Study Cornwall and Scilly Isles

Cornwall and Scilly Isles FLAG case study

Contents

Introduction

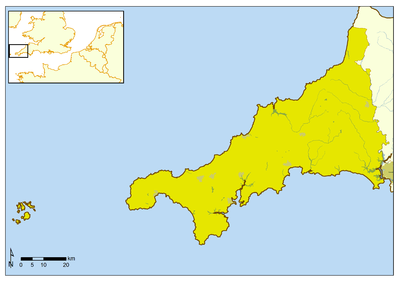

Covering the largest coastal area in any of the English FLAGs the Cornwall and Scilly Isles FLAG is 3,563 square kilometres in size (See Figure 1), and as an industry fishing employs directly over 1000 people in the region. The Cornish fishing industry is one of the most varied in the UK with over fifty different species landed and fishing practices ranging from otter trawling to crab/lobster potting, to hand lining[1]. The large mixture of gear, size of boat, catch and vast distances within and between different ports is an important consideration in developing a more inclusive management approach in this region. Fishing is an important part of the Cornish economy and as in the other case studies it makes a substantial indirect contribution to the coastal economy through the draw of the fishing boats, fresh fish to buy and eat, and the picturesque fishing villages that are so central to the identity of the region and the tourism offer.

Fisheries Governance OverviewResponding to challenges facing the industry in the region (including rising costs such fuel and licences, reduced number of new entrants, ageing demographic, increasing displacement of fishing grounds for conservation and other commercial factors, climate change, declining port/harbour infrastructure and poor market/supply chain conditions) the area secured FLAG status. FLAGs are funded by Axis 4 of the European Fisheries Fund (EFF) and are intended to support the sustainable local development of fishing industries and their related communities without increasing fishing effort. EFF is managed in the UK by the Marine Management Organisation (MMO), a non-departmental public body under the government Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Cornwall and Scilly Isles is one of six English FLAGs. This funding programme has been developed in part owing to the acknowledgement at European Commission level that fisheries in smaller communities often make a considerable contribution to direct and indirect tourism, cultural and social value[2]. Thus many of the FLAG projects focus on capitalising on these contributions through encouraging tourism and cultural fisheries related projects for example through fish festivals, heritage centres and art installations. In addition to securing a higher value for catch landed through marketing and supply chain innovation. Making fishing a more secure profession to attract the next generation of fishers has also been central to a lot of the FLAGs with investment in fisher training, in port/ beach infrastructure and other health and safety elements on the boats. EFF will be replaced with the EMFF (European Maritime and Fisheries Fund) in 2015 with a particular focus on Integrated Marine Policy (IMP). In terms of governance Cornwall Development Company is the accountable authority for the FLAG and it reports to the MMO. The FLAG has a mixture of fishing industry (fisher, fisherman’s association chairs and Harbour Masters), private and public sector stakeholders (including local authorities and national environment and conservation bodies). In terms of industry representation at a national level the fishers have the option of membership through the NFFO (National Federation of Fishermen’s Organisations); the inshore specific national association NUTFA (New Under Ten Fishermens Association); and the Shellfish Association of Great Britain (SAGB). At a regional level many of the fleet are represented by the Cornwall Fish Producers Organisation (CFPO) or the South West Handline Fishermen’s Association (SWHFA); while at a local level (to varying degrees of activity) smaller fishing and harbour associations exist to provide local fisher representation and organisation. English inshore fisheries management (operating within six nautical miles) is policed and managed by the IFCAs (Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authorities). The Cornish fleet work with the Cornwall IFCA and Isles of Scilly IFCA. The IFCAs co-operate with the MMO on several areas including fisheries enforcement and marine protected area management. IFCAs are funded through local authorities, but report to Defra. IFCAs replaced sea fisheries committees in April 2011, with an important expanded socio-economic remit to "lead, champion and manage a sustainable marine environment and inshore fisheries, by successfully securing the right balance between social, environmental and economic benefits to ensure healthy seas, sustainable fisheries and a viable industry"[3]. The MMO is responsible for regulation and licensing of fishing in England. The duties and powers of the IFCAs and the MMO are set out in the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (UK) and this takes account of European Union instrument for fisheries management the recently reformed Common Fisheries Policy or CFP[4]. The Marine and Coastal Access Act, 2009 (UK) establishes the marine planning regime for the UK including underlying ICZM principles and the designation of a network of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) (and in England Marine Conservation Zones (MCZs). Natural England (an Executive Non-departmental Public Body that is responsible for advising the UK Government on the natural environment) works with relevant stakeholders in helping inform Defra on their planning for these sites. UK fisheries management and marine planning is informed by Cefas (Centre for Environmental, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science), who are the executive agency responsible for carrying out research and monitoring of fish and shellfish stocks. [Note: This summary table provides a time-specific snap-shot of the issues observed in Winter 2013 during the research for this case study. The full context and detail of these issues can be read in the full GIFS report here: http://www.gifsproject.eu/images/pdf/GIFS_Report_Act1.2.pdf. Fisheries governance and the social processes that make up these structures are highly dynamic and this table should be read with that in mind.]

|