Open oceans

This article describes the habitat of the Open oceans. It is one of the sub-categories within the section dealing with biodiversity of marine habitats and ecosystems. It gives an overview about the characteristics, zonation, biology and threats of the open oceans. Some legal aspects are also discussed.

Contents

Introduction

The open oceans or pelagic ecosystems are the areas away from the coastal boundaries and above the seabed. It encompasses the entire water column of the seas and the oceans and lies beyond the edge of the continental shelf. It extends from the tropics to the polar regions and from the sea surface to the abyssal depths. It is a highly heterogeneous and dynamic habitat. Physical processes control the biological activities and lead to substantial geographic variability in production.

Zonation

The water column is subdivided into distinct zones by water depth and distance from shore. The distinct zones are:

- The epipelagic zone ranges from the sea surface to a depth of about 200 meters. This is also the limit of the photic zone. Light penetrates into this surface water and is usually enough for the photosynthesis.

- The mesopelagic zone lies underneath the epipelagic zone and extends to about 1,000 meters.

- The bathypelagic zone is the zone between the 1,000 and 4,000 meters.

- The abyssalpelagic zone extends to a water depth of 6,000 meters.

- The hadalpelagic zone is deeper than 6,000 meters and is found in deep-sea trenches.

Characteristics

Currents

Surface and subsurface currents causes uniform conditions of temperature, salinity, concentration of dissolved nutrients and gasses and the quantity and composition of biota on horizontal distances. This is not necessarily true in the vertical dimension. In the vertical dimension, stratification can be the result of this.

Further information about currents can be found in the article about ocean circulation.

Stratification

The water column can be stratified by density. A permanent thermocline separates the warm, buoyant surface layer from the cold, dense deep layer. The water above the thermocline is well mixed by the wind. Also the temperature, salinity and the community of organisms in this water change with the seasons. Below the thermocline, the water is isolated from the atmosphere so the temperature and salinity remain stable over the year. This water is sparsely populated with animals. [3] Besides the temperature, stratification can also be caused by differences is salinity and differences in density. The transition zone is called a halocline for the salinity and a pycnocline for the density.

Light transmission and absorption

Life depends directly or indirectly on energy from sunlight. In the ocean, marine plants use green chlorophyll and a few accessory pigments to capture the visible light from the sun. A large fraction of that sunlight is reflected from the sea surface back to the atmosphere. The remaining light enters the water and is absorbed by water molecules. Approximately 65% of the visible light in water is absorbed within 1 meter of the sea surface. This energy is converted into heat and elevates the surface water temperature. The red and yellow light (longer wavelengths λ) are absorbed by water more readily then the green and blue light (shorter wavelength λ). This is called the selective absorption of wavelengths. It accounts for the blue color of the open ocean. Very clear water let pass not even 1% of the light that enters the ocean to a depth of 100 meters. Water close to the land has high suspended solids. Because of this, light may not penetrate this turbid water deeper than 20 meters. This causes a shift to the green and yellow wavelengths, because of the reflecting wavelengths by suspended particles. Due to the characteristics of this light transmission, the water column can be divided into two distinct zones. The upper zone is called the photic zone. In this zone, plants receive adequate levels of sunlight and can photosynthesize. The zone below the photic zone is called the aphotic zone. Plants cannot survive in this dark zone.

Biology

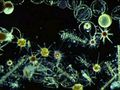

Despite the enormous size of the open ocean, it does not support a dense population of organisms in its water or on the sea bottom. This is because it is located far from land, which is the main source of the essential nutrients that organisms need to grow. The water is mixed by currents of large circulation gyres. The biomass is limited but the diversity is remarkably high. A useful parameter for delineating depth zones and the vertical distribution of the biota in it is the degree of illumination. The upper zone or photic zone is well illuminated, so plants can photosynthesize. Depending on the clarity of the water, this zone can extend to depth of 100 to 200 meters. In the temperate latitudes, heat is gained and lost during the summer and winter. Together with this, a seasonal thermocline at about 100 meters depth comes and goes. Seasonal succession of indigenous biota is also visible. The water is nutrient – poor, because of the absence of land and rivers. Plants cannot live attached to the bottom of the open ocean because there is too little light. The sparse plants that live here are entirely planktonic. The pelagic flora falls into two main groups: the unicellular microphytoplankton and the large free-floating macroalgae. Microphytoplankton consists of diatoms, dinoflagellates and coccolithophorids. The larger diatoms are grazed by large '''zooplankton''' and these are on their turn consumed by fish. Herbivorous zooplankton consists of foraminifera and radiolarian. These are consumed by larger animals such as copepods. The floating organisms (neuston) at the surface have a blue color due to the presence of protective pigments. These pigments are able to reflect the damaging part of the light spectrum (UV). This is necessary because the habitat is exposed to high levels of ultraviolet radiation. Other animals are amphipods, squids, fishes, arrow worms,… Organisms in the epipelagic such as crustaceans adopt the red colors as a mean of camouflage. This is possible because red light is absorbed rapidly and does not penetrate far into this zone. The red colors are effectively invisible at depth and this makes the organisms invisible to others.

The dysphotic zone is a zone with little light perception. The lower limit lies at a depth of approximately 500 to 1,000 meters. In this layer, an oxygen minimum is present. No seasonal effects of heating and cooling are present. This makes the zone stable and unchanging over time. Abundant organisms are crustaceans (copepods, shrimps, amphipods, ostracods and prawns). These organisms have red to red-orange pigmentation. Other animals are squids and fishes. Several adaptations have evolved to this zone. The first one is the presence of large size and light-sensing ability of the eyes. Some organisms have additional organs called photophores, which produce bioluminescence. Some fish have bacterial photophores in which light is produced by the metabolic activities of symbiontic bacteria that live in dense concentrations in the photophores. Some species engage in diurnal vertical migration to get food. They swim upward to the photic zone at night to feed and descend again during the day.

In the aphotic zone, it is constantly dark and cold. The zone begins at depths of 500 to 1,000 meters. Many species in this region are colored red or black. Organisms that occur here are copepods, ostracods, jellyfishes, prawns, mysids, amphipods, worms and fishes. Fishes at mid-depth have evolved adaptations to maximize their chances of capturing their prey. These fishes are small with enormous mouths lined with sharp teeth. Their jaws can be unhinged to eat large preys. They also have bioluminescent organs. Some species have a fishing rod with an attached luminous lure in front of the head. This is the case for the female deep sea angler fish. The body musculature is reduced. In the deeper zones is dominated by macrobenthos. The principle food resources on the deep-sea bottom appear to be the slow fallout of fin and coarse organic detritus from surface waters, the settling of large animal carcasses, the sinking of fecal matter and the transport of organic detritus by turbidity currents. Bacteria are also common in this region. They break down organic matter into simpler inorganic nutrients. [10] The bacteria are consumed by heterotrophic nanoflagellates, which are in turn consumed by ciliates. This food chain is called microbial loop. This loop recycles organic matter that is too small to be consumed by metazoan plankton.

The greater the depth, the more organisms face with increasing physiological stress. One of these stress factors is pressure. Pressure increases by 1 atmosphere for every 10 meters increase in depth. In some areas, oxygen minima layers are present. These oxygen minima are caused by the bacterial breakdown of material sinking from the sea surface. [11]

Threats

Despite the fact that much of the open ocean is remote from the land, it has not escaped human impacts. The main problem is overfishing. To demonstrate this, 90% of stocks of large pelagic fish such as tuna and jacks are removed by fishing. The whole zooplankton communities have shifted their spatial distribution possibly in response to ocean warming. The result of this overfishing is that the fishes of higher trophic levels are replaced by fishes of lower trophic levels. This is called fishing down the marine food web. It is ecologically unsustainable. Another problem is that of pollution. This causes the loss of many species or a degradation of the environment. The introduction of alien species is also a problem. These are species that are introduced in another area and can compete with the indigenous species. This introduction can be done through ballast water from cargo ships or on hulls of vessels.

Legal aspect

In the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS 1982), the definition of the open ocean or High Sea is: ‘The high seas are open to all States, whether coastal or land-locked. Freedom of the high seas is exercised under the conditions laid down by this Convention and the rules of international law. It comprises, inter alia, both for coastal and land-locked States:

- freedom of navigation

- freedom of overflight

- freedom to lay submarine cables and pipelines

- freedom to construct artificial islands and other installations permitted under international law

- freedom of fishing

- freedom of scientific research

The high seas shall be reserved for peaceful purposes. Every State has the right to ships flying its flag on the high seas. Warships on the high seas have complete immunity from the jurisdiction of any State other than the flag State. Ships owned or operated by a State and used only on government non-commercial service shall have complete immunity from the jurisdiction of any State other than the flag State.’ [12]

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|

- ↑ http://www.davidstauffer.com

- ↑

- ↑ Pinet P.R. 1992. Oceanography: An introduction to the Planet Oceanus. West Publishing Company. p. 571

- ↑ http://ocp.ldeo.columbia.edu/climatekidscorner/whale_dir.shtml

- ↑ http://disc.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/oceancolor/scifocus/oceanColor/oceanblue.shtml

- ↑ http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Portuguese_Man-O-War_(Physalia_physalis).jpg

- ↑ http://www.visindavefur.is/svar.php?id=4815

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copepod

- ↑ http://www.lifesci.ucsb.edu/~biolum/organism/photo.html - Steven Haddock

- ↑ Pinet P.R. 1992. Oceanography: An introduction to the Planet Oceanus. West Publishing Company. p. 571

- ↑ Kaiser M. et al. 2005. Marine ecology: Processes, systems and impacts. Oxford University Press. p.584

- ↑ http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/closindx.htm