Difference between revisions of "Testpage4"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''Groundwater management in low- | + | '''Groundwater management in low-lying coastal zones''' |

| − | Groundwater is an important resource for drinking water and irrigation. However, groundwater extraction in low-lying coastal zones is highly problematic. It raises the salinity of the groundwater and | + | Groundwater is an important resource for drinking water and irrigation. However, groundwater extraction in low-lying coastal zones is highly problematic. It raises the salinity of the groundwater and causes the land to sink. Therefore, groundwater management is a major issue in many low-lying coastal areas. This article focuses on shallow coastal [[aquifer]]s connected to the sea. |

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

* reduced usability of groundwater for irrigation, | * reduced usability of groundwater for irrigation, | ||

* soil salinization detrimental to crop growth, | * soil salinization detrimental to crop growth, | ||

| + | * soil subsidence and increased vulnerability to flooding, | ||

* deterioration of the foundation of buildings by corrosion of concrete, reinforcement and bricks, | * deterioration of the foundation of buildings by corrosion of concrete, reinforcement and bricks, | ||

| − | |||

* danger of collapse of buildings due to soil instability. | * danger of collapse of buildings due to soil instability. | ||

In addition, the anticipated sea level rise and the decrease of recharge, due to climate change and increased water demand in the upstream catchment areas, will further exacerbate the pressures on coastal groundwater systems. | In addition, the anticipated sea level rise and the decrease of recharge, due to climate change and increased water demand in the upstream catchment areas, will further exacerbate the pressures on coastal groundwater systems. | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

[[Image:BalanceSaltFresh.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Fig. 3. A small level difference is sufficient to keep a large fresh water column in balance with a salt water column.]] | [[Image:BalanceSaltFresh.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Fig. 3. A small level difference is sufficient to keep a large fresh water column in balance with a salt water column.]] | ||

| − | Seawater intrudes into the underground of the coastal plain through [[aquifer]]s, permeable soil layers consisting of medium / coarse granular material or porous / fissured rock. Due to its greater density, | + | Seawater intrudes into the underground of the coastal plain through [[aquifer]]s, permeable soil layers consisting of medium / coarse granular material or porous / fissured rock. Due to its greater density, seawater enters like a wedge that pushes fresh water inshore, see Fig. 4. A counter-pressure is exerted by the inshore rising fresh water table. Due to the small density difference, a small elevation of the fresh water head is sufficient to keep the seawater intrusion in balance, see Fig. 3. In Fig. 4 it is assumed that the permeability of the underground is the same everywhere. In reality, however, this is never the case due to the presence of poorly permeable layers ([[aquitard]]s); Fig. 5 shows a still much simplified but slightly more realistic image. A rough estimate of the intrusion length <math>L</math> of the seawater wedge into a confined aquifer is given by <ref>Van Dam, J.C. 1983. The shape and position of the salt water wedge in coastal aquifers. Proceedings of the |

| − | of | + | Hamburg Symposium on Relation of Groundwater Quantity and Quality. IAHS Publ. no. 146: 59–75</ref> |

<math>L \approx \alpha k D^2 / (2 Q) , \qquad (1)</math> | <math>L \approx \alpha k D^2 / (2 Q) , \qquad (1)</math> | ||

| − | where <math>\alpha \approx 1/40</math> is the relative density difference, <math>k</math> is the hydraulic conductivity, <math>D</math> is the aquifer depth and <math>Q</math> is the groundwater discharge per unit width. This formula | + | where <math>\alpha \approx 1/40</math> is the relative density difference, <math>k</math> is the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydraulic_conductivity hydraulic conductivity] (related to the permeability), <math>D</math> is the aquifer depth and <math>Q</math> is the groundwater discharge per unit width. This formula applies to a homogeneous confined aquifer of constant depth. The groundwater discharge <math>Q</math> is related to the gradient in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydraulic_head piezometric head] <math>dh/dx</math> according to Darcy's law: <math>Q=-k D dh/dx</math>. |

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| valign="top"| | | valign="top"| | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:IntrusionScheme1.jpg|thumb|left|450px|Fig. 4. Schematic representation of seawater intrusion into a homogeneous coastal aquifer.]] |

| valign="top"| | | valign="top"| | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:IntrusionScheme2.jpg|thumb|left|450px| Fig. 5. Schematic representation of seawater intrusion into a multi-aquifer system.]] |

|} | |} | ||

| − | Seawater intrusion depends, via the groundwater discharge <math>Q</math>, on the elevation difference between the inland fresh water table and the water level at sea. The sea level is variable due to tidal motion and wind set-up / set-down and the inland fresh water table varies over the seasons in response to variable fresh water runoff, evapotranspiration and extractions. These fluctuations in the groundwater pressure gradient, together with spatial inhomogeneities in the geologic structure, contribute to mixing across the fresh-salt interface <ref name=W>Werner, A.D., Bakker, M., Post, V.E.A., Vandenbohede, A., Lu, C., Ataie-Ashtiani, B., Simmons, C.T. and Barry, D.A. 2013. Seawater intrusion processes, investigation and management: Recent advances and future challenges. Advances in Water Resources 51: 3–26</ref>. | + | Seawater intrusion depends, via the groundwater discharge <math>Q</math>, on the elevation difference between the inland fresh water table and the water level at sea. The sea level is variable due to tidal motion and wind set-up / set-down and the inland fresh water table varies over the seasons in response to variable fresh water runoff, evapotranspiration and extractions. These fluctuations in the groundwater pressure gradient, together with spatial inhomogeneities in the geologic structure, contribute to mixing across the fresh-salt interface <ref name=W>Werner, A.D., Bakker, M., Post, V.E.A., Vandenbohede, A., Lu, C., Ataie-Ashtiani, B., Simmons, C.T. and Barry, D.A. 2013. Seawater intrusion processes, investigation and management: Recent advances and future challenges. Advances in Water Resources 51: 3–26</ref>. The rise of the relative sea level is an ongoing trend that gradually increases the seawater intrusion into the underground. Shoreline retreat associated with sea level rise can also play a role. Seawater intrusion is further enhanced in case of a trend-wise decrease of the flux of fresh groundwater to the sea. |

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

* Marine transgression. | * Marine transgression. | ||

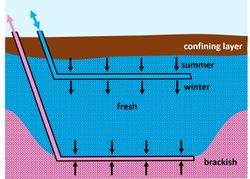

| − | Many coastal areas were flooded by the sea during the Holocene transgression, before sedimentation raised the seafloor above mean high water level and before fluvial processes became dominant. The present saline groundwater was largely formed during this period. Saline intrusion in coastal aquifers by marine transgression occurs today only under extreme storms. Such extreme conditions are rare, but they are expected to become much more frequent in future as a consequence of relative sea level rise (see [[Sea level rise]]). The process of seawater infiltration in a fresh aquifer resulting from a marine flood is shown in Fig. 6. Increased groundwater salinities persist | + | Many coastal areas were flooded by the sea during the Holocene transgression, before sedimentation raised the seafloor above mean high water level and before fluvial processes became dominant. The present saline groundwater was largely formed during this period. Saline intrusion in coastal aquifers by marine transgression occurs today only under extreme storms. Such extreme conditions are rare, but they are expected to become much more frequent in future as a consequence of relative sea level rise (see [[Sea level rise]]). The process of seawater infiltration in a fresh aquifer resulting from a marine flood is shown in Fig. 6. Increased groundwater salinities persist many years after such flood events<ref name=P>Post, V.E.A., Eichholz, M. and Brentführer R. 2018. Groundwater management in coastal zones. Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (BGR). Hannover, Germany, 107 pp.</ref>. |

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

* Groundwater extraction. | * Groundwater extraction. | ||

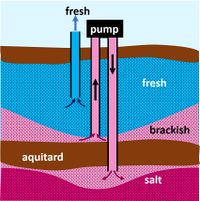

| − | Intensive groundwater extraction increases the intrusion of seawater into the coastal aquifer by diminishing the groundwater discharge to the sea ( | + | Intensive groundwater extraction increases the intrusion of seawater into the coastal aquifer by diminishing the groundwater discharge to the sea (see Eq. 1). This intrusion is a slow process, but with a long-lasting impact. The most immediate effect of pumping up groundwater is the rise of the fresh-salt transition under the well, a phenomenon called 'upconing', see Fig. 8. When a critical limit of the extraction rate is exceeded, the fresh-salt transition rises up to the well mouth and the pumped water becomes brackish. The rise of the fresh-salt transition is strongest in cases where the hydraulic conductivity <math>k</math> of the aquifer is small (low conductivity limits the horizontal groundwater flow towards the well)<ref> Dagan G, Bear J. 1968. Solving the problem of local interface upconing in a coastal aquifer by the method of small perturbations. Journal Hydrological Research 6: 15–44</ref>. For aquifers with a low permeability (small <math>k</math>), only small abstraction rates are possible. |

* Saline seepage. | * Saline seepage. | ||

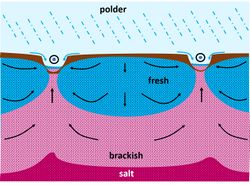

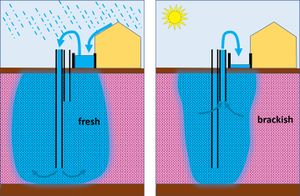

| − | In areas situated below sea level, groundwater can move upwards to the soil surface if the upper soil layer is semipermeable, see Fig. 9 and 10. The upward moving saline seepage water may (1) discharge directly in lakes, canals, ditches or subsurface drain tiles leading to the salinization of surface waters, (2) mix near the surface with shallow fresh groundwater, or even (3) reach the root zone affecting crop growth and natural vegetation. Where rainwater or fresh surface water supplies are limited, saline seepage leads to salinization of surface water and shallow groundwater - a process known as internal salinization. The seepage flow depends on the surface soil level and on the thickness and permeability of the top soil layer. Seepage flow is enhanced at places where ancient sandy deposits are close to the surface or where cracks exist in the top clay layer, giving rise to so-called 'boils' <ref>De Louw, P.G.B., Oude Essink, G.H.P., Stuyfzand, P.J. and Van der Zee, S.E.A.T.M. 2010. Upward groundwater flow in boils as the dominant mechanism of salinization in deep polders, The Netherlands. Journal of Hydrology 394: 494-506</ref>. Seepage in deep polders is increased when the top soil is drained for agricultural purposes | + | In areas situated below sea level, groundwater can move upwards to the soil surface if the upper soil layer is semipermeable, see Fig. 9 and 10. The upward moving saline seepage water may (1) discharge directly in lakes, canals, ditches or subsurface drain tiles leading to the salinization of surface waters, (2) mix near the surface with shallow fresh groundwater, or even (3) reach the root zone affecting crop growth and natural vegetation. Where rainwater or fresh surface water supplies are limited, saline seepage leads to salinization of surface water and shallow groundwater - a process known as internal salinization. The seepage flow depends on the surface soil level and on the thickness and permeability of the top soil layer (Fig. 9). Seepage flow is enhanced at places where ancient sandy deposits are close to the surface or where cracks exist in the top clay layer, giving rise to so-called 'boils' <ref>De Louw, P.G.B., Oude Essink, G.H.P., Stuyfzand, P.J. and Van der Zee, S.E.A.T.M. 2010. Upward groundwater flow in boils as the dominant mechanism of salinization in deep polders, The Netherlands. Journal of Hydrology 394: 494-506</ref>. Seepage in deep polders is increased when the top soil is drained for agricultural purposes (Fig. 10). Compaction of clay and peat soils is another serious consequence of drainage. The effect of seepage on seawater intrusion is similar to the effect of groundwater extraction; it causes upconing of brackish groundwater and increases the intrusion of seawater into the coastal aquifer. |

{| border="0" | {| border="0" | ||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

1. Horizontal wells. | 1. Horizontal wells. | ||

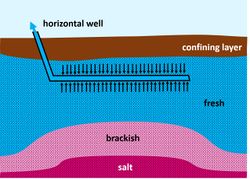

| − | The risk of upconing of the salt-fresh interface can be reduced by 'skimming' the fresh water lens with a horizontal well, see Fig. 12. | + | The risk of upconing of the salt-fresh interface can be reduced by 'skimming' the fresh water lens with a horizontal well, see Fig. 12. In this way it is possible to exploit a brackish aquifer with a relatively thin fresh water lens. Periodically, natural (or artificial) recharge of the fresh water lens is necessary to get the salt-fresh interface back to its former position. |

2. Fresh water storage by infiltration. | 2. Fresh water storage by infiltration. | ||

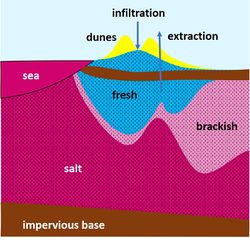

| − | According to the principle shown in Fig. 3, a large fresh water reservoir can be created in the subsoil by raising the fresh water table. This principle can be applied in coastal zones protected by a dune belt. By infiltrating fresh water in the dunes – rain water or fresh water from other sources – the fresh water table can be raised such that a large column of fresh water in the subsoil is kept in hydrostatic balance with the seawater, due to the different densities (Fig. 13). If present, any protruding thick sandy deposit in the coastal zone (e.g., relic channel bars) can serve for fresh water storage in a similar way. Dune infiltration is widely used in the Netherlands to provide drinking water to coastal cities (e.g., Amsterdam, The Hague). | + | According to the principle shown in Fig. 3, a large fresh water reservoir can be created in the subsoil by raising the fresh water table. This principle can be applied in coastal zones protected by a dune belt. By infiltrating fresh water in the dunes – rain water or fresh water from other sources – the fresh water table can be raised such that a large column of fresh water in the subsoil is kept in hydrostatic balance with the seawater, due to the different densities (Fig. 13). If present, any other protruding thick sandy deposit in the coastal zone (e.g., relic channel bars) can serve for fresh water storage in a similar way. Dune infiltration is widely used in the Netherlands to provide drinking water to coastal cities (e.g., Amsterdam, The Hague). |

{| border="0" | {| border="0" | ||

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

4. Aquifer barriers to prevent seawater intrusion. | 4. Aquifer barriers to prevent seawater intrusion. | ||

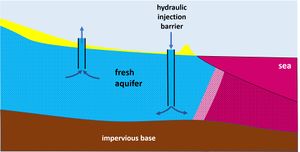

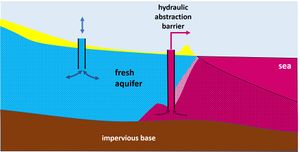

| − | Two types of barriers have been implemented in practice: hydraulic barriers and physical barriers. The usual principle of a hydraulic barrier is shown in Fig. 17. Fresh water (for example, purified sewage water) is injected into the aquifer close to the seaward boundary to create a pressure head that prevents the intrusion of seawater. Further inland, freshwater can be extracted (to a limited extent) in periods of drought from the fresh aquifer. A practical example is the hydraulic barrier installed in California near Los Angeles <ref>Johnson, T. 2007. Technical Documents on Groundwater and Groundwater Monitoring Battling Seawater Intrusion in the Central and West Coast Basins. WRD Technical Bulletin 13. http://www.wrd.org/engineering/reports/TB13_Fall07_Seawater_Barriers.pdf</ref>. The effectiveness of this solution depends on the availability of fresh water during sufficiently long and frequent periods. Another principle is based on extraction of intruding seawater, as shown in Fig. 18. Drawbacks of this principle are the disposal of the extracted saline or brackish groundwater and the lowering of the piezometric heads, especially in shallow coastal aquifers<ref name=OE></ref>. This latter issue can be mitigated by fresh water injection further landward<ref>Pool, M. and Carrera, J. 2010. Dynamics of negative hydraulic barriers to prevent seawater intrusion. Hydrogeology Journal 18: 95–105</ref>. | + | Two types of barriers have been implemented in practice: hydraulic barriers and physical barriers. The usual principle of a hydraulic barrier is shown in Fig. 17. Fresh water (for example, purified sewage water) is injected into the aquifer close to the seaward boundary to create a pressure head that prevents the intrusion of seawater. Further inland, freshwater can be extracted (to a limited extent) in periods of drought from the fresh aquifer. A practical example is the hydraulic barrier installed in California near Los Angeles <ref>Johnson, T. 2007. Technical Documents on Groundwater and Groundwater Monitoring Battling Seawater Intrusion in the Central and West Coast Basins. WRD Technical Bulletin 13. http://www.wrd.org/engineering/reports/TB13_Fall07_Seawater_Barriers.pdf</ref>. The effectiveness of this solution depends on the availability of fresh water during sufficiently long and frequent periods. Another principle is based on extraction of intruding seawater, as shown in Fig. 18. Drawbacks of this principle are the disposal of the extracted saline or brackish groundwater and the lowering of the piezometric heads, especially in shallow coastal aquifers<ref name=OE>Oude Essink, G.H.P. 2001. Improving fresh groundwater supply-problems and solutions. Ocean & Coastal Management 44: 429–449</ref>. This latter issue can be mitigated by fresh water injection further landward<ref>Pool, M. and Carrera, J. 2010. Dynamics of negative hydraulic barriers to prevent seawater intrusion. Hydrogeology Journal 18: 95–105</ref>. |

| − | Physical subsurface barriers have been constructed in several countries, especially in Japan<ref> Nishigaki, M., Kankam-Yeboah, K. and Komatsu, M. 2004. Underground dam technology in some parts of the world. Journal of Groundwater Hydrology 46: 113-130</ref> and China <ref> Wang, K., Li, B., Yu, Q. and Wang, J. 2012. The construction of underground reservoir and its beneficial effect on resource and environment in Shandong Province Peninsula. In: China Geological Survey – Achievements. http://en.cgs.gov.cn/achievements/201601/t20160112_35475.html</ref>. The barriers | + | Physical subsurface barriers have been constructed in several countries, especially in Japan<ref> Nishigaki, M., Kankam-Yeboah, K. and Komatsu, M. 2004. Underground dam technology in some parts of the world. Journal of Groundwater Hydrology 46: 113-130</ref> and China <ref> Wang, K., Li, B., Yu, Q. and Wang, J. 2012. The construction of underground reservoir and its beneficial effect on resource and environment in Shandong Province Peninsula. In: China Geological Survey – Achievements. http://en.cgs.gov.cn/achievements/201601/t20160112_35475.html</ref>. The barriers are generally built of concrete using grouting techniques or mixed-in-place slurry-wall methods<ref>Ishida, S., Tsuchihara, T., Yoshimoto, S. and Imaizumi, M. 2011. Sustainable use of groundwater with underground dams. In: Japan Agricultural Research Quarterly 45: 51-61</ref>. The dams serve as a barrier for seawater intrusion, and also create underground fresh water storage in periods of strong precipitation (Fig. 19). However, the costs are high and the solution is only applicable in shallow aquifers<ref name=OE></ref>. |

{| border="0" | {| border="0" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| valign="top"| | | valign="top"| | ||

| − | [[File:HydraulicInjectionBarrier.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Fig. 17. Hydraulic injection barrier at the seaward entrance of an aquifer. The marine salt wedge is expelled in periods of abundant fresh water. Inland abstraction wells | + | [[File:HydraulicInjectionBarrier.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Fig. 17. Hydraulic injection barrier at the seaward entrance of an aquifer. The marine salt wedge is expelled in periods of abundant fresh water. Inland abstraction wells can be exploited in periods of drought.]] |

| valign="top"| | | valign="top"| | ||

| − | [[File:HydraulicAbstractionBarrier.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Fig. 18. Hydraulic abstraction barrier at the seaward entrance of an aquifer. The marine salt wedge is expelled in periods of abundant fresh water. | + | [[File:HydraulicAbstractionBarrier.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Fig. 18. Hydraulic abstraction barrier at the seaward entrance of an aquifer. The marine salt wedge is expelled in periods of abundant fresh water. Piezometric levels condition the use of inland injection/abstraction wells.]] |

| valign="top"| | | valign="top"| | ||

[[File:PhysicalBarrier.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Fig. 19. Physical subsurface barrier at the seaward entrance of an aquifer.]] | [[File:PhysicalBarrier.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Fig. 19. Physical subsurface barrier at the seaward entrance of an aquifer.]] | ||

| Line 146: | Line 146: | ||

5. Isolating saline areas. | 5. Isolating saline areas. | ||

| − | Saline seepage due to local boils – a major salinization mechanism in the deep polders in the Netherlands – is combated by building a bypass around the saline areas. | + | Saline seepage due to local boils – a major salinization mechanism in the deep polders in the Netherlands – is combated by building a bypass around the saline areas. The temporary isolation (during dry periods) of saline areas with a significant number of boils is controlled by automatic weirs<ref>Kamps, P., Nienhuis, P., van den Heuvel, D. and de Joode, H. 2016. Monitoring Well Optimization for Surveying the Fresh/Saline Groundwater Interface in the Amsterdam Water Supply Dunes. 24th Salt Water Intrusion Meeting and the 4th Asia-Pacific Coastal Aquifer Management Meeting, July 2016, Cairns, Australia</ref>. The temporarily stored salt water is discharged during rainstorm events when salt concentrations are low. Boils that arise from the removal of structures, such as level filters or sheet piles, or from the sealing of old gas wells, can be sealed. This can be done through injection of expanding and persisting fluids or through biosealing; the latter option is the most environmentally friendly. |

| Line 156: | Line 156: | ||

==Groundwater modelling and observation== | ==Groundwater modelling and observation== | ||

[[Image:AirborneTEM.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Fig. 21. SkyTEM team recording Time Domain Electromagnetic Data. Source: G. Oude Essink, https://publicwiki.deltares.nl/ ]] | [[Image:AirborneTEM.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Fig. 21. SkyTEM team recording Time Domain Electromagnetic Data. Source: G. Oude Essink, https://publicwiki.deltares.nl/ ]] | ||

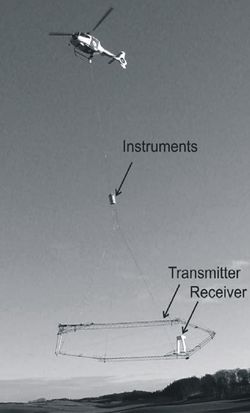

| − | Groundwater flow can be described with | + | Groundwater flow can be described with Darcy's law that couples the flow rate linearly to the gradient in the hydrostatic groundwater pressure. Application of Darcy's law requires knowledge of the soil permeability (generally expressed in terms of hydraulic conductivity). The permeability is different for each soil type. The structure and composition of the substrate is generally very complex. It is a reflection of the geological history in which a large number of processes on very diverse space and time scales play a role. The reliability with which groundwater flows can be simulated therefore depends primarily on the extent to which the structure and composition of the subsoil are known. This knowledge usually has large gaps, since sampling the subsurface over great depth requires a great deal of effort and is very expensive. In addition to knowledge of the subsurface structure, knowledge is needed of the position of the salt-fresh transition zones in the underground. Missing knowledge can be partially overcome by model calibration based on data from wells (quantity and quality of abstractions), piezometric surveys (groundwater pressure) and observations based on geophysical techniques. |

[[Image:ElectricalResistivity.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Fig. 20. Electrical resistivity measurement by continuous vertical electrical sounding. Credit: P. de Louw.]] | [[Image:ElectricalResistivity.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Fig. 20. Electrical resistivity measurement by continuous vertical electrical sounding. Credit: P. de Louw.]] | ||

| − | In recent decades, a large number of geophysical measurement methods have been developed that indirectly provide information about the subsurface soil structure and groundwater salinity and distribution<ref>Herckenrath, D. 2012. Informing groundwater models with near-surface geophysical data. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark</ref>. Seismic techniques, such as Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR <ref>Knight, R. 2001. Ground penetrating radar for environmental applications. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 29L 229-255</ref><ref>Huisman, J., Hubbard, S., Redman, J. and Annan, A. 2003. Measuring Soil Water Content with Ground Penetrating Radar: A Review. Vadose Zone Journal 2: 476-491</ref>) can be used for detecting and mapping structures in the underground. Unfortunately, this technique is less suitable for saturated soils with a high clay content. Nuclear Magnetic techniques, such as Magnetic Resonance Sounding (MRS <ref>Legchenko, A., Baltassat, J. M., Beauce, A. and Bernard, J. 2002. Nuclear magnetic resonance as a geophysical tool for hydrogeologists. Journal of Applied Geophysics 50: 21-46</ref>) and Time Lapse Gravity (TLG <ref> Montgomery, E.L. 1971. Determination of coefficient of storage by use of gravity measurements: Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, 144 p</ref>) can provide information on aquifer properties, such as moisture content, porosity and hydraulic conductivity. Electrical resistivity (Fig. 20) and electromagnetic techniques (Fig. 21) make use of the large electrical resistivity contrast between seawater and freshwater for detecting and mapping the subsurface salinity distribution <ref>Macaulay, S. and Mullen, I. 2007. Predicting salinity impacts of land-use change: Groundwater modelling with airborne electromagnetics and field data, SE Queensland, Australia, International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 9: 124-129</ref>. Examples are Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT <ref> | + | In recent decades, a large number of geophysical measurement methods have been developed that indirectly provide information about the subsurface soil structure and groundwater salinity and distribution<ref>Herckenrath, D. 2012. Informing groundwater models with near-surface geophysical data. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark</ref>. Seismic techniques, such as Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR <ref>Knight, R. 2001. Ground penetrating radar for environmental applications. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 29L 229-255</ref><ref>Huisman, J., Hubbard, S., Redman, J. and Annan, A. 2003. Measuring Soil Water Content with Ground Penetrating Radar: A Review. Vadose Zone Journal 2: 476-491</ref>) can be used for detecting and mapping structures in the underground. Unfortunately, this technique is less suitable for saturated soils with a high clay content. Nuclear Magnetic techniques, such as Magnetic Resonance Sounding (MRS <ref>Legchenko, A., Baltassat, J. M., Beauce, A. and Bernard, J. 2002. Nuclear magnetic resonance as a geophysical tool for hydrogeologists. Journal of Applied Geophysics 50: 21-46</ref>) and Time Lapse Gravity (TLG <ref> Montgomery, E.L. 1971. Determination of coefficient of storage by use of gravity measurements: Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, 144 p</ref>) can provide information on aquifer properties, such as moisture content, porosity and hydraulic conductivity. Electrical resistivity (Fig. 20) and electromagnetic techniques (Fig. 21) make use of the large electrical resistivity contrast between seawater and freshwater for detecting and mapping the subsurface salinity distribution <ref>Macaulay, S. and Mullen, I. 2007. Predicting salinity impacts of land-use change: Groundwater modelling with airborne electromagnetics and field data, SE Queensland, Australia, International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 9: 124-129</ref>. Examples are Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT <ref>Acworth, R.I. and Dasey, G.R. 2003. Mapping of the hyporheic zone around a tidal creek using a combination of borehole logging, borehole electrical tomography and cross-creek electrical imaging, New South Wales, Australia. Hydrogeology Journal 11: 368–77</ref>), Time-Lapse Resistivity (TLR<ref> Poulsen, S.E., Rasmussen, K.R., Christensen, N.B. and Christensen, S. 2010. Evaluating the salinity distribution of a shallow coastal aquifer by vertical multielectrode profiling (Denmark). Hydrogeology Journal 2010: 161–71</ref>), Time Domain Electromagnetic sounding (TDEM <ref>Auken, E., Christiansen, A. V., Jacobsen, L. H. and Sorensen, K. I. 2008. A resolution study of buried valleys using laterally constrained inversion of TEM data. Journal of Applied Geophysics 65: 10-20</ref>), and Induced Polarization (IP <ref>Dahlin, T., Leroux, V. and Nissen, J. 2002. Measuring techniques in induced polarisation imaging. Journal of Applied Geophysics 50: 279– 298</ref>). Together with information from wells, bore holes and model calculations these data enable reasonable estimates of the effect of interventions in the groundwater system. However, the design of groundwater models and the interpretation of model results still require highly specialized knowledge and experience of geohydrological processes. |

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 16:48, 6 April 2020

Groundwater management in low-lying coastal zones

Groundwater is an important resource for drinking water and irrigation. However, groundwater extraction in low-lying coastal zones is highly problematic. It raises the salinity of the groundwater and causes the land to sink. Therefore, groundwater management is a major issue in many low-lying coastal areas. This article focuses on shallow coastal aquifers connected to the sea.

Contents

Threats of groundwater extraction

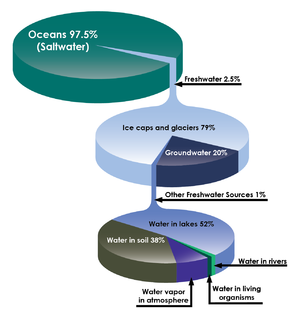

Fresh water represents only a small fraction of earth's water resource – less than 1%, ice excluded (Fig. 1). Groundwater is by far the most important fresh water resource available for human use. More than 50% of world’s population lives in coastal areas and is largely dependent on fresh groundwater resources for domestic, agricultural and industrial purposes. The exploitation of fresh groundwater resources is sharply increasing as a consequence of population growth, economic growth, intensified agricultural development, and the degradation of surface water resources due to contamination (Fig. 2).

Worldwide, many large coastal cities have expanded into low coastal plains during the past decades, especially in Asia and Africa (see Coastal cities and sea level rise). Most of these plains emerged after the Holocene marine transgression, when the seabed was raised above sea level by sedimentation behind a sheltering coastal barrier. These deposits form a top soil layer of a few meters up to several tens of meters thick, and contain a high fraction of fine sediments of fluvial and marine origin (and peat, in humid climatic zones). On these poorly draining soils, which are highly susceptible to compaction, extensive urban and industrial development has taken place[3]. The land elevation is generally close to the mean high sea level. However, in many areas it is lower and still subsiding, mainly as a result of drainage and groundwater extraction[4].

Intensive groundwater extraction from underlying water-bearing layers (aquifers) stimulates the intrusion of seawater, leading to increased groundwater salinity[5]. In the lowest areas, brackish groundwater may reach the surface by upward groundwater flow through the confining top layer, so-called 'saline seepage'. The threats of uncontrolled groundwater extraction can remain unnoticed for many years because groundwater flow is a slow process. However, in the long run they are considerable [6]:

- unsuitability of groundwater for drinking water,

- reduced usability of groundwater for irrigation,

- soil salinization detrimental to crop growth,

- soil subsidence and increased vulnerability to flooding,

- deterioration of the foundation of buildings by corrosion of concrete, reinforcement and bricks,

- danger of collapse of buildings due to soil instability.

In addition, the anticipated sea level rise and the decrease of recharge, due to climate change and increased water demand in the upstream catchment areas, will further exacerbate the pressures on coastal groundwater systems.

Salt intrusion processes

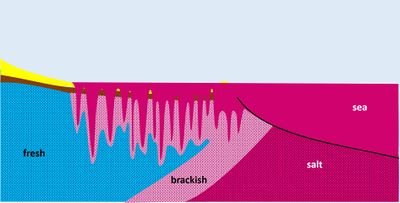

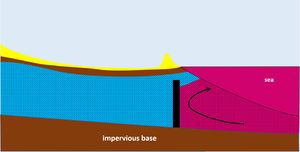

Seawater intrudes into the underground of the coastal plain through aquifers, permeable soil layers consisting of medium / coarse granular material or porous / fissured rock. Due to its greater density, seawater enters like a wedge that pushes fresh water inshore, see Fig. 4. A counter-pressure is exerted by the inshore rising fresh water table. Due to the small density difference, a small elevation of the fresh water head is sufficient to keep the seawater intrusion in balance, see Fig. 3. In Fig. 4 it is assumed that the permeability of the underground is the same everywhere. In reality, however, this is never the case due to the presence of poorly permeable layers (aquitards); Fig. 5 shows a still much simplified but slightly more realistic image. A rough estimate of the intrusion length [math]L[/math] of the seawater wedge into a confined aquifer is given by [7]

[math]L \approx \alpha k D^2 / (2 Q) , \qquad (1)[/math]

where [math]\alpha \approx 1/40[/math] is the relative density difference, [math]k[/math] is the hydraulic conductivity (related to the permeability), [math]D[/math] is the aquifer depth and [math]Q[/math] is the groundwater discharge per unit width. This formula applies to a homogeneous confined aquifer of constant depth. The groundwater discharge [math]Q[/math] is related to the gradient in the piezometric head [math]dh/dx[/math] according to Darcy's law: [math]Q=-k D dh/dx[/math].

|

File:IntrusionScheme1.jpg Fig. 4. Schematic representation of seawater intrusion into a homogeneous coastal aquifer. |

File:IntrusionScheme2.jpg Fig. 5. Schematic representation of seawater intrusion into a multi-aquifer system. |

Seawater intrusion depends, via the groundwater discharge [math]Q[/math], on the elevation difference between the inland fresh water table and the water level at sea. The sea level is variable due to tidal motion and wind set-up / set-down and the inland fresh water table varies over the seasons in response to variable fresh water runoff, evapotranspiration and extractions. These fluctuations in the groundwater pressure gradient, together with spatial inhomogeneities in the geologic structure, contribute to mixing across the fresh-salt interface [8]. The rise of the relative sea level is an ongoing trend that gradually increases the seawater intrusion into the underground. Shoreline retreat associated with sea level rise can also play a role. Seawater intrusion is further enhanced in case of a trend-wise decrease of the flux of fresh groundwater to the sea.

Several other processes contribute to salinization of coastal aquifers.

- Marine transgression.

Many coastal areas were flooded by the sea during the Holocene transgression, before sedimentation raised the seafloor above mean high water level and before fluvial processes became dominant. The present saline groundwater was largely formed during this period. Saline intrusion in coastal aquifers by marine transgression occurs today only under extreme storms. Such extreme conditions are rare, but they are expected to become much more frequent in future as a consequence of relative sea level rise (see Sea level rise). The process of seawater infiltration in a fresh aquifer resulting from a marine flood is shown in Fig. 6. Increased groundwater salinities persist many years after such flood events[9].

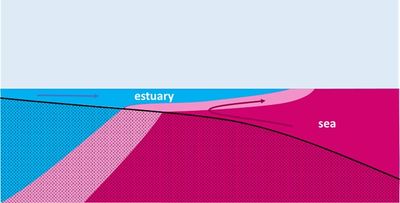

- Seawater intrusion via estuaries.

Coastal aquifers are not only in contact with salt water at the land-sea boundary but often also with salt water of estuaries. In this way, intrusion of saline surface water into shallow groundwater can take place further inland (Fig. 7). The intrusion of seawater in estuaries is discussed in the articles Seawater intrusion and mixing in estuaries and Estuarine circulation. Seawater intrusion in estuaries has strongly increased during the past century due to channel deepening (dredging) for navigational purposes. The greatest incursion of high salinity seawater occurs in periods of low fluvial runoff, especially in microtidal estuaries (see Salt wedge estuaries).

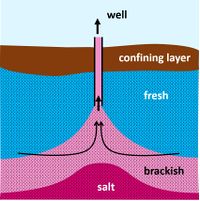

- Groundwater extraction.

Intensive groundwater extraction increases the intrusion of seawater into the coastal aquifer by diminishing the groundwater discharge to the sea (see Eq. 1). This intrusion is a slow process, but with a long-lasting impact. The most immediate effect of pumping up groundwater is the rise of the fresh-salt transition under the well, a phenomenon called 'upconing', see Fig. 8. When a critical limit of the extraction rate is exceeded, the fresh-salt transition rises up to the well mouth and the pumped water becomes brackish. The rise of the fresh-salt transition is strongest in cases where the hydraulic conductivity [math]k[/math] of the aquifer is small (low conductivity limits the horizontal groundwater flow towards the well)[10]. For aquifers with a low permeability (small [math]k[/math]), only small abstraction rates are possible.

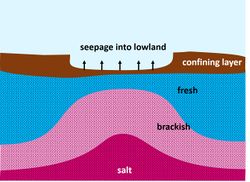

- Saline seepage.

In areas situated below sea level, groundwater can move upwards to the soil surface if the upper soil layer is semipermeable, see Fig. 9 and 10. The upward moving saline seepage water may (1) discharge directly in lakes, canals, ditches or subsurface drain tiles leading to the salinization of surface waters, (2) mix near the surface with shallow fresh groundwater, or even (3) reach the root zone affecting crop growth and natural vegetation. Where rainwater or fresh surface water supplies are limited, saline seepage leads to salinization of surface water and shallow groundwater - a process known as internal salinization. The seepage flow depends on the surface soil level and on the thickness and permeability of the top soil layer (Fig. 9). Seepage flow is enhanced at places where ancient sandy deposits are close to the surface or where cracks exist in the top clay layer, giving rise to so-called 'boils' [11]. Seepage in deep polders is increased when the top soil is drained for agricultural purposes (Fig. 10). Compaction of clay and peat soils is another serious consequence of drainage. The effect of seepage on seawater intrusion is similar to the effect of groundwater extraction; it causes upconing of brackish groundwater and increases the intrusion of seawater into the coastal aquifer.

- Irrigation practices.

In arid coastal plains where the groundwater salinity is too high, crops must be irrigated with water that is supplied from elsewhere. Due to water scarcity, the infiltrated irrigation water is collected in special drains and re-used for irrigation. Such an irrigation system exists, for example, in the Nile Delta [12]. Because the irrigation water is mixed with brackish groundwater, re-use can cause, in combination with evapotranspiration, a net salt flux to the land surface.

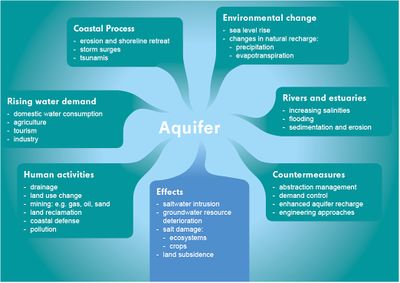

Groundwater management

Groundwater management requires an integrated approach based on insight into the multiple factors that influence the groundwater system, see Fig. 11. This insight is usually fragmentary due to the complexity of the groundwater system. Groundwater flow models are crucial for estimating the influence of abstractions on the groundwater status, see section Groundwater modelling. Permits, metering of wells, quotas and water taxes are the legal instruments on which sustainable groundwater management can be based, together with obligations of monitoring and reporting. Polluting substances from point sources (industrial effluents, household sewage) and from diffuse sources (agricultural effluents containing pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers) are a major danger for groundwater contamination. Adequate environmental policy, agricultural policy, and spatial policy that tackle the pollution issue are prerequisite for sustainable groundwater management. The effectiveness of groundwater management can be increased by involving local stakeholders, due to the strong link between use and usability of the groundwater resource. Understanding and support from stakeholders makes it easier to enforce legal rules and provisions. Without support of stakeholders, enforcement is usually difficult to achieve [13].

Monitoring aquifers for protection against depletion and pollution is a technically demanding and costly exercise so that information about aquifers is often incomplete. The costs for setting up a monitoring network, collecting data regularly, processing, interpreting, and storing it in databases, including unified databases at the national level, are one of the reasons why in developed and developing countries alike water rights and monitoring obligations, especially with respect to groundwater, may remain unimplemented [13].

Measures to reduce soil and groundwater salinization

Different types of measures are possible to reduce soil and groundwater salinization, which can be applied depending on the geological setting and the causes of salt intrusion.

1. Horizontal wells.

The risk of upconing of the salt-fresh interface can be reduced by 'skimming' the fresh water lens with a horizontal well, see Fig. 12. In this way it is possible to exploit a brackish aquifer with a relatively thin fresh water lens. Periodically, natural (or artificial) recharge of the fresh water lens is necessary to get the salt-fresh interface back to its former position.

2. Fresh water storage by infiltration.

According to the principle shown in Fig. 3, a large fresh water reservoir can be created in the subsoil by raising the fresh water table. This principle can be applied in coastal zones protected by a dune belt. By infiltrating fresh water in the dunes – rain water or fresh water from other sources – the fresh water table can be raised such that a large column of fresh water in the subsoil is kept in hydrostatic balance with the seawater, due to the different densities (Fig. 13). If present, any other protruding thick sandy deposit in the coastal zone (e.g., relic channel bars) can serve for fresh water storage in a similar way. Dune infiltration is widely used in the Netherlands to provide drinking water to coastal cities (e.g., Amsterdam, The Hague).

3. Fresh water storage by injection.

Collected rainwater – or fresh water from other sources – can temporarily be stored in the subsoil for later re-use. Fresh water is injected into the deeper part of the aquifer and collected later from a higher pumping well, as shown in Fig. 14. A larger volume of fresh water can be stored by lowering the salt-fresh interface. Salt groundwater is pumped away from greater depth to reduce the hydrostatic pressure on the surface layer. This will prevent an existing freshwater lens from being pushed out[14]. The brackish/salt water has to be discharged to the sea or it can be treated in a desalination plant for re-use[15]. The extraction-injection is adjusted by a so-called automatic 'freshmaker system'[14]. The principle is shown schematically in Fig. 15. Another option (if technically and economically feasible) is to pump the brackish/salt water through the underlying aquitard to a lower aquifer ('freshkeeper system'[14]), see Fig. 16.

4. Aquifer barriers to prevent seawater intrusion.

Two types of barriers have been implemented in practice: hydraulic barriers and physical barriers. The usual principle of a hydraulic barrier is shown in Fig. 17. Fresh water (for example, purified sewage water) is injected into the aquifer close to the seaward boundary to create a pressure head that prevents the intrusion of seawater. Further inland, freshwater can be extracted (to a limited extent) in periods of drought from the fresh aquifer. A practical example is the hydraulic barrier installed in California near Los Angeles [16]. The effectiveness of this solution depends on the availability of fresh water during sufficiently long and frequent periods. Another principle is based on extraction of intruding seawater, as shown in Fig. 18. Drawbacks of this principle are the disposal of the extracted saline or brackish groundwater and the lowering of the piezometric heads, especially in shallow coastal aquifers[17]. This latter issue can be mitigated by fresh water injection further landward[18]. Physical subsurface barriers have been constructed in several countries, especially in Japan[19] and China [20]. The barriers are generally built of concrete using grouting techniques or mixed-in-place slurry-wall methods[21]. The dams serve as a barrier for seawater intrusion, and also create underground fresh water storage in periods of strong precipitation (Fig. 19). However, the costs are high and the solution is only applicable in shallow aquifers[17].

5. Isolating saline areas.

Saline seepage due to local boils – a major salinization mechanism in the deep polders in the Netherlands – is combated by building a bypass around the saline areas. The temporary isolation (during dry periods) of saline areas with a significant number of boils is controlled by automatic weirs[22]. The temporarily stored salt water is discharged during rainstorm events when salt concentrations are low. Boils that arise from the removal of structures, such as level filters or sheet piles, or from the sealing of old gas wells, can be sealed. This can be done through injection of expanding and persisting fluids or through biosealing; the latter option is the most environmentally friendly.

Dealing with brackish groundwater

In arid coastal zones with endemic freshwater shortages, there are no good options for preventing salt intrusion into the groundwater. Strict regulation of groundwater abstraction is necessary to make land use possible. Agriculture has to make use of salt-tolerant crops. Fortunately, ever better crops are being developed for saline conditions, including by genetic modification techniques[23][24]. In addition, infrastructure must be protected against corrosion by saline groundwater, including the use of salt-resistant concrete.

Groundwater modelling and observation

Groundwater flow can be described with Darcy's law that couples the flow rate linearly to the gradient in the hydrostatic groundwater pressure. Application of Darcy's law requires knowledge of the soil permeability (generally expressed in terms of hydraulic conductivity). The permeability is different for each soil type. The structure and composition of the substrate is generally very complex. It is a reflection of the geological history in which a large number of processes on very diverse space and time scales play a role. The reliability with which groundwater flows can be simulated therefore depends primarily on the extent to which the structure and composition of the subsoil are known. This knowledge usually has large gaps, since sampling the subsurface over great depth requires a great deal of effort and is very expensive. In addition to knowledge of the subsurface structure, knowledge is needed of the position of the salt-fresh transition zones in the underground. Missing knowledge can be partially overcome by model calibration based on data from wells (quantity and quality of abstractions), piezometric surveys (groundwater pressure) and observations based on geophysical techniques.

In recent decades, a large number of geophysical measurement methods have been developed that indirectly provide information about the subsurface soil structure and groundwater salinity and distribution[25]. Seismic techniques, such as Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR [26][27]) can be used for detecting and mapping structures in the underground. Unfortunately, this technique is less suitable for saturated soils with a high clay content. Nuclear Magnetic techniques, such as Magnetic Resonance Sounding (MRS [28]) and Time Lapse Gravity (TLG [29]) can provide information on aquifer properties, such as moisture content, porosity and hydraulic conductivity. Electrical resistivity (Fig. 20) and electromagnetic techniques (Fig. 21) make use of the large electrical resistivity contrast between seawater and freshwater for detecting and mapping the subsurface salinity distribution [30]. Examples are Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT [31]), Time-Lapse Resistivity (TLR[32]), Time Domain Electromagnetic sounding (TDEM [33]), and Induced Polarization (IP [34]). Together with information from wells, bore holes and model calculations these data enable reasonable estimates of the effect of interventions in the groundwater system. However, the design of groundwater models and the interpretation of model results still require highly specialized knowledge and experience of geohydrological processes.

References

- ↑ pbslearningmedia https://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/buac17-35-sci-ess-waterdistribute/saltwater-and-freshwater-distribution-on-earth/

- ↑ WWAP (United Nations World Water Assessment Programme). 2015. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2015: Water for a Sustainable World. Paris, UNESCO https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000231823

- ↑ Jiao, J. and Post, V. 2019. Coastal Hydrogeology. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Syvitski, J. P., Kettner, A. J., Overeem, I., Hutton, E. W., Hannon, M. T., Brakenridge, G. R. and Nicholls R. J. 2009. Sinking deltas due to human activities. Nature Geoscience 2: 681-686

- ↑ Custodio, E. and Bruggeman, G.A., editors. Groundwater problems in coastal areas: a contribution to the International Hydrological Programme. Studies and reports in hydrology, vol. 45. Paris: UNESCO; 1987

- ↑ Post, V.E.A., Eichholz, M. and Brentführer R. 2018. Groundwater management in coastal zones. Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (BGR). Hannover, Germany, 107 pp.

- ↑ Van Dam, J.C. 1983. The shape and position of the salt water wedge in coastal aquifers. Proceedings of the Hamburg Symposium on Relation of Groundwater Quantity and Quality. IAHS Publ. no. 146: 59–75

- ↑ Werner, A.D., Bakker, M., Post, V.E.A., Vandenbohede, A., Lu, C., Ataie-Ashtiani, B., Simmons, C.T. and Barry, D.A. 2013. Seawater intrusion processes, investigation and management: Recent advances and future challenges. Advances in Water Resources 51: 3–26

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Post, V.E.A., Eichholz, M. and Brentführer R. 2018. Groundwater management in coastal zones. Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (BGR). Hannover, Germany, 107 pp.

- ↑ Dagan G, Bear J. 1968. Solving the problem of local interface upconing in a coastal aquifer by the method of small perturbations. Journal Hydrological Research 6: 15–44

- ↑ De Louw, P.G.B., Oude Essink, G.H.P., Stuyfzand, P.J. and Van der Zee, S.E.A.T.M. 2010. Upward groundwater flow in boils as the dominant mechanism of salinization in deep polders, The Netherlands. Journal of Hydrology 394: 494-506

- ↑ Kotb, T.H.S., Watanabe, T., Ogino, Y. and Tanji, K.K. 2000. Soil salinization in the Nile Delta and related policy issues in Egypt. Agricultural Water Management 43: 239-261

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mechlem, K. 2016. Groundwater Governance: The Role of Legal Frameworks at the Local and National Level—Established Practice and Emerging Trends. Water 2016, 8, 347; doi:10.3390/w8080347

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Zuurbier, K. G., Kooiman, J. W., Groen, M. M., Maas, B. and Stuyfzand, P. J. 2014. Enabling successful aquifer storage and recovery (ASR) of freshwater using horizontal directional drilled wells (HDDWs) in coastal aquifers. In: Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 20 (3), B4014003

- ↑ Khadra, W.M., Stuyfzand, P.J. and Khadra, I.M. 2017. Mitigation of saltwater intrusion by ‘integrated fresh-keeper’ wells combined with high recovery reverse osmosis. Science of The Total Environment 574: 796-805

- ↑ Johnson, T. 2007. Technical Documents on Groundwater and Groundwater Monitoring Battling Seawater Intrusion in the Central and West Coast Basins. WRD Technical Bulletin 13. http://www.wrd.org/engineering/reports/TB13_Fall07_Seawater_Barriers.pdf

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Oude Essink, G.H.P. 2001. Improving fresh groundwater supply-problems and solutions. Ocean & Coastal Management 44: 429–449

- ↑ Pool, M. and Carrera, J. 2010. Dynamics of negative hydraulic barriers to prevent seawater intrusion. Hydrogeology Journal 18: 95–105

- ↑ Nishigaki, M., Kankam-Yeboah, K. and Komatsu, M. 2004. Underground dam technology in some parts of the world. Journal of Groundwater Hydrology 46: 113-130

- ↑ Wang, K., Li, B., Yu, Q. and Wang, J. 2012. The construction of underground reservoir and its beneficial effect on resource and environment in Shandong Province Peninsula. In: China Geological Survey – Achievements. http://en.cgs.gov.cn/achievements/201601/t20160112_35475.html

- ↑ Ishida, S., Tsuchihara, T., Yoshimoto, S. and Imaizumi, M. 2011. Sustainable use of groundwater with underground dams. In: Japan Agricultural Research Quarterly 45: 51-61

- ↑ Kamps, P., Nienhuis, P., van den Heuvel, D. and de Joode, H. 2016. Monitoring Well Optimization for Surveying the Fresh/Saline Groundwater Interface in the Amsterdam Water Supply Dunes. 24th Salt Water Intrusion Meeting and the 4th Asia-Pacific Coastal Aquifer Management Meeting, July 2016, Cairns, Australia

- ↑ De Vos, A., Bruning, B., Van Straten, G., Oosterbaan, R., Rozema, J. and Van Bodegom, P. 2016. Crop salt tolerance. Salt Farm Texel. https://www.salineagricultureworldwide.com/uploads/file_uploads/files/Report_Crop_Salt_Tolerance-Salt_Farm_Texel.pdf

- ↑ Roy, S.J., Negrao, S. and Tester, M. 2014. Salt resistant crop plants. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 26: 115–124

- ↑ Herckenrath, D. 2012. Informing groundwater models with near-surface geophysical data. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark

- ↑ Knight, R. 2001. Ground penetrating radar for environmental applications. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 29L 229-255

- ↑ Huisman, J., Hubbard, S., Redman, J. and Annan, A. 2003. Measuring Soil Water Content with Ground Penetrating Radar: A Review. Vadose Zone Journal 2: 476-491

- ↑ Legchenko, A., Baltassat, J. M., Beauce, A. and Bernard, J. 2002. Nuclear magnetic resonance as a geophysical tool for hydrogeologists. Journal of Applied Geophysics 50: 21-46

- ↑ Montgomery, E.L. 1971. Determination of coefficient of storage by use of gravity measurements: Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, 144 p

- ↑ Macaulay, S. and Mullen, I. 2007. Predicting salinity impacts of land-use change: Groundwater modelling with airborne electromagnetics and field data, SE Queensland, Australia, International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 9: 124-129

- ↑ Acworth, R.I. and Dasey, G.R. 2003. Mapping of the hyporheic zone around a tidal creek using a combination of borehole logging, borehole electrical tomography and cross-creek electrical imaging, New South Wales, Australia. Hydrogeology Journal 11: 368–77

- ↑ Poulsen, S.E., Rasmussen, K.R., Christensen, N.B. and Christensen, S. 2010. Evaluating the salinity distribution of a shallow coastal aquifer by vertical multielectrode profiling (Denmark). Hydrogeology Journal 2010: 161–71

- ↑ Auken, E., Christiansen, A. V., Jacobsen, L. H. and Sorensen, K. I. 2008. A resolution study of buried valleys using laterally constrained inversion of TEM data. Journal of Applied Geophysics 65: 10-20

- ↑ Dahlin, T., Leroux, V. and Nissen, J. 2002. Measuring techniques in induced polarisation imaging. Journal of Applied Geophysics 50: 279– 298