Effect of Climate Change in the Baltic Sea Area

Contents

Baltic Sea – background information

The Baltic Sea is a relatively shallow sea in north-eastern Europe, surrounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of central and east Europe and the Danish islands. It is connected with North Sea through the Kattegatt, Øresund, the Great Belt and the Little Belt. It covers area of about 415 000 km2 and its average depth is 55 m. The central part of the Baltic Sea is known as Baltic Proper, other large parts which might be distinguished are the Bothnian Bay, the Bothnian Sea, the Gulf of Finland, the Gulf of Riga, and the Gulf of Gdansk, the Bornholm and Arkona basins, followed by the Sound, the Belt Sea and the Kattegat.

Baltic Sea Area

The term Baltic Sea Area is usually used to denote the Baltic Sea drainage basin. The Baltic catchment includes territories from 14 states (nine countries bordering to the sea and five other countries: Belarus, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Norway and Ukraine) and has total land area of approximately 1.7 million km2. About 16 million people live on the coast, and around 85 million in the entire catchment area of the Baltic Sea. More than 200 large rivers flow into the Baltic bringing around 480 km3 of freshwater annually. That makes the Baltic Sea the largest brackish water body in the world. Among many others the biggest rivers entering Baltic are Neva, Vistula, Oder, Neman, Daugava. See also Baltic Sea.

Past climate in the Baltic Sea Area

Climate models predict a 2-4ºC rise in water temperature along with a rise in sea levels in the current century. This will have major implications for species, ecosystems and food webs.

The MarBEF project MarFISH examined archaeological evidence from the waters around Denmark (the Kattegat, Skagerrak, the Belt Sea and Bornholm) during a warm period from 7000-3900BC and showed that, during this period, there were several warm-water fish species present.

These species were: smoothhound (Mustelus sp.), common stingray (Dasyatis pastinaca), anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus), European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), black sea bream (Spondyliosoma cantharus) and swordfish (Xiphias gladius).

These species currently have a more southerly distribution and their presence near Denmark in the past was presumably caused by the warmer temperatures at that time. However, fishermen in this area are now capturing commercially important quantities (tens and thousands of tonnes) of some of these species. This is mainly the case for small-sized southern species while large, northern species have shifted their distributions to more northern and deeper waters. These changes have also been seen in scientific fisheries surveys which annually monitor the species composition of the North Sea fish community[2].

During the substantially colder climate in the 17th century, the herring Clupea harengus membras fishery in the North East Baltic Sea (Gulf of Riga) mostly took place during the summer months (June-July). This was probably because the fish migrated later to the spawning areas close to the coast where they were caught. In contrast, nowadays, in much warmer climate conditions, the coastal trapnet herring fishery in spawning grounds takes place a few months earlier[2].

Recent climate change in the Baltic Sea Area

Two major climate types dominate in much of the Baltic Sea Area:

- Most of middle and northern areas are determined by the temperate coniferous-mixed forest zone with long, cold, wet winters, where mean temperatures of warmest month is no lower than 10°C and that of the coldest month is no higher than −3°C, and where the rainfall is, on average, moderate in all seasons;

- Much of the southwestern and southern areas belong to the marine west-coast climate, where prevailing winds constantly bring in moisture from the oceans and the presence of a warm ocean current provides for moist and mild winters, with frequent thawing periods even in mid-winter.[3]

Examples of other effects on phenolgy

Temperature trends over the Baltic Sea Region

The annual warming trend for the Baltic Sea basin is about 0.08°C/decade. This is higher than the worldwide trend which is about 0.05°C/decade. This warming trend can be observed as a decrease in the number of very cold days during winter as well as a decrease in the duration of the ice cover and its thickness in many rivers and lakes, particularly in the eastern and southeastern Baltic Sea basin. Furthermore, an increasing length of the growing season in the Baltic Sea basin has been observed during this period.

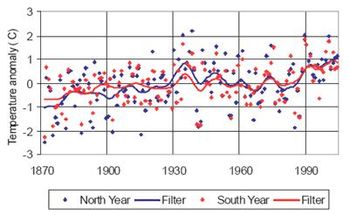

In the 20th century, temperatures in the Baltic Sea basin increased during the early part of the century (termed the early 20th century warming) until the 1930s; then there was a slightly cooler period till 1960s, followed by another warming period continuing today (Figure 3).

Warming is characterized by a pattern where mean daily minimum temperatures have increased more than mean daily maximum temperatures. The strongest warming trend is observed in spring whilst wintertime temperature increase is irregular but larger than in summer and autumn. The climate warming is reflected also in time series data on the maximum annual extent of sea ice and the length of the ice season in the Baltic Sea. Regarding the ice extent, the shift towards a warmer climate took place in the second half of the 19th century. The length of the ice season showed a decreasing trend by 14–44 days during the 20th century, the exact number depending on the location around the Baltic Sea.[4]

Precipitation trends

The external water budget of the Baltic Sea is dominated by water import from river discharge, exchange with North Sea water, and net precipitation (precipitation minus evaporation). Water inflow from North Sea is very limited and only Kattegat deep water contributes to the Baltic Sea water renewal. Taking into account freshwater supply the estimated residence time of water in Baltic Sea is about 33 years. Recent observations have provided an estimate (for the past 30 years) of mean annual precipitation of 750 mm/year for the entire Baltic Sea basin, including both land and sea. The highest precipitation occurs in the mountain regions in Scandinavia and southern Poland, while the lowest amounts of precipitation occur in the northern and northeastern part of the basin as well as over the central Baltic Sea. Precipitation has increased on average but there is no uniform spatial distribution of this increase. Within the Baltic Sea area the largest increase has occurred in Sweden and the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea. Seasonally largest increases have occurred in winter and spring. Changes in summer are characterized with increases in the northern and decreases in the southern parts of the Baltic Sea basin. Winters are projected to become wetter in most of the Baltic Sea basin and summers to become drier in southern areas for many scenarios. Northern areas could generally expect winter precipitation increases of about 25% to 75%, while the projected summer changes lie between 5% and 35%. Southern areas could expect increases ranging from about 20% to 70% during winter, while summer changes would be negative, showing decreases of as much as 45%. Taken together, these changes lead to a projected increase in annual fresh water inflow for the entire basin.[4]

Projected climate change effects

Salinity and temperature

A lowering of salinity (due to generally higher precipitation and river discharge) is thought to have a major influence on the distribution, growth and reproduction of the Baltic Sea fauna. The salinity is already so low today that some fish species have adapted their physiology to be able survive. Freshwater species are expected to enlarge their significance, and invaders from warmer seas (such as the zebra mussel Dreissena polymorpha or the North American jelly comb Mnemiopsis leidyi) are expected to enlarge their distribution area.[4] If climate change leads to a further decrease in Baltic Sea salinity, this will reduce the number of marine fish species, even though one might otherwise predict that the increasing temperature should allow warm water-adapted species to immigrate. The Baltic Sea example shows that it will be important to consider multiple aspects of climate change, especially in coastal areas, if we are to estimate how marine biodiversity will change in future[2].

Climate change will also have non-thermal impacts on fish populations. For example, changes in the strength, direction and location of ocean currents can affect the probability that fish eggs and larvae survive and grow.

Eutrophication

Climate-induced changes in marine ecosystems would include changes in nutrient cycling and contaminant distribution and changes at all trophic levels from bacteria to seabirds and marine mammals. As temperature rises, the ability of the ocean to retain oxygen will decrease. In many coastal areas in Europe (e.g., bays, straits, estuaries) the combination of rising temperature and decreasing oxygen will lead to eutrophication, especially in areas which already also receive high levels of nutrients. This will reduce the habitat size of bottom-living fish species such as cod and flatfishes. These species will become less abundant and widespread as coastal areas experience longer and more frequent anoxic periods[2].

Sea level rise

Another impact of climate change will be the rise in sea level due to melting of land-based glaciers and the expansion of seawater as it warms up. Both factors will cause flooding of coastal lowlands. Newly flooded coastal areas can provide more fish habitat, especially for benthic juveniles stages which are common in coastal areas[2].

Adaptation to Climate Change in the Baltic Sea Region

The Baltic Sea Region faces a variety of challenges due to recently observed and projected climate changes, in particular the general trend of increasing temperature and changes in precipitation pattern. Different approaches are needed to deal with problems on regional and local scales. Some of the most important issues which require management strategies are:

- coastal protection;

- flooding events prediction and appropriate mitigation aftermath;

- water shortage.

The concepts of adaptation and mitigation related to climate change are presented in figure 4. Adaptation activities help to diminished the negative climate change impacts or exploit beneficial opportunities of climate change. Mitigation activities are concerned with strategies and measures for greenhouse gas emission reduction.[5]

Adaptation strategies to climate change impacts are hardly implemented in policies of the Baltic Sea Region countries. More detailed analyses of current and future risks are needed for development of adequate adaptation solutions. However, adaptation and mitigation approaches should not be regarded as a separate topic. They are be to integrated in different fields of policies on regional, local, national and international level.

Related articles

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 HELCOM

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Heip, C., Hummel, H., van Avesaath, P., Appeltans, W., Arvanitidis, C., Aspden, R., Austen, M., Boero, F., Bouma, TJ., Boxshall, G., Buchholz, F., Crowe, T., Delaney, A., Deprez, T., Emblow, C., Feral, JP., Gasol, JM., Gooday, A., Harder, J., Ianora, A., Kraberg, A., Mackenzie, B., Ojaveer, H., Paterson, D., Rumohr, H., Schiedek, D., Sokolowski, A., Somerfield, P., Sousa Pinto, I., Vincx, M., Węsławski, JM., Nash, R. (2009). Marine Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning. Printbase, Dublin, Ireland ISSN 2009-2539

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Climate Change in the Baltic Sea Area – HELCOM Thematic Assessment in 2007 Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings No. 111, HELCOM, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 BALTEX Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin, Göteborg 2006.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hilpert, K., Mannke, F., Schmidt-Thomé, P. (2007): Towards Climate Change Adaptation in the Baltic Sea Region, Geological Survey of Finland, Espoo.

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|