Sand dune - Country Report, Great Britain

This article on the sand dunes of Great Britain, derives from the 'Sand Dune Inventory of Europe' (Doody 1991) [1]. The 1991 inventory was prepared under the umbrella of the European Union for Dune Conservation [EUDC]. The original inventory was presented to the European Coastal Conservation Conference, held in the Netherlands in November 1991. It attempted to provide a description of the sand dune vegetation, sites and conservation issues throughout Europe including Scandinavia, the Atlantic coast and in the Mediterranean.

An overview article on European sand dunes provides links to the other European country reports. These include chapters from updated individual country reports included as part of a revised 'Sand Dune Inventory of Europe' (Doody ed. 1991) prepared for the International Sand Dune Conference “Changing Perspectives in Coastal Dune Management”, held from the 31st March - 3rd April 2008, in Liverpool, UK (Doody ed. 2008)[2].

Status: This account is based on the revised report for GB with additional information and updated links to site reports.

Contents

[hide]GREAT BRITAIN - Sand Dune Inventory Report

The sand dunes in Great Britain occur extensively around the whole coastline, although sites are fewer in number in the southeast. Sand dunes border only a relatively small proportion of the coastline (7.4%). However, there are approximately 56,000ha of blown sand deposits, including areas afforested or otherwise affected by human use, which have not destroyed the dune landform. Examples exist of all major dune types, including mobile and fixed dunes, machair, dune pasture and dune heath. There are also examples of all the main geomorphological types found in Europe around the British coast.

Surveys of the sand dunes in Great Britain were undertaken in the late 1980s early 1990s. These used standard methods of mapping and vegetation classification in accordance with the National Vegetation Classification (Rodwell 2000). The results were published in three reports: Volume I, England (Radley 1994)[3]; Volume II, Scotland (Dargie 1993)[4]; Volume III, Wales (Dargie 1995)[5]

The surveys were designed to facilitate the selection of sites for conservation designation including Natura 2000, identify ‘Ecological Zones’ and as a basis for monitoring future change. The results highlighted the enormous diversity of coastal sand dune vegetation, with more than 120 distinct types recorded from right across the spectrum of the National Vegetation Classification. They also illustrated the considerable range of variation that exists between different geographical areas. The close relationship between dune vegetation and physical processes was a recurring theme in the reports, as was the influence of changing patterns of land use. The report identified four main issues in coastal dune management for nature conservation. These are:

1. the importance of understanding the role of instability in dune conservation;

2. the need for the management of recreational use;

3. the methods for managing successional change;

4. the importance of naturalness.

The Scottish survey (Dargie 1993), only covered approximately 30% of the resource. It has been extended and a review of all the sand dunes was completed in 1999/2000. Detailed vegetation maps provide national statistics and comparative information between sites and countries.

DISTRIBUTION AND TYPE OF DUNE

The information on the distribution of sand dunes in Great Britain comes from inspection of 1:50,000 Ordnance Survey maps together with additional more detailed survey information where available. This figure also includes areas of coast where wind blown sand forms a veneer over other formations such as shingle deposits and rock outcrops. Typically sand dunes develop above a sandy beach which, when exposed at low water, dries out sufficiently to allow movement of the sand grains by the wind. Specialised plants, notably Ammophila arenaria, trap these particles and help stabilise the shifting substratum. As other plants invade, full successional development takes place when the dune grassland/heathland turns to scrub and ultimately woodland. This latter stage is very rare in Great Britain.

“The Sand Dune Survey of Great Britain (referred to above, 1993-1995) gives the total area of sand dunes as 11,897ha in England and 8,101ha in Wales. The ongoing Sand Dune Vegetation Survey of Scotland indicates that there may be as much as 48,000ha of dune and machair in Scotland, of which 33,000ha is dune. There are approximately 3000 ha of dunes in Northern Ireland. Major dune systems are widely distributed within the UK, being found on all English coasts except the English Channel (other than Sandwich Bay) and the Thames Estuary. They occur on the north and south coasts of Wales and in the northern part of Cardigan Bay. In Scotland dunes are found on all coasts but are less frequent in the North West and in Shetland; they are particularly extensive in the Western Isles and Inner Hebrides where they are associated with machair. In Northern Ireland, the largest dune systems are located along the north and southeast coasts.” Taken from the Joint Nature Conservation Committee web site, sand dune Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP), UK [1].

The dune sites in Great Britain include examples of all the major types found in Western Europe. In the northwest, particularly where the prevailing westerly winds reinforce the dominant winds, large hindshore systems have developed. In the Outer Hebrides, these include some of the best and largest examples of the extensive cultivated sandy plain or ‘machair’ (Ritchie 1979)[6] and (Angus 2001)[7] also present in the west of Ireland. On the east coast where predominant and prevailing winds are in opposition, landward movement is less obvious and spits, barrier islands and bay dunes are more frequent. The majority of dunes have relatively high calcium carbonate content in the dune sand and dune heath occurs in a few scattered locations.

VEGETATION

Sand dunes in Great Britain have a long history of human exploitation, notably for grazing by domestic stock or as rabbit warrens. Consequently, the vegetation becomes grassland or heathland, depending on the original calcium carbonate content of the sand. There is virtually no native woodland and that, which does exist is secondary in nature, resulting from a reduction or removal of grazing animals. The water table can be high and species-rich dune slacks are often present. Destabilisation brought about by recreational use can cause reworking of the sediment to form earlier stages in succession within the main part of the dune. An outline of each of the major plant communities is given below.

Strandline

Typically, this includes species of Atriplex, Cakile maritima and Salsola kali. Examples are scattered around the whole coastline in appropriate locations. In some areas, sandy beaches occur in association with shingle and a number of rare plants may be present including the northern Mertensia maritima or in the south east, Lathyrus japonicus.

Foredune

The dominant dune forming species in Great Britain is Ammophila arenaria, though in the north Leymus arenarius may be equally important. Elytrigia juncea is also a frequent component of the early stages of colonisation particularly where salt spray reaches the upper parts of the beach.

Yellow dune

Although Ammophila arenaria is usually dominant, as the dunes become more stable, there are an increasing number of both annuals and perennials in the vegetation. In the south the local Calystegia soldanella and Eryngium maritimum are often present. Dune grassland. As a more stable form of dune develops, Ammophila arenaria becomes less frequent and under domestic grazing regimes, calcareous grassland is the normal vegetation. Calcareous dune grassland includes by far the most extensive of the plant communities and is present wherever there is a shell sand component in the surface soil. In the south species such as Ophrys apifera, Anacamptis pyramidalis, Blackstonia perfoliata, a variety of grasses (Vulpia membranacea, V. ambigua and Hordeum marinum) and the clovers, Trifolium subterraneum, T, ornithopodioides, T. glomeratum and T. suffocatum, all having important populations. Also important are the machair grasslands of the Outer and Inner Hebrides supporting species typically found much further south.

Calcareous grasslands also occur on cliffs in, especially in northern Scotland where a veneer of sand is blown onto rocky headlands. The sandy grassland (which is perched on the cliff and cliff top) may include Dryas octopetala and Juniperus communis and populations of Primula scotica.

Dune slacks

Dune slacks occur on many dunes and are often rich in species, particularly when associated with calcareous dunes. Here they are often very diverse and include species such as Parnassia palustris, Pyrola rotundifolia and Epipactis palustris. Species also include a number of plants rare in Great Britain such as Liparis loeselii.

Dune heath

Dune heath vegetation develops wherever the sand is free of calcium carbonate, either because of shell fragments, or because of leaching in old established dunes. The dry dune ridges are normally colonised by ericaceous shrubs, notably Calluna vulgaris and Erica cinerea. Northern examples include Juniperus communis and more commonly Empetrum nigrum within dry dune heath. In wetter areas, Erica tetralix is also present. Dunes developed on silica (acid) sands are much less common than those with some shell sand. They occur mostly in northeast Scotland, though isolated examples are scattered at a few locations further south.

Grey dune

Grey dune is differentiated from dune grassland or dune heath, because of the abundance of lichens, which impart a ‘grey’ colour to the vegetation. The communities are often lichen-rich (Rhind et al. 2006)[8] and occur on well-drained, relatively acid soils. These ‘grey dunes’ are often composed of an intricate mosaic of carpet-forming species, including both lichens and mosses such as Cladonia rangiformis, Hypnum cupressiforme, Racomitrium canescens and Syntrichia ruralis ssp. ruraliformis.

Scrub

Most forms of scrub represent retrogressive succession and include Hippophae rhamnoides, which may only be native in southeast England. Elsewhere its introduction to prevent erosion has resulted in it becoming the dominant species on some sites. Woodland. There are no known examples of primary woodland. Betula pendula can form secondary woodland and scrub in the absence of grazing.

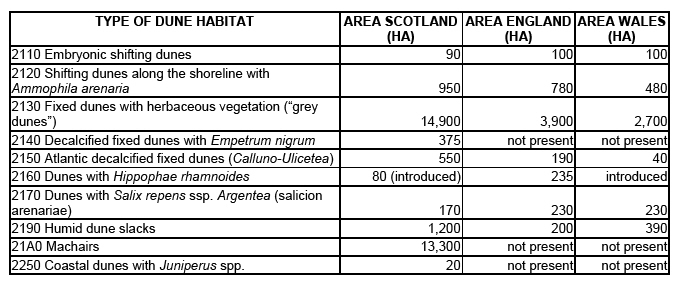

The total area of each of the types of dune vegetation types set out in Annex 1 of the EU Habitats Directive for England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are given in the table below.

Additional data presented for Scotland comes from the most recent dune survey (Dargie 2000)[9] Sand Dune Vegetation Survey of Scotland: National Report, 2 volumes, Scottish Natural Heritage, Battleby, Scotland. Note these figures do not equate directly with those given below in the table listing the sites in Great Britain, as it does not include the data from the additional sites surveyed in Scotland by Dargie (2000).

Data on representation for all UK has been compiled by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) in the Second Report by the United Kingdom under Article 17 of the EC Habitats Directive. JNCC consulted on the draft report in 2007.

IMPORTANT SITES

Sand dunes occur around the coast of Great Britain and include many important sites. Their distribution is shown in a separate article, which includes a map and list of sites.

In the northwest, particularly large hindshore systems have developed examples include a special form, the ‘machair’ present in northwest Scotland and on the west coast of Ireland. Also in the north are the best examples of ‘climbing dune’. These are deposits of sand, blown up and over cliffs to create a sand dune or dune grassland. This grassland may be perched on the cliff and cliff-top and may include mountain avens (Dryas octopetala) and Juniperus communis and populations of Primula scotica. Sites such as Sandwood Bay in the northwest and Invernaver on the north coast of Scotland are especially good examples.

The major sites further south include the Sefton Coast, Newborough Warren, Morfa Harlech and Braunton Burrows (Figure X and the table below). In addition to their size (most are 1,000ha or more in extent) they have rich calcareous grasslands. These also include exceptional examples of wet dune slack with national rarities such as fen orchid (Liparis loeselii).

On the east coast where predominant and prevailing winds are in opposition, landward movement is less obvious and spits, barrier islands and bay dunes are more frequent. The most important are those associated with the complex shingle barrier islands saltmarshes and dunes of north Norfolk.

The majority of dunes have relatively high calcium carbonate content in the dune sand and as a result, dune heath occurs only in a few scattered locations. They are found mostly in northeast Scotland, though isolated examples are present elsewhere around Great Britain. The dunes of the Morrich More in the northeast are perhaps the most important example. This site has extensive Calluna vulgaris heath with Juniperus communis a major and conspicuous component of the vegetation. The site is enhanced by some of the most complete transitions from upper saltmarsh to dune vegetation in Britain. The Sands of Forvie in Scotland, Winterton dunes in Eastern England and Studland on the south coast are the three other significant examples and are all protected as National Nature Reserves.

There are approximately 120 sites identified as Sites of Special Scientific Interest protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. The sites listed in the table below and shown in the figure are all over 50ha, and considered to be of national importance as examples of dune habitat. The code number provides a link to the description of the Special Area of Conservation (SAC) designated under the European Union Habitats Directive and held on the Joint Nature Conservation Committee Web Site.

Table of sites to be inserted here.

NNR, National Nature Reserve; NT, National Trust land; LNR, Local Authority Reserve and PR, Private nature reserve. Forest in “other habitats” indicates substantial areas planted with conifers.

CONSERVATION

Historically humans have exploited dunes in Great Britain in a variety of ways. They are particularly vulnerable to development and building of houses, airfields, car parks and caravan sites and the development of golf courses have all taken their toll. The planting of artificial forest composed of non-native pines not only destroys the natural dune vegetation as the canopy closes, but also can result in an adverse change in the dune hydrology which may influence the vegetation at some distance from the forest. Sand extraction and recreational activities are also important and attempts to stabilise the sand movement are commonplace. However much more important in the long term is the over-stabilisation of the dune and its vegetation in the absence of grazing either by domestic stock or rabbits. See Rhind et al. (2007)[10]for a description of the situation in Wales.

Sand dunes are inherently unstable and cycles of erosion and stabilisation are extremely important to the survival of their plant and animal life. There appears to be a worldwide decrease in sediment availability along coastlines and this is particularly marked in the case of sandy beaches (Bird 1984)[11]. Evidence from Ireland suggests that the main dune-building phase finished around 2,500 BP and that few dune systems are actively accreting today (Carter 1988)[12]. This is also true for the rest of the British Isles where, with notable exceptions such as Tentsmuir Point in Fife, Morfa Harlech in Gwynedd and Tywyn Point in South Wales where local progradation is taking place, most other dune systems are fossilized and/or actively retreating landwards.

Human use

Humans, as far back as Neolithic times have exploited sand dunes. A great variety of activities, including recreation and recreational development, afforestation, agriculture and the siting of airfields, housing and industry, replaced traditional management practices such as grazing over the last 50 years or so. All of these uses have led to a decrease in natural and semi-natural dune habitats. The following paragraphs provide an indication of these losses:

Afforestation

Afforestation, often used to stabilise mobile dunes affects nearly 8,000ha, or approximately 14% of the total dune area of Great Britain. Almost total destruction of the native flora and fauna occurs within a very few years, especially when sand dunes are planted with alien conifers. The progressive shading of the vegetation and the deposition of a carpet of inert needles bring this about. Although initial attempts at dune afforestation occurred before the twentieth century, the first widespread planting occurred between 1922 and 1952 when 4,000ha of dune were afforested (Macdonald 1954)[13]. For details of the scale and impact of the loss of sand dune habitat in Great Britain, see Doody (1989)[14].

Agriculture

Historically the most common use of dunes has been grazing by domestic stock. On calcareous systems, this has helped to create a rich flora and fauna similar to that of inland calcareous grasslands. Whilst continued grazing is necessary for the survival of the rich plant communities, overgrazing on calcareous dunes by cattle, sheep, particularly when combined with burrowing rabbits can lead to unstable conditions and eventually, large-scale erosion. Agricultural intensification has also destroyed many of the oldest most stable parts of the major dune systems in Great Britain. These areas lie under arable fields or permanent pastures.

Heathland vegetation that develops on acid dunes is vulnerable to grazing and even quite low levels may cause loss of vegetation and its replacement with species poor grassland. In contrast to the over-exploitation of dunes for agriculture, problems may also arise because of too little management (Doody 1989)[15]. Calcareous dune systems require a certain level of grazing to ensure the retention of species-rich communities. At many sites where grazing management has ceased in recent years, the growth of coarse grasses followed by scrub invasion threatens the survival of plant and animal communities. This is particularly noticeable where part of the dune has been afforested or where other invasive species such as Hippophae rhamnoides or rhododendron have been introduced

Recreation

Recreational use of dunes is an important factor helping to cause instability. Activities come in a variety of forms and include trampling, lighting fires, excavating sun-traps, pony riding, vehicular traffic and in the higher dune ridges ‘sand sliding’. The impact of these activities varies with their scale and the intensity of use. Inevitably as trampling or other use intensifies then the destruction of the surface vegetation follows, exposing the underlying sand to the action of wind and rain. This in turn may make the dunes mobile again causing sand to invade agricultural land and/or housing and other infrastructure.

Clearly, in the situation described above, wholesale destruction of the vegetation occurs, requires remedial action. Stable and species-rich vegetation can recover from prolonged trampling and subsequent shifting dunes, with the removal of the damaging activities. Restoration work can rehabilitate dune vegetation, although it is often not possible to re-establish the original vegetation in the short term. Planting Marram grass, to re-create semi-stable foredunes, given time can develop into stable dune grassland. However, severe erosion is often very localised and whilst dune managers concern themselves with stabilisation, in the absence of grazing, adjacent areas may become stable with an equally important loss of open dune vegetation as scrub develops. Sand dunes make ideal places for golf course development. In fact some of the most important golfing venues are on ‘links’ courses and there are many that have been developed on sand dunes in Great Britain. The extent of loss of the dune flora and fauna varies on different courses but destruction of the semi-natural vegetation occurs in areas converted to greens, tees and fairways. All golf courses contain areas of ‘rough’ and intensive management restricts the richness of the vegetation. By contrast on a few sites relatively large and intact areas of ‘rough’ remain, which support important plant and animal communities. In these areas, management intensity is low, perhaps involving mowing on an annual cycle or grazing at low levels.

Military use

Military use of dunes has a rather paradoxical position in the recent history of dune conservation. It seems clear that during the Second World War, training activities caused disturbance and when combined with high rabbit numbers caused the destruction of large areas of vegetation and exposure of sand. At Braunton Burrows (Devon, England), for example some there was a loss of 100ha vegetation. Replanting with Ammophila arenaria and myxomatosis, which decimated the rabbit population helped stabilise the system. Military use has also protected a number of dunes from the worst effects of agricultural intensification and afforestation. Amongst these, the most significant is Morrich More in Ross and Cromarty District, Scotland, although Torrs Warren (Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland) and Tywyn Gwendraeth (West Glamorgan, Wales) are of national importance and included within the GB Natura 2000 series. The direct impact of the vegetation is limited to the area immediately near the targets, which are themselves widely separated. In each case their use (mainly for bombing practice) has created relatively little widespread disturbance of the natural vegetation.

Other development

Airfields (both military and civilian) have also had an impact on dune vegetation. Road and railway lines affect many dune systems and housing and other buildings, including permanent caravan parks, have taken their toll. The development of the last of these can increase problems of erosion caused by trampling feet as mentioned above.

General issues

Sand dunes have important successional characteristics, which if left to develop naturally would result, on the larger systems at least, in a complete transition from accreting foredune to woodland. Destruction of the older, landward sections of the sand dunes occur first. As a consequence there are only very limited examples of sand dunes where the whole system remains intact. The remaining areas of dunes represent truncated successions.

Sand dunes provide ideal conditions for the invasion of alien plants, because of their open and often unstable nature. Of the 900 vascular plants found on sand dunes in Great Britain only 400 or so are truly native (Ranwell 1972)[16]. Hippophae rhamnoides is a species native to the south and east of England. Today it occurs throughout much of Great Britain except the north of Scotland. Its introduction has helped to protect vulnerable, unstable dunes. However, it has expanded rapidly and in many sites, this has been at the expense of semi-natural dune grassland. The plant’s ability, once established, to grow vegetatively and produce a closed canopy has eliminated most of the native dune plants and animals. Eradication is difficult and requires constant treatment.

Additional information

Ecosystems of the World 2A Dry Coastal Ecosystems, Polar regions and Europe (Boorman 1993) [17]

Other information on spiders (Duffey 1968)[18].

WEB SITES and other survey information

It is now possible to identify the location of sand dunes and their nature conservation designation via the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs web site [2]. The MAGIC map-based tool includes a Coastal Resource Atlas. It can generate maps to a high level of detail and it is possible to download them in GIF format.

The Joint Nature Conservation Committee also has a complete list of all the designated sites in the United Kingdom. Individual sites accessible via a map [3] or from a list [4].

General: The sand dune and shingle network hosted by Liverpool Hope University [5]. The Coastal Dune and Shingle Network promotes a ‘habitat based’ and ‘evidence informed’ approach to the solution of management issues for these two habitats.

General issues - restoration: The results of a LIFE project “LIFE Co-op: bogs and dunes - The PROMME decision-tree” include a decision support tree for sand dune restoration. This is accessible [6]

Cornwall sand dunes, south west England, UK. The County Council has worked for decades to improve the management of Cornwall's sand dunes and has produced a comprehensive guide for exploring the sand dunes in Cornwall. [7]

Wirral, northwest England, UK. The sand dune habitats in Wirral cover approximately 80ha. (approx. 0.15 % of UK area) this represents all of Cheshire’s sand dune resource. See: [8]

Sands of Time, This site provides information on the sand dunes of the Sefton Coast, north west England - how the coast has changed in the past, what is happening today and some possible future conditions. [9]

Sefton Coast Partnership, north west England, UK. [10]

References

- Jump up ↑ Doody, J.P., ed., 1991. Sand Dune Inventory of Europe. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee/European Union for Coastal Conservation.

- Jump up ↑ Doody, J.P., 2008. Sand Dune Inventory of Europe, 2nd Edition. National Coastal Consultants and EUCC - The Coastal Union, in association with the IGU Coastal Commission.

- Jump up ↑ Radley, G.P., 1994. Sand dune vegetation survey of Great Britain. Part 1 - England. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Jump up ↑ Dargie, T.C.D., 1993. Sand dune vegetation survey of Great Britain. Part 2 - Scotland. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Jump up ↑ Dargie, T.C.D., 1995. Sand dune vegetation survey of Wales. Part 3 - Wales. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

- Jump up ↑ Ritchie, W., 1979. Machair development and chronology in the Uists and adjacent islands. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 77B, 107-122.

- Jump up ↑ Angus, S., 2001. Moor and Machair. The Outer Hebrides. White Horse Press, Cambridge.

- Jump up ↑ Rhind, P., Stevens, D. & Sanderson, R., 2006. A review and floristic analysis of lichen-rich grey dune vegetation in Britain. Biology and Environment: Proceedings of the Royal Academy, 106B/3, 301-310.

- Jump up ↑ Dargie, T.C.D., 2000. Sand Dune Vegetation Survey of Scotland: National Report. 2 volumes, Scottish Natural Heritage, Battleby.

- Jump up ↑ Rhind, P., Jones,, R. & Jones, L., 2007. Confronting the impact of dune stabilization and soil development on the conservation status of sand dune systems in Wales. ICCD.

- Jump up ↑ Bird, E.C.F., 1984. Coasts - an Introduction to Coastal Geomorphology. 3rd Edition, Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

- Jump up ↑ Carter, R.W.G., 1988. Coastal Environments. An Introduction to the Physical, Ecological and Cultural Systems of Coastlines. Academic Press, London.

- Jump up ↑ Macdonald, J., 1954. Afforestation of sand dunes. Advancement of Science, 11, 33-37.

- Jump up ↑ Doody, J.P., 1989. Conservation and development of coastal sand dunes in Great Britain. In, Perspectives in Coastal Dune Management, ed., F. van der Meulen, P.D. Jungerius & J. Visser, pp. 53-67. The Hague: SPB Academic Publishing.

- Jump up ↑ Doody, J.P., 1989. Management for nature conservation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 96B, 247-265.

- Jump up ↑ Ranwell, D.S., 1972. Ecology of Salt Marshes and Sand Dunes. London, Chapman and Hall, 258 pp.

- Jump up ↑ Boorman, L.A., 1993. Dry coastal ecosystems of Britain: dunes and shingle beaches. In: Ecosystems of the World 2A Dry Coastal Ecosystems, Polar regions and Europe, ed., van der Maarel, Elsivier, 199-218.

- Jump up ↑ Duffey, E. 1968. An ecological analysis of the spider fauna of sand dunes. Journal of Animal Ecology, 37, 641-674.

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|