Fishing past and present: Belgium

Fishing past and present: Belgium

Contents

Reconstructed time-series and results for Inshore fisheries

Fleet

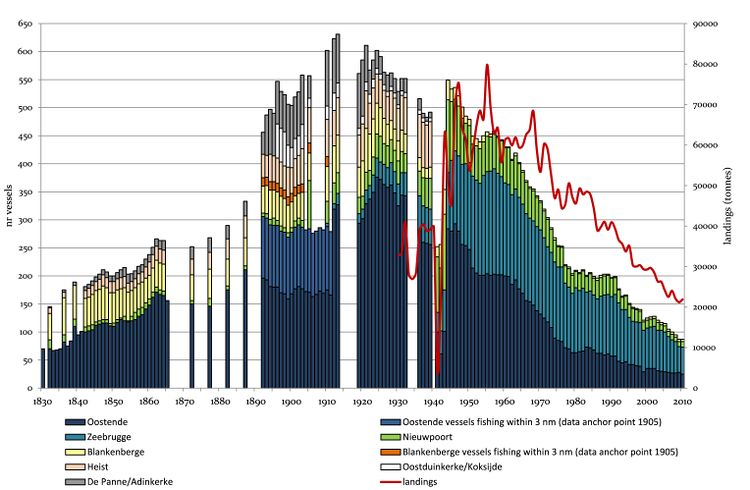

The data integration covers the period from 1830 to 2010. In spite of the data gaps (1865-1871 and 1915-1918, see Annex B) the time-series reconstructs the overall trend in total number of fishing vessels. From the beginning of reporting, the total number of vessels increased from 145 in 1832 to 274 in 1864, nearly duplicating in 3 decades (Figure 3). This increase is explained as a direct effect of the system of subsidies (De Zuttere 1909). Oostende remained the most important port throughout this period and the next period of reporting (1892-1911.), as it was more apt to receive larger vessels. The facilities of the new port of Zeebrugge were inaugurated in 1907. The fishing port of Nieuwpoort, the settlements of Heist and Blankenberge to the east, and De Panne/Adinkerke and Oostduinkerke/Koksijde to the west also harboured an important number of vessels. Most of these vessels were inshore vessels that stranded on the beaches to disembark the produce, or used the neighbouring ports of Nieuwpoort, Blankenberge and later Zeebrugge to do so. By the end of the 19th century, Oostende increasingly focused on ‘fresh fish’ catches during winter, in particular with the appearance of steam trawlers from 1884-1887 onwards. De Panne/Adinkerke, Oostduinkerke/Koksijde, Heist and Blankenberge were home to vessels of coastal fisheries and fishing areas at shorter distances.

A maximum total number of 630 fishing vessels was reported in 1913 (Commissie voor Zeevisscherij 1913), at the outbreak of the First World War (WWI, 1914-1918). At the eve of WWI, the new port infrastructure of Zeebrugge was harbour to 20 sailing vessels, Oostende to 327 of which 29 steamers, followed by De Panne (87), Heist (67), Blankenberge (67), Nieuwpoort (37) and Oostduinkerke/Koksijde (26). While the fleet size quickly recovered from the destruction suffered during WWI, a revolution took place in fishing power of the fleet as they moved from sail or steam as driving power, to motor engines during the inter-war period (1919-1939). Motors were first installed as donkeys (to lift the nets) and as auxiliary power (propelling power) on sailing vessels and progressively as central driving power (Commissie voor Zeevisscherij 1912, 1913, 1919-1931).

These shifts also required considerable investments and after WWII, fishing moved from a more family-oriented business to shipping companies. Fishing activities became concentrated around only 4 (Oostende, Zeebrugge, Nieuwpoort, Blankenberge) of the previously mentioned ports or fishing communities.

The sector was severely hit by an economic crisis in 1948 and in only 10 years’ time, the fleet size decreased from approximately 550 to 450 vessels (-20%). The larger otter trawling vessels were forced to shift their fishing activities to the Icelandic waters to ensure profitability. By 1958, the landings from the Icelandic Sea represented 40% of all fish disembarked by Belgian fishermen (Lescrauwaet et al. 2010a). Another segment of the fleet targeted the rich concentrations of flatfish (mainly sole) on the White Bank (eastern part of the central North Sea). When the catches of sole decreased on the White Bank after 1955 the Belgian fisheries returned to the western fishing grounds (South-West Ireland, Bristol Channel), which they had left 10 years before in favour of the North Sea.

Figure: Trend in number of vessels of the Belgian fishing fleet in the period 1830-2010. Source: VLIZ HIFIDatabase, reconstructed from historical sources Annex B

In the 1960s, major structural changes took place in the Belgian sea fisheries fleet. The large shipping companies which had invested in steam trawlers disappeared (e.g. the Ostend Shipping Company): the last Belgian steam trawler sailed out to England on the 14th of January 1964 exactly eighty years after the first steam trawler entered in the port of Oostende. Between 1961 and 1969, governmental subsidies were issued for the renewal of the fleet with bounties for the demolition of older ships and for the purchase of new steel hulled medium-sized motor trawlers (Poppe 1977). Although the beam-trawl was introduced in 1822 in Oostende, it went nearly unnoticed until the 1960s. In 1959, the paired beam-trawl fishery (‘bokkenvisserij’, a ship pulling one beam-trawl on each side of the vessel) was implemented from the port of Zeebrugge: first for the brown shrimp (Crangon crangon) fisheries that typically take place in inshore waters, and later also for the sole fisheries. Also from Zeebrugge, succesful ventures for pair-otter trawl (‘spanvisserij’, two ships pulling one otter trawl) fisheries for cod were implemented which increased the relative importance of Zeebrugge as fishing port. Whereas the port of Oostende had kept its reputation of first fishing port since at least the 18th century (Cloquet 1842, De Zuttere 1909) Zeebrugge definitely took over in 1968 as the most important port in terms of fleet size and in 1985 in terms of landings.

Landings

Trends in landings per unit of effort in Belgian Inshore waters

Since the Middle Ages, Flemish fisheries have targeted a variety of fishing grounds, many of which were distant fishing areas. Still, in spite of its limited extension, the Belgian part of the North Sea BNS has been historically the most important fishing area for Belgian fisheries, representing over 20% of the total Belgian landings (Lescrauwaet et al. 2010a). The waters of the BNS are considered as the most important fishing area in terms of source of food for local population, but also as the most stable provider of food. The BNS and in particular the ecosystem of shallow underwater sandbanks is also important as (post)spawning and nursery area (Leloup and Gilis 1961, Gilis 1961, Leloup and Gilis 1965, Rabaut et al. 2007). Recent studies also suggest that since the 2000s, approximately 50% of all Belgian removals from the BNS are unreported landings and discards (IUU) and total fish discarded by the Belgian fisheries on the BNS may range between 30-40% of all Belgian landings from the BNS. These numbers do not take into account the non-commercial benthic species (e.g. crab, algae) and the catches by the French and Dutch fleets that also have a long-standing tradition of fishing in the BNS (Depestele et al. 2011). Commercial catch per unit of effort (CPUE) - and its variant LPUE - is widely used as an index of abundance of fish, although the factors that may potentially bias this index are well documented and the index may be less suitable for pelagic species that display schooling behaviour (Hilborn and Walters 1992). The index needs to be used for specific métiers and particular fishing areas, in order to be interpreted as a relative index of abundance. This analysis is conducted for the demersal fisheries in the BNS, targeting mainly flatfish. Similar as for the overall Belgian sea fisheries, the time-series for LPUE of the demersal (flatfish) fisheries shows a period of higher LPUE just after WWII, with a decrease of 50% in the decade after WWII, suggesting a decrease in biomass of targeted species (Figure 9.6., Lescrauwaet et al. in prep.). From the beginning of the 1960s until 1967, in the period coinciding with the transition from the otter trawl to the more efficient beam trawl and an increase in fishing effort, the LPUE remain around 0.35 kg/HP*Fishing Hour with a slight increase to 0.4 kg/HP*FH in 1967. During the 1970s the fishing effort increases, however the LPUE remains at lower levels (0.15-0.25 kg/HP*FH). As a reference, the analysis conducted for the Belgian fisheries in Iceland, indicated that LPUE values decreased from 0.95 kg/HP*FH in 1946 to 0.24kg/HP*FH in 1983.

Figure 9.6.: Landings per unit of effort (kg/kW*fishing hour), left-hand axis and total fishing effort (kW*fishing hours) by the demersal trawl fisheries on the Belgian part of the North Sea, 1946-1983.

Employment

Little work is conducted on the socio-economic aspects of fisheries and changes in fishing communities. Effects of climate change (change in distribution patterns of target species) or in legal frameworks (quota restrictions) and technical measures (mesh size, change of gear, etc.) can have a profound impact in fishing communities, especially where strong traditions persist to use particular fishing gear and target specific - economically interesting – species.

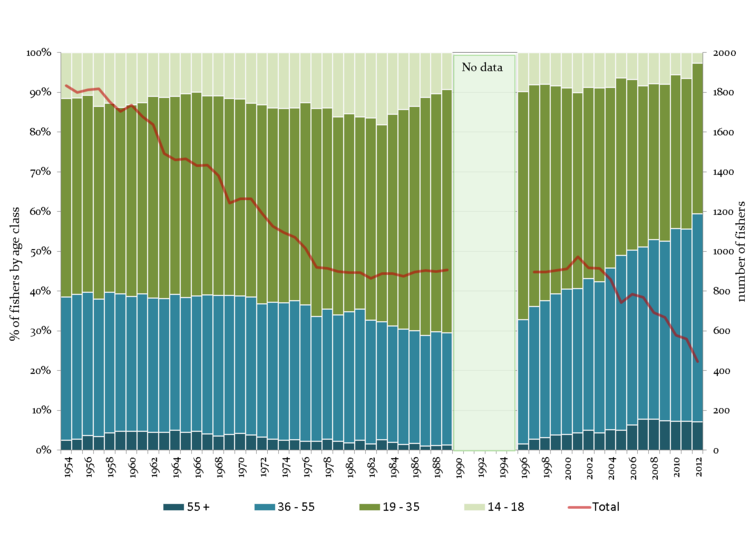

Figure 9.7.: Direct employment in fisheries in Belgium: absolute number of fishers, and proportion by age class, 1954-2012.

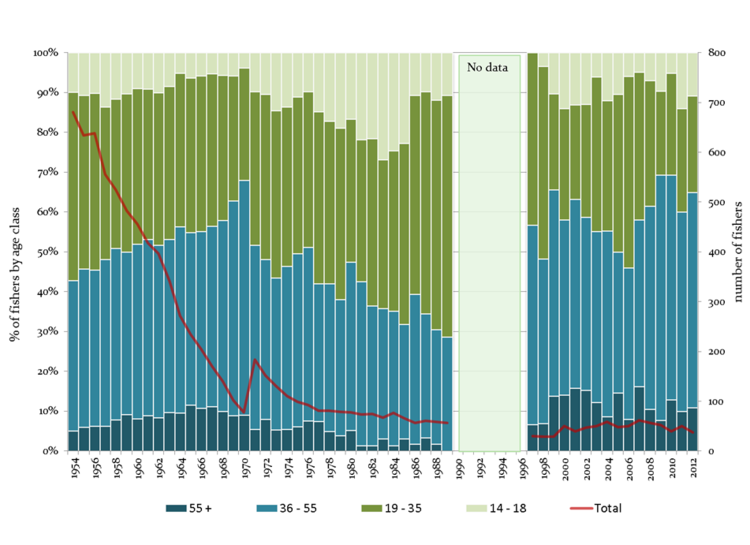

Figure 9.8.: Direct employment in coastal fisheries in Belgium: absolute number of coastal fishers, and proportion by age class, 1954-2012. Note: The sudden increase of coastal fisheries in 1971 is largely due to the change in the definition of ‘coastal fisheries’. Whereas this contained the vessel classes I and II (up to 120HP) before 1971, it was modified to contain all vessels smaller than 35GT in 1971 and later expanded to vessels with engine power <221kW and 70GT that conduct fishing trips of 24 hours maximum (recently expanded to 48 hours)