Governance policies for a blue bio-economy

A blue bio-economy aims to optimize the development and utilization of coastal and marine ecosystem services for the benefit of society in a market context. The concept of ecosystem services considered here is elaborated in the article Ecosystem services.

Contents

Pricing of ecosystem services

The free market economy does not guarantee that optimal use is made of the services that ecosystems potentially provide[1]. Ecosystem services that benefit a specific group of users can (and in most cases will) be developed and enhanced through market mechanisms, to the extent that user value exceeds the production costs. This is less the case for ecosystem services that benefit society in general; without government intervention, these services are usually either underdeveloped or compromised by overexploitation (the 'Tragedy of the Commons').

Government intervention is also necessary when the market price of ecosystem services does not take into account the social costs of negative side effects associated with these services. The unpriced side effects associated with the utilization of ecosystem services are called externalities; externalities can be positive, but more often they are negative. A positive externality is the provision of regulatory or cultural services associated to an ecosystem service driven by market demand (see Ecosystem services). Pollution and habitat degradation are examples of negative externalities. Evaluating the net societal impact of the marketing of ecosystem services on the coastal and marine environment is not always obvious, because impacting activities generally have beneficial effects on some environmental aspects and detrimental effects on others. Several methods have been developed to set a price on coastal and marine ecosystem services, see e.g. Multifunctionality and Valuation in coastal zones: concepts, approaches, tools and case studies and other articles in the category Evaluation and assessment in coastal management. Although there is no unique unambiguous method, we will assume here that it is possible to assess whether the net societal effect of externalities is beneficial or detrimental.

Categories of ecosystem services

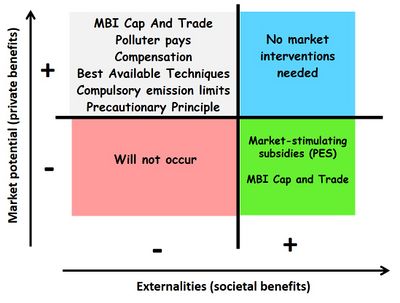

The type of intervention that is most appropriate and effective depends on the type of ecosystem service and on local social and cultural conditions. Some principles have been elaborated by Hasselström and Gröndahl (2021)[2] for eutrophication reduction and carbon storage issues. These principles can also be applied for other ecosystem services. They distinguish four categories of ecosystem services based on the market value [math]M[/math] of the ecosystem service, the production costs [math]P[/math] and the net societal impact [math]E[/math] of the externalities associated with the utilization of the ecosystem service. The net societal impact (sum of associated beneficial and detrimental externalities) can be positive or negative. The four categories of ecosystem services, illustrated with some possible examples, are:

- [math]E\gt 0, \quad M\gt P . \quad[/math] Positive net societal impact, market value exceeds production costs

Possible examples (only positive externalities indicated):

M = Promoting beach tourism, P = Beach nourishment and sewage treatment, E = Coastal protection, ecosystem health

M = Food provision, P = Farming of molluscs in eutrophic waters, E = Reduction of excess nutrients

M = Medical applications, P = Seaweed farming, E = Reduction of excess nutrients

M = Protection of coastal assets, P = Restoration of mangrove forests, E = contribution to carbon sequestration and other ecosystem services - [math]E\lt 0, \quad M\gt P . \quad[/math] Negative net societal impact, market value exceeds production costs

Possible examples (only negative externalities indicated):

M = Food provision, P = Fishery, E = Foodweb disturbance (e.g. trophic cascade effects), habitat degradation / loss, biodiversity loss and species extinction (see Effects of fisheries on marine biodiversity)

M = Coastal tourism, P = Real estate development, E = Habitat degradation, landscape alteration

M = Shipping, P = Canalization of estuaries, E = Loss of habitats and associated ecosystem functionalities - [math]E\gt 0, \quad M\lt P. \quad[/math] Positive net societal impact, market value lower than production costs

Possible examples (only positive externalities indicated):

M = Food provision, P = Harvesting invasive species (e.g. jellyfish), E = Foodweb restoration

M = Renewable energy, P = Biomass of seaweed cultivation, E = Carbon sequestration, biofertilizer and other ecosystem services (see Seaweed (macro-algae) ecosystem services)

M = Non-marketable services, e.g. water quality, landscape, P = restoration coastal wetlands, E = contribution to carbon sequestration, biodiversity and other ecosystem services - [math]E\lt 0, \quad M\lt P . [/math] Negative net societal impact, market value lower than production costs

Policy instruments for a blue bio-economy

The categories 1 and 4 do not need any governmental intervention. Category 1 will normally occur in a liberal market and delivers net beneficial side effects to society. However, the benefit of category 1 ecosystem services for society can possibly be enhanced. Targeting government subsidies to ecosystem service providers to increase the benefit of positive externalities is an option, but entails the risk of spending public money on services that would have been provided anyway[2]. Labels securing that the ecosystem service has been produced without harm to the environment, so-called eco-certification, are a market-based instrument to limit possible detrimental side effects. The higher price consumers are ready to pay for certified products generates an incentive for producers to take all necessary measures to prevent any environmental damage their activities could cause[3].

Category 4 will not happen in a liberal market economy.

Category 2 will normally occur in a liberal market economy, but the negative side effects may be considered socially unacceptable. Several types of governmental intervention can address this issue:

- Setting a legally binding and enforceable limit on the production of negative side effects or the obligation to completely phase out certain negative side effects. Such an intervention is in line with the Precautionary Principle. Although emission standards for polluting substances exist in many countries, enforcement is often insufficient to ensure full compliance[4].

- Obligation to apply the Best Available Techiques (BAT) or Best Available Techniques Not Entailing Excessive Costs (BATNEEC). BAT and BATNEEC are key elements of environmental laws in many countries around the world, especially for setting emission limit values and other permit conditions in preventing and controlling industrial emissions[5].

- Compensatory measures. Under EU law, actors carrying out activities that cause harm to protected species or protected habitats that cannot reasonably be avoided are obliged to take compensatory measures that neutralize these environmental adverse effects.

- The polluter pays principle (PPP). The user of the ecosystem service is obliged to pay a tax or fine for repairing any damage caused to the environment. This principle, when applied to companies that make use of ecosystem services, generates a strong incentive for these actors to mitigate negative side effects. The PPP can be extended to include assurance or performance bonds, which are an economic instrument to ensure that the worst case cost of damage is covered. Assurance premiums provide an incentive to limit impacts and to repair any damage the activity has produced. For example, lower insurance costs for the use of more environmentally friendly fishing gear provide added incentive for their earlier adoption and development[6].

- Market-Based Instruments (MBI). The most commonly applied MBI is CAT - Cap and Trade (not to be confused with Common Asset Trust), based on tradable allowances (emission rights) to cause a certain amount of environmental damage over a certain period of time. CAT encourages actors to take mitigation measures and sell permits that are no longer needed, so that emissions can be allocated where mitigation measures are most costly. Reduction of environmental damage is achieved by limiting the number of allowances. Ensuring actors do not exceed their allowances is crucial for the credibility of the CAT mechanism and requires rigorous monitoring and validation. CAT is implemented in practice to reduce CO2 emissions via the so-called ETS - Emission Trading System. Measures to remove emitted pollutants from the environment (compensation schemes, e.g. carbon sequestration) are promoted in the ETS by granting tradable allowances to such measures (see Blue carbon sequestration). Other applications of CAT are conceivable, for example as a way to reduce the emission of nutrients[2]. In the fishing industry, tradable fishing rights are referred to as Individually Transferable Quotas (ITQ), the right to harvest a certain proportion of the total allowable catch (TAC). ITQs represent catch shares where the shares are transferable; shareholders have the freedom to buy, sell and lease quota shares. As the economic value of quota shares increases when fish stocks are well managed (higher TAC), ITQ shares create an economic incentive for environmental stewardship. However, ITQs do not exclude 'free-riding' behavior[7].

Category 3 ecosystem services will not normally be taken up in a liberal market economy, even if they provide significant societal benefits. Financial compensation is needed here to promote the development or strengthening of these ecosystem services. Instruments are:

- PES - Payment for Ecosystem Services. Government subsidies (PES) can give service providers the necessary incentives to develop or strengthen these ecosystem services, provided the financial compensation is at least equal to the production costs of the service. In some cases, PES grants are awarded by private parties if the ecosystem service delivers benefits to their business. PES grants are conditionally linked to the delivery of agreed ecosystem services and should not exceed the value of the ecosystem services provided[8]. PES differs from PPP (public-private partnership) in that the subsidized ecosystem service benefits to society (no exclusive exploitation rights).

- CAT - Cap and Trade. Ecosystem services that mitigate the impact of environmental damage by economic activities can be (co)financed by selling allowances for a certain amount of damage. It requires the existence or the creation of a CAT market for this type of damage. This is the case for the greenhouse gas Emission Trade System, which can provide credits for local blue carbon projects to enhance carbon sequestration in coastal wetlands, e.g. mangrove forests, salt marshes, seagrass meadows (see Blue carbon sequestration). An international organization (Verra) has established generally accepted Verified Carbon Standards for certifying blue carbon projects through assessment of the amount of sequestered carbon. The potential of blue carbon financing of coastal wetland creation, conservation and maintenance is currently largely unused[9]. Increase of the market price of carbon credits will provide a strong stimulus for blue carbon projects[10]. Verified blue carbon projects can be (co-)financed by selling credits on the international market, or they can be government funded to meet national targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. However, the high costs associated with labor-intensive carbon measurement and monitoring for blue carbon certification are a concern for small-scale projects, for which PES funding or other funding schemes may be preferred[11].

A blue bioeconomy would also be boosted by the establishment of an international trading system for nutrient offset credits. In this way, financial resources could be raised for the restoration and maintenance of coastal habitats that provide other ecosystem services in addition to eutrophication mitigation. Currently (2022) there are few initiatives to develop market-based tools for nutrient offsetting and other ecosystem services in coastal areas[2].

Governance policies fostering a blue bio-economy discussed in this article are summarized in Fig. 1.

Related articles

- Ecosystem services

- Blue carbon sequestration

- Multifunctionality and Valuation in coastal zones: concepts, approaches, tools and case studies

- Seaweed (macro-algae) ecosystem services

References

- ↑ Austen, M.C., Andersen, P., Armstrong, C., Döring, R., Hynes, S., Levrel, H., Oinonen, S., and Ressurreiçao, A. 2019. Valuing marine ecosystems - taking into account the value of ecosystem benefits in the blue economy. In: Future Science Brief 5 of the European Marine Board. Ostend, Belgium, ISBN 9789492043696. ISSN: 4920-43696

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Hasselström, L. and Gröndahl, F. 2021 Payments for nutrient uptake in the blue bioeconomy – When to be careful and when to go for it. Marine Pollution Bulletin 167, 112321

- ↑ Froger, G., Boisvert, V., Méral, P., Le Coq, J-F., Caron, A. and Aznar, O. 2015. Market-Based Instruments for Ecosystem Services between Discourse and Reality: An Economic and Narrative Analysis. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11595-11611

- ↑ Giles, C. 2020. Next Generation Compliance: Environmental Regulation for the Modern Era Part 2: Noncompliance with Environmental Rules Is Worse Than You Think. Harvard Law School, Environmental And Energy Law Progam

- ↑ OECD 2017. Report on OECD project on best available techniques for preventing and controlling industrial chemical pollution activity: policies on BAT or similar concepts across the world. Health and Safety Publications Series on Risk Management No. 40 ENV/JM/MONO(2017)12

- ↑ Innes, J., Pascoe, S., Wilcox, C., Jennings, S. and Paredes, S. 2015. Mitigating undesirable impacts in the marine environment: a review of market-based management measures. Front.Mar.Sci. 2:76

- ↑ Garrity, E.J. 2020. Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQ), Rebuilding Fisheries and Short-Termism: How Biased Reasoning Impacts Management. Systems 2020, 8, 7

- ↑ Wunder, S. 2015. Revisiting the concept of payments for environmental services. Ecological Economics 117: 234-243

- ↑ Macreadie, P.I. et al. 2022. Operationalizing marketable blue carbon. One Earth 5: 485-492

- ↑ Zeng, Y., Friess, D.A., Sarira, T.V., Siman, K. and Koh, L.O. 2021. Current Biology 31: 1–7

- ↑ Friess, D.A., Howard, J., Huxham, M., Macreadie, P.I. and Ross, F. 2022. Capitalizing on the global financial interest in blue carbon. PLOS Clim 1(8): e0000061

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|