Difference between revisions of "Shoreface nourishment"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

:[[Rip current]] | :[[Rip current]] | ||

:[[Dealing with coastal erosion]] | :[[Dealing with coastal erosion]] | ||

| + | :[[Ecological impacts of seabed sand mining]] | ||

| + | :[[Coastal Hydrodynamics And Transport Processes]] | ||

:[[Experiences with beach nourishments in Portugal]] | :[[Experiences with beach nourishments in Portugal]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:53, 1 November 2025

Definition of Shoreface nourishment:

Artificial sand supply in the subtidal active zone of the coastal profile with sand imported from a source outside the active coastal zone.

This is the common definition for Shoreface nourishment, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

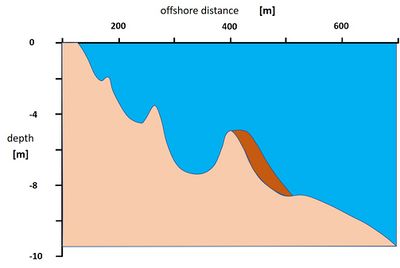

Shoreface nourishments are usually implemented through the placement of a submarine berm against the seaward flank of a nearshore sandbar (Fig. 2). Shoreface nourishments are less costly than beach nourishment. They are primarily intended to stabilize an eroding coast and to halt shoreline retreat. They are less effective for beach widening.

Contents

Why shoreface nourishment

If offshore sand borrow locations are abundant and not far away, the price per m3 of shoreface nourishment is substantially lower than for beach nourishment. Sand can be deposited directly by dredging vessels equipped with rainbowing lances or with a split hull. Intermediate barges and pipelines to supply the sand on the nourishment site are not necessary. The cost-effectiveness of shoreface nourishments is even greater if they are combined with maintenance dredging of nearby navigation channels. Comparison of shoreface nourishments with beach nourishments along the Dutch coast shows that the former are more persistent with a substantially longer lifespan.

Shoreface nourishment programmes contribute to the long-term sand balance of the coastal zone, provided there are no substantial sand losses to deep water, i.e., beyond the seaward boundary of the active coastal zone where almost no wave-induced sand transport occurs. However, estimating long-term net sediment transport to deep water is problematic, as current measurement techniques do not allow for accurate estimates. Nearshore sandbars often tend to migrate offshore in cases where the adjusted Dean number [math]\Omega_{\beta}[/math] is large, see Shoreface profile#Downslope sediment transport. Even in these cases, however, the net sand transport from the upper shoreface to the lower shoreface is probably small. For example, model simulations for the Dutch coast suggest that the net sand transport across the seaward boundary of the active coastal zone (estimated depth of 20 m) is more likely directed landward than seaward[1]. This may also apply for other gently sloping coastal zones situated on wide continental shelves[2]. The long-term positive sand balance of shoreface nourishments therefore creates a sand buffer that is progressively spread over the active coastal zone by longshore and cross-shore transport processes. This contributes to raising the nearshore seabed and mitigating the effect of sea level rise.

Processes

Shoreline accretion landward of a shoreface nourishment is related to two different mechanisms: the leeside effect and the feeder effect.

The leeside effect (also known as reef or breaker bar effect) is related to increased wave dissipation across the nourished sandbar. The smaller waves near the shoreline generate less stirring of the sediment bed and a decrease of the wave-induced undertow current and associated offshore-directed sand transport[3]. With oblique wave incidence, the wave attenuation behind the nourishment induces a gradient in the alongshore sediment transport, resulting in updrift sedimentation and downdrift erosion.

The feeder effect results from the net onshore flux of water over the nourished sandbar (berm). This net onshore flux is due to the occurrence of onshore orbital velocity when the wave crest passes the sandbar, and due to flow acceleration by radiation stress, resulting from wave attenuation over the bar. Onshore sediment transport is further enhanced by increased asymmetry of the waves as they propagate and break over the nourished sandbar. The net onshore transport over the bar also benefits from the attenuation of the offshore-directed undertow current, which is partially deflected along the sandbar toward the tips (lateral extremities) of the nourishment (see also Rip current). The onshore sand flux is partially offset, however, by this rip current circulation toward the sandbar tips and further offshore, with sand loss to deep water.[4] This sand loss is relatively more important for short nourishments.

In summary, both processes, the leeside effect and the feeder effect, produce net accretion in the zone between the shoreline and the nourishment. The leeside effect is strongest for oblique wave incidence, whereas the feeder effect dominates under normal wave incidence. Observations show a slow decline of the nourished sandbar, a slow landward migration of the bar crest, a deepening of the trough landward of the bar and net accretion further nearshore[4]. This observed accretion-erosion pattern is qualitatively consistent with the processes described above.

Observations further show that considerable cross-shore profile change takes place after a shoreface nourishment, while an impact at the adjacent coast is hard to distinguish. A possible shoreline impact can be obscured by natural variability in shoreline positions (e.g. through shoreline features such as sand waves or cusps and storm response).

Shoreline advance and sediment accretion in the subtidal zone may impact the sub-aerial beach and dunes through two mechanisms. First, an increase in sand transport to the beach can result in a wider beach and increased aeolian sediment transport towards the dune due to greater fetch length. Second, the increase in sediment volume lower in the profile reduces the storm impact on the (embryonic) foredunes. These combined effects can yield a seaward migration of the dunefoot. [3]

Experience from shoreface nourishments on the Dutch coast

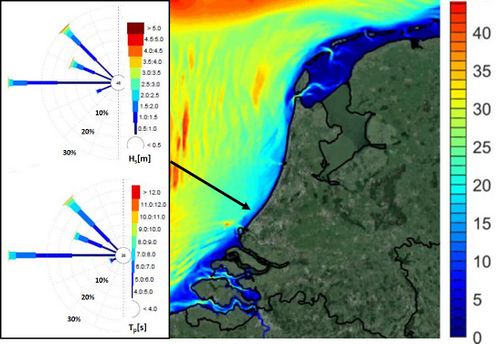

In 1990, the Dutch government has adopted a coastline maintenance policy by means of sand nourishments. From that time, more than 300 nourishments have been carried out, of which 90 shoreface nourishments with a total volume of about 160 Mm3. From the experience of these nourishments some rules of thumb have been derived to optimize the effectiveness of shoreface nourishments. These rules pertain to the Dutch coastal conditions, shown in Fig. 1. Similar conditions are found at sandy coasts along many other shelf seas.

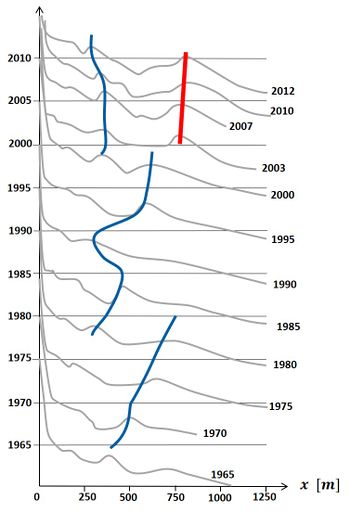

Along the Dutch coast, long-term net shoreline retreat is related to the long-term net offshore migration of nearshore sandbars (see the article Nearshore sandbars). Most shoreface nourishments are applied as an artificial bar just seaward of the outer bar (Fig. 2); in one case the nourishment was placed in the trough between the outer and inner bar. The lifespan of the artificial nourished bar is the time from nourishment until integration of the artificial bar into the original bar pattern and the resumption of the offshore migration cycle.

The evaluation of the nourishments brought forward the following observations about the effects and effectiveness[6][5][7][8], see also Fig. 3:

- The nourishments were effective to stop the offshore bar cycle during the lifespan of the nourishment;

- The lifespan of the nourishments increased with increasing nourishment concentration (the sand volume nourished per meter);

- The lifespan of the nourishments increased with increasing grainsize;

- The lifespan of the nourishments increased with increasing placement depth;

- The lifespan of the nourishments increased with increasing bar cycle period (the time it takes for an offshore moving bar to reach the position of the preceding bar);

- A more landward position of the nourishment reduced dune erosion during storms;

- A small fraction (less than 10%) of the nourished sand was lost offshore;

- The nourished sandbar developed a trough at the shoreward flank;

- The bar shoreward of the nourished bar migrated onshore;

- Part of the nourished sand was distributed alongshore to neighbouring coastal stretches;

- The feeder effect of the nourishments (sand supply from the nourishment to the beach) did not reach the supratidal beach;

- Accretion of the supratidal beach occurred in some cases by the leeside effect of the nourishments – the convergence of longshore sediment transport at the nourishment site due to local reduction of wave heights, with downdrift erosion as a consequence.

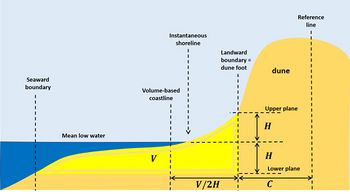

Design rules shoreface nourishments[9]

Shoreface nourishments are applied where longshore sandbars are present on the shoreface. The preferred nourishment location is at the seaward side of the outer sandbar (Fig. 2). The average volume of shoreface nourishments is 400-500 m3/m, similar to the volume of the outer bar; the average length is 4 km. This not only stops seaward bar migration, but may even initiate a landward migration of the inner sandbars (Fig. 3). The result is an increase of the sand volume of the subtidal and intertidal beach and a corresponding seaward advance of the coastline (the Dutch definition of shoreline position is related to the supratidal, intertidal and subtidal beach volume, see Fig. 4). Shoreface nourishments are generally most effective in terms of feeding the subtidal beach when their crest is at approximately NAP -5 m. It takes a few years before a shoreface nourishment has an effect on the shoreline position. Shoreface nourishments have an average lifespan of 4–10 years, which is the time that the shoreline resumes its pre-nourishment position.

Related articles

- Shore nourishment

- Beach nourishment

- Shoreface profile

- Nearshore sandbars

- Rip current

- Dealing with coastal erosion

- Ecological impacts of seabed sand mining

- Coastal Hydrodynamics And Transport Processes

- Experiences with beach nourishments in Portugal

References

- ↑ Grasmeijer, B., Huisman, B., Luijendijk, A., Schrijvershof, R., van der Werf, J., Zijl, F., de Looff, H. and de Vries, W. 2022. Modelling of annual sand transports at the Dutch lower shoreface. Ocean and Coastal Management 217, 105984

- ↑ Anthony, E.J. and Aagaard, T. 2020. The lower shoreface: Morphodynamics and sediment connectivity with the upper shoreface and beach. Earth-Science Reviews 210, 103334

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 van der Werf, J.J., Huisman, B.J.A., Price, T.D., Larsen, B.E., de Schipper, M.A., McFall, B.C., Krafft, D.R., Lodder, Q.J. and Ruessink, B.G. 2025. Shoreface nourishments: Research advances and future perspectives. Earth-Science Reviews 267, 105138

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Huisman, B.J.A., Walstra, D.J.R., Radermacher, M., De Schipper, M.A. and Ruessink, B.G. 2019. Observations and modelling of shoreface nourishment behaviour. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 7, 59

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Van der Spek, A.F.J. and Elias, E., 2013. The effects of nourishments on autonomous coastal behaviour. Procs. Coastal Dynamics Conf. 2013, pp. 1753-1762

- ↑ Ojeda E., Ruessink, B.G. and Guillen, J. 2008. Morphodynamic response of a two-barred beach to a shoreface nourishment. Coastal Engineering 55: 1185-1196

- ↑ Gijsman, R., Visscher, J. and Schlurmann, T. 2019. The lifetime of shoreface nourishments in fields with nearshore sandbar migration. Coastal Engineering 152, 103521

- ↑ Atkinson, A.L. and Baldock, T.E. 2020. Laboratory investigation of nourishment options to mitigate sea level rise induced erosion. Coastal Engineering 161, 103769

- ↑ Brand, E., Ramaekers, G. and Lodder, Q. 2022. Dutch experience with sand nourishments for dynamic coastline conservation – An operational overview. Ocean and Coastal Management 217, 106008

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|