History of Belgian sea fisheries

Contents

Introduction

| The early period (15th - 17th century) | |

|---|---|

| 1163 | Founding of the city of Nieuwpoort: ’Keure van Nieuwpoort’ (with, among others, tax rate for herring, cod, plaice,...) |

| ca. 1396 | Gilles Beukels and Jacob Kiel invented the technique for the concervation of herring: 'kaken' |

| 15th – 16th century | flowering period for the Flemish herring fisheries |

| 1475 | Start Flemish ‘doggevaert’ (cod fishery) on the ‘Doggerbank‘ |

| 16th – 17th century | political turmoil causes the decay of Flemish fisheries |

| andere titel dan gouden periode (1700-1830) | |

| 1722 | foundation of the Oostendse Compagnie for the revival of Flemish fisheries and trade with China and Bengal (until 1731) |

| 1792-1815 | incentives for herring- and cod fishery |

| 1815 | Willem I of the Netherlands: new fisheries legislation |

| 1820 | the 'piscina' or 'beun' (a tank filled with sea water that kept the fish alive) is used for the first time on trawlers of Oostende |

| 1822 | first 'trawl vessel' makes its entrance in Flemish fisheries (Oostende) |

| Early Belgian period (1830 - 1914) | |

| 1832-1842 | Belgian premium system is a fact |

| 1867 | abolition of the premium system |

| 1874 | use of ice to keep the fish fresh on board finds entrance |

| 1881-1885 | Belgium defends the "inexaustibility of the sea" (following the British ideas): 'fishing can continue indefinitely' |

| 1884 | launching of the first steam trawler in Oostende |

| 1894 | Intrance of the 'otter trawl' in Belgium, a fishing method less damaging for the seabed than beam trawling |

| 1898 | flowering of the steam fishery and revival of sea fisheries |

| 1903 | Belgium officially joins the International Council for Exploration of the Sea (ICES), which deals, among other things, with the overfishing problems |

| 1905 | steam trawlers of Oostende go, for the first time, to Spain and Portugal and later also to the White Sea |

| 1907 | first time auxiliary engines are used on sail boats in the Belgian fishery |

| Great revolution (1914 - 1950) | |

| 1912 | foundation of the Provincial Fisheries Commission of West-Flanders |

| 1914 – 1918 | Belgian sea fisheries are almost completely interrupted by World War I |

| 1914 – 1918 | sea fisheries in Oostende during WWI |

| 1914 | the use of natural ice is completely supplanted by artificial ice |

| 1915 | during WWI, the German occupier allows restricted fishing during the day |

| 1919 – 1930 | flowering of steam fisheries, big upswing for motor fisheries and full decline of sail fisheries |

| 1928 | procurement of the new fish market in Oostende |

| 1932 | Belgian sea fisheries experience a big crisis, mainly by leaving the 'golden standard' in Great-Britain |

| 1937 | first International Convention concerning overfishing signed by 10 EU counties in London |

| 1940 – 1945 | Belgian sea fisheries during WWII: big landings of herring |

| Industrial fisheries (1950 - 2000) | |

| 1958 | extension of the Icelandic territorial waters and thus fishing limits to 12 sea miles: first cod war |

| 1963 | sailing vessels (ca 1930) and steam vessels are permanently displaced by the big emergence of motorized vessels |

| 1983 | Common Fisheries Policy of the European Union becomes operative: a tool for the management of fishery and aquaculture |

| 1995 | UN Fish Stocks Agreement: defines obligations and responsibilities for state members regarding fishery and focuses on illegal fishing |

As from the early Middle-Ages, the ports of Oostende and Nieuwpoort enjoyed a certain prosperity and status in the field of fisheries and trade. This period (15th – 17th century) is also known as the 'Golden age'[1] of the Flemish sea fisheries. Especially the salted herring[2]-, and later the salted cod fishing[3], was important. Yet, sea fisheries also knew hardship. Political turmoil, during which Oostende and Nieuwpoort were alternately under siege, would (during the 2nd half of the 16th century) ultimately lead the fisheries into decay[4] for a long period of time.

The Austrian reign (1713-1794) brought a revival in the Flemish sea fisheries, but this was only temporary: during the French Republic (1795-1804) and the French Empire (1804-1814), there was another decline. When William I of the Netherlands took control in 1815, he wanted to boost the fishing-industry with a new fisheries policy and grants. This caused great displeasure: the Flemish fishermen did not agree[5] with the meddling of the Dutch government. Moreover, according to the Flemish ship-owners, this system of state subsidies was not adapted to the specific nature of the Flemish sea fisheries.

The independence of Belgium in 1830 entailed an adapted system of state subsidies, which soon doubled the number of ships and gave a boost to employment in the sector. Between 1832 and 1864, the total number of vessels increased from 145 to 274 as a direct effect[6] of the system of subsidies. Ten years after the independence, cod landings in Oostende had already tripled. The herring catches also did well. The system of subsidies was soon to be questioned internationally, because of its great impact on government budgets. A National Commission of inquiry on sea fisheries[7] was established, and the first fisheries statistics were collected. After the United Kingdom, and later the Netherlands, let go of the system of subsidies, it was also abolished[8] in Belgium in 1867.

Important developments in technology (e.g. (steam) engines[9] and the use of artificial ice[10]) revived the fisheries at the end of the 19th century. Thanks to this progress, more distant waters could be exploited and bigger catches could be landed. The was a strong belief in an ‘inexhaustible sea’.

Despite the undeniable impact of WWI[11], fisheries recovered fairly quickly. With the warfare came technological innovations (such as diesel engines and sonar) that could be applied for boosting the fisheries. During WWII[12], the North Sea was almost free of fishing activity because of the threat of war. This allowed the fish stocks to grow strongly. An important part of the fleet fled abroad, in particular to England. The part of the Belgian fleet that stayed in their home ports was exceptionally allowed to fish in coastal waters from 1941 onwards and landed record amounts of herring[13].

After the war, the industry was centered in the ports of Zeebrugge and Oostende, and in a lesser amount in Nieuwpoort and Blankenberge, and had increased investments in infrastructure and technology. Once again, the sector could count on state support to repair the damage the war had done. With the return of the exiled fishermen new knowledge was brought in the sector.

Shortly after the war, a historical record of 75,370 tonnes of fish was landed by Belgian fishermen (1947).

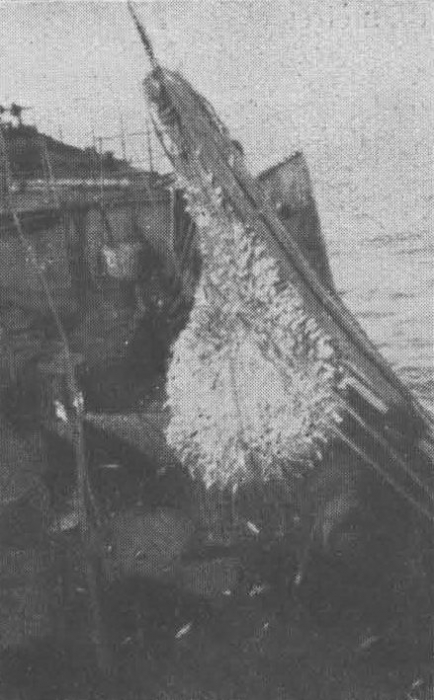

Because of the over-exploitation of herring and sprat and the economic crisis at the end of the 1940s, Belgian fishermen turned towards the rich cod fishing areas in Iceland. When the ‘Cod wars’[14] (1958-1961 and 1972-1975) expelled the British and German fleets from the Icelandic waters, the Belgians were granted an exception to keep fishing for gadoids[15]. From the 1980s onwards, flatfish fisheries became more important. The introduction of adjustments in the ‘beam-trawl’ (link foto1, foto2), a gear which was already used in the shrimp fishery, was the key to success. Sole and plaice were the most important target species for this fuel-intensive bottom trawl fisheries. Due to the large bycatches and impact on the seabed, this fishing technique was increasingly questioned.

Sustainable fishery

Today, sole and plaice are still the main target species of the Flemish sea fisheries, which makes them vulnerable. The profitability of the fishery sector is also under pressure. The greatly reduced fleet furthermore struggles with a desperate shortage of young fishermen. Another problem is the aging of the fleet.

But not all hope seems lost: a global action- and restructuration plan[16] proposes measures to obtain sustainable Flemish sea fisheries[17]. Moreover, the European Common Fisheries Policy[18] slowly provides for more diversity in the catches, among other things, by means of the landing obligation[19].

Important species

During the 20th century, the Belgian fisheries overall showed three successive exploitation phases. One could say there was a ‘herring-period’ (until 1950), a ‘cod-period’ (1950 – 1980) and a ‘flatfish-period’ (after 1980). A similar pattern[20] was described for the fisheries exploitation phases worldwide. Between 1930 and 2000, a handful of fish species explain for about 75% of the total landings. These were mainly herring (and sprat as well), cod (and other round-fish species) and the flatfish species plaice and sole. From 2000 onwards, the relative importance of these species in the total landings decreased. Lately there is an increasing supply of anglerfish, cuttlefish and scallops.[21]

Important fishing areas

The successive exploitation of target species was related to fishery in specific fishing grounds: beginning with the coastal waters for herring, followed by the Icelandic Sea for cod, the Southern and Central North Sea for sole and plaice, and later by extension also the Western waters for flatfish fishery. The nearby fishing grounds (Belgian coastal waters, Southern North Sea, West- and East-coasts of Central North Sea) and more distant areas such as the Northern North Sea and the Western waters (Bristol Channel and English Channel, South- and West-Ireland) were, over the entire period covered by the official fisheries statistics[22], important for Belgian fisheries.

From the beginning of 20th century until the start of WWI, the landing originated mostly from the North Sea. The yearly supplies fluctuated between 10,000 and 15,000 tonnes.

After WWI, the landings quickly recovered to the pre-war level[6]. In the period of 1920-1926 the landings originated mainly from fishing grounds of the Southern North Sea, including the coastal waters. From 1928 onwards, the importance of the nearby fishing areas decreased and between 1934 and 1939, the main fishing grounds were alternately located in Iceland and the Western waters (West-Scotland, South- and West-Ireland, the Bristol Channel). At the outbreak of WWI, fishing was only allowed in the coastal waters, which (along with sprat) produced unprecedented amounts of herring. By the end of WWII, 10% of the landings originated from the Southern North Sea, but after the war the fishermen soon returned to the Western waters. Between 1950 and 1970 the increase in landings from the Icelandic Sea was the most notable trend[14]. The activities in the Icelandic waters that started in the 16th century, ceased completely in 1995[23]. From 1982 onwards, the fishery management is mainly determined by the European Common Fisheries Policy[18], which imposes quota and other restrictions in fleet size and fishing effort.

Belgian fishing ports

Up until 1911, Oostende was the most important port, mostly because it was more suited for receiving large ships. From the end of the 19th century onwards, Oostende focused more on fishing during winter, especially since steam trawlers arrived in 1884. The facilities of the new port of Zeebrugge were inaugurated in 1907. The fishery port of Nieuwpoort, the settlements of Heist and Blankenberge to the east, and de Panne/Adinkerke and Oostende/Koksijde to the west, harboured an important amount of vessels as well at that time.

After WWII, fishery became a matter for larger companies. Fisheries were mainly centered in the ports of Oostende, Zeebrugge and Nieuwpoort and, like the ports along the estuary of the river Scheldtsmaller moorings (De Panne, Koksijde,...) gradually disappeared.

Paired beam-trawl fishery (picture) (pulling a beam-trawl on each side of the vessel) was carried out from the port of Zeebrugge. This technique was originally used for shrimp fisheries since the end of the 1950s, but it was also deployed for the fishing of sole and plaice from the 1960s onwards. From Zeebrugge, there were also successful ventures for ‘twin trawling’ (picture) (where two ships pull one otter trawl) for the fishing of cod, which increased the relative importance of the port of Zeebrugge port. Although Zeebrugge has taken the lead in terms of annual landings in Belgian ports since 1985, Oostende remains the most important port when it comes to the global landings in Belgian ports over the past century: 68% of the reported landings were auctioned in Oostende, versus 24% in Zeebrugge, 8% in Nieuwpoort and less than 1% in Blankenberge. Oostendes downturn as the main port is, among other things, related to the disappearance of the large steam trawlers after WWII and the gradual loss of the traditional and distant fishing grounds (like the Icelandic waters).

References

- ↑ Degryse, R. (1944), Vlaanderens haringbedrijf in de Middeleeuwen. De Seizoenen, 49. De Nederlandsche Boekhandel: Antwerpen. 116 pp

- ↑ Debergh, H.; Lescrauwaet, A.K.; Scholaert, A.; Mees, J. (2011),Haring - Clupea harengus. Een eeuw zeevisserij in België. VLIZ Information Sheets, 295. Vlaams Instituut voor de Zee (VLIZ): Oostende. 14 pp.

- ↑ Lescrauwaet, A.-K.; Debergh, H.; Scholaert, A.; Mees, J. (2011), Atlantische kabeljauw - Gadus morhua. Een eeuw zeevisserij in België. VLIZ Information Sheets, 215. Vlaams Instituut voor de Zee (VLIZ): Oostende. 12 pp.

- ↑ Hovart, P. (1985), Zeevisserijbeheer in vroegere eeuwen: een analyse van normatieve bronnen. Mededelingen van het Rijksstation voor Zeevisserij (CLO Gent), 206. Rijksstation voor Zeevisserij: Oostende. III, 192, VII pp.

- ↑ (1817), Mémoire présenté au roi sur la pêche nationale. West-Flandre 1817. Imprimerie de P. Scheldewaert: Ostende. 57 pp.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 De Zuttere, C. (1909), Enquête sur la pêche maritime en Belgique: introduction, recencement de la pêche maritime. Lebègue & cie: Bruxelles. 634 pp.

- ↑ (1866), Rapport de la Commission chargée de faire une enquête sur la situation de la pêche maritime en Belgique. Séance du 17 mai 1866. Chambre des Représentants: Bruxelles. XLII, 75 pp.

- ↑ Hovart, P. (1994), 150 jaar zeevisserijbeheer 1830-1980: een analyse van normatieve bronnen. Mededelingen van het Rijksstation voor Zeevisserij (CLO Gent), 235. Rijksstation voor Zeevisserij: Oostende. 317 pp.

- ↑ Vroome, E. (1957), De evolutie van de Oostendse vissershaven: een duizendjarige reuzenstrijd. Emile Vroome: Oostende. 48 pp.

- ↑ Poppe, M. (1977), Van mannen en de zee: een eeuw Vlaamse zeevisserij 1875-1975. Nieuwsblad van de Kust: Oostende. 60 pp.

- ↑ Demasure, B. (2013), Visserij en de Eerste Wereldoorlog ’Den oarienk eeft uus gered’, in: De Grote Rede 36: De Groote Oorlog en de Zee. De Grote Rede: Nieuws over onze Kust en Zee, 36: pp. 90-96

- ↑ De Mulder, A. (1984), Belgische zeevisserij onder de bezetting 1940-1945. Sirene 35(136): 12-14

- ↑ Lescrauwaet, A.-K.; De Raedemaecker, F.; Vincx, M.; Mees, J. (2013), Flooded by herring: Downs herring fisheries in the southern North Sea during World War II, in: Lescrauwaet, A.-K. Belgian fisheries: ten decades, seven seas, forty species: Historical time-series to reconstruct landings, catches, fleet and fishing areas from 1900. pp. 164-181

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Omey, E. (1982), De zeevisserij: een struktuuranalyse van de Belgische zeevisserij. Reeks van het Westvlaams Ekonomisch Studiebureau, 27. Westvlaams Ekonomisch Studiebureau: Brugge. 256 pp.

- ↑ Depotter, J. (2011), Onze Ijslandvaarders: Deel 1. Academia Press: Eekhout. ISBN 978--90-382-1873-1. XVI, 552 pp.

- ↑ Adriaens, P.; Vanagt, T.; Couderé, K. (2013), Strategische Milieubeoordeling van het Belgisch Operationeel Programma voor de Belgische visserijsector, 2014-2020. Technum: Antwerpen. 207 pp.

- ↑ De Snijder, N.; Brouckaert, E.; Hansen, K.; Heyman, J.; Polet, H.; Welvaert, M. (2015), Vistraject: Duurzaamheidstraject voor de Belgische visserijsector . ILVO/Rederscentrale: Oostende. 131 pp.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Verleye, T.J.; Pirlet, H.; Lescrauwaet, A.-K.; Maes, F.; Mees, J. (Ed.) (2015), Vademecum: Mariene beleidsinstrumenten en wetgeving voor het Belgisch deel van de Noordzee. Vlaams Instituut voor de Zee (VLIZ): Oostende. ISBN 978-94-920431-6-0. 128 pp.

- ↑ Polet, H.; Torreele, E.; Pirlet, H.; Verleye, T. (2015), Visserij, in: Pirlet, H. et al. (Ed.) Compendium voor Kust en Zee 2015: Een geïntegreerd kennisdocument over de socio-economische, ecologische en institutionele aspecten van de kust en zee in Vlaanderen en België. pp. 141-156

- ↑ Pauly, D.; Watson, R.; Alder, J. (2005), Global trends in world fisheries: impacts on marine ecosystems and food security. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. (B Biol. Sci.) 360(1453): 5-12. hdl.handle.net/10.1098/rstb.2004.1574

- ↑ Tessens, E.; Velghe, M. (2015), De Belgische zeevisserij 2014: Aanvoer en besomming: Vloot, quota, vangsten, visserijmethoden en activiteit. Departement Landbouw en Visserij: Brussel. 116 pp.

- ↑ Lescrauwaet, A.-K.; Debergh, H.; De Hauwere, N.; Vanhoorne, B.; Lyssens, L. (2009), Een eeuw zeevisserij in België: Handleiding bij de standaardisering en geografische afbakening van de historische visgronden (1929-1999) in de Belgische zeevisserijstatistieken. VLIZ Information Sheets, 249. Vlaams Instituut voor de Zee (VLIZ): Oostende. 14 pp.

- ↑ Lescrauwaet, A.-K.; Vincx, M.; Vanaverbeke, J.; Mees, J. (2013), 'In Cod we trust': Trends in gadoid fisheries in Iceland 1929-1996, in: Lescrauwaet, A.-K. Belgian fisheries: ten decades, seven seas, forty species: Historical time-series to reconstruct landings, catches, fleet and fishing areas from 1900. pp. 182-197