, K.L. and Byro, D. 2011. Oyster Reefs as Natural Breakwaters Mitigate Shoreline Loss and Facilitate Fisheries. PLoS ONE 6 (8), e22396

- ↑ Borsje, B.W., van Wesenbeeck, B.K., Dekker, F., Paalvast, P., Bouma, T.J., van Katwijk, M.M. and de Vries, M.B. 2011. How ecological engineering can serve in coastal protection. Ecol. Eng. 37: 113–122

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Morris, R.L., La Peyre, M.K., Webb, B.M., Marshall, D.A., Bilkovic, D.M., Cebrian, J., McClenachan, G., Kibler, K.M., Walters, L.J., Bushek, D., Sparks, E.L., Temple, N.A., Moody, J., Angstadt, K., Goff, J., Boswell, M., Sacks, P. and Swearer, S.E. 2021. Large-scale variation in wave attenuation of oyster reef living shorelines and the influence of inundation duration. Ecol. Appl. 31, e02382

- ↑ Theuerkauf, S.J. and Lipcius, R.N. 2016. Quantitative validation of a habitat suitability index for oyster restoration. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 64

- ↑ Chowdhury, M.S.N., La Peyre M., Coen, L.D., Morris, R.L., Luckenbach, M.W., Ysebaert, T., Walles, B., Smaal, A.C. 2021. Ecological engineering with oysters enhances coastal resilience efforts. Ecological Engineering 169, 106320

- ↑ Xiang, T., Bryski, E. and Farhadzadeh, A. 2024. An experimental study on wave transmission by engineered plain and enhanced oyster reefs. Ocean Engineering 291, 116433

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Sigel, L., 2021. Effect of an Artificial Oyster Reef on Wave Attenuation. MSc Thesis. TU Delft University of Technology

- ↑ Xu, W., Tao, A., Wang, R., Qin, S., Fan, J., Xing, J., Wang, F., Wang, G. and Zheng, J. 2024. Review of wave attenuation by artificial oyster reefs based on experimental analysis. Ocean Engineering 298, 117309

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Provan, M., Rahman, A. and Murphy, E. 2024. Full-scale experiments on wave transmission and stability of oyster shell-filled bag berms. Coastal Engineering 193, 104578

- ↑ van Gent, M.R.A., Buis, L., van den Bos, J.P. and Wüthrich, D. 2023. Wave transmission at submerged coastal structures and artificial reefs. Coastal Engineering 184, 104344

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|