Difference between revisions of "Impacts caused by increasing urbanization"

Margaretha (talk | contribs) m |

Margaretha (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

| − | {| border=" | + | {| border="2" Box 1: cellpadding="2" width="600pt" align="center"; |

||''' ''Perequazione Urbanistica'' in Italy''' | ||''' ''Perequazione Urbanistica'' in Italy''' | ||

Revision as of 14:53, 11 January 2008

|

Waiting for author to confirm changes

It is widely acknowledged that the coastal zones of the Mediterranean are coming under increasing pressure, which in turn is having serious implications for the environment and for the sustainable use of these highly valued ecosystems. One of the major pressures in the Mediterranean results from increasing urbanization of coastal areas. This article illustrates the entity of the phenomena and of values interested by the increasing urbanization of Mediterranean coastal zones.

Urbanization of costal zones in the Mediterranean

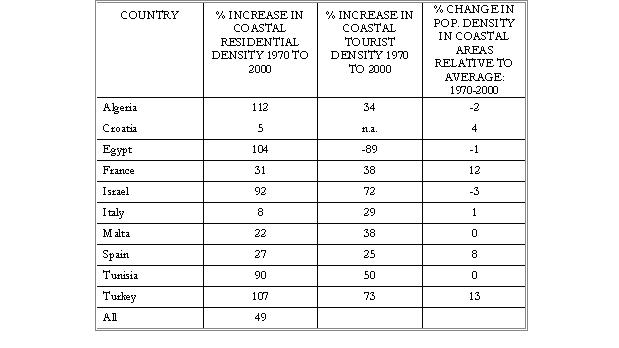

All the littoral states have undertaken some measures to try and protect their coastal zones from overdevelopment, or development that is socially and environmentally damaging. The success of these measures however, is questionable. In spite of well-reasoned and carefully drafted regulations, the pressure has continued to increase. The laws are often ignored by developers who put up illegal units. In this and other ways the regulations are ineffective in achieving the key goals of sustainable development: i.e. development that protects the environment for present and future generations to enjoy. There is ample documented evidence that the human pressure on coastal resources is increasing. Table 1 gives some basic data for the countries covered in this study. In the 30 years to 2000 densities in coastal areas increased by 49 percent, ranging from a low of 5 percent in Croatia, to a high of 112 percent in Algeria . The same period has also seen substantial increases in tourist densities in all countries except Egypt. Values for the others range from 25 percent in Spain to 73 percent in Turkey. In general the North African countries with the fast growing populations are also the ones with the highest rates of growth of coastal densities, including tourism densities (Algeria, Tunisia and Turkey). We also observe some shift in the relative densities of the population between the coastal zones and the national average. The last column of Table 1 gives the percentage change in this ratio between 1970 and 2000. It shows a relative movement outward for Croatia, France, Italy, Spain and Turkey. In Algeria, Egypt and Israel the density has increased slightly faster on average than it has in the coastal zones.

Table 1: Indicators of Coastal Zone Pressure in the Mediterranean

Source: Plan Bleu, 1989 [1], 2005 [2], Attané and Courbage, 2001. [3]

In view of these strong human pressures on coastal zones, it is clear that increased regulations may be warranted to protect the resources (see Fig. 1).

Any policy of coastal zone protection and land use planning would benefit from a better idea of the benefits and costs associated with different patterns of land use. Increasing urbanization of the coasts creates benefits for some individuals living next to the sea. Yet the same actions are causing external costs in the form of reduced visual benefits and reduced access to others who enjoyed these environmental services before. Some research has been executed that has estimated Values of amenities in coastal zones in order to determine such benefits and costs.

Recommendations for Regulation

The pressure on coastal resources from ‘artificialization’ or conversion of natural habitats into man-made ones is growing. This pressure has been increasing steadily, at least since 1970 and probably from before then. Even since the 1990s when the problem has been recognized and attention devoted to tackling it, the rate of urban development along the coasts has continued to increase in most countries. The integrated coastal zone management is rarely effective in its implementation. Legislation is now in place in several countries that aims to provide the right regulatory framework, but it is being hampered by a lack of coordination between the regulating authorities (e.g. those responsible for land and sea and those responsible for different levels of government). The presence of specific coastal legislation does not appear to guarantee a better performance in terms of coastal protection. Lack of compliance is a problem, although the full extent of it is not known, except for a few countries. Illegal construction is a frequent phenomenon and is encouraged by modest fines, the granting of amnesties for dwellings that have been in place for a number of years and the practice of applying a statute of limitations on legal proceedings against violators. It is not possible from the data available to establish how effective the different instruments such as setback policies and other regulations have been in protecting coastal zones. A detailed assessment of the extent of violation of the setback rule therefore is needed. But even that would provide only a fraction of the information that should be collected. With a small setback area, at most a few hundred meters, a policy of intense development close to the sea is feasible and can result in a coastal zone that is substantially developed. Thus a wider assessment of the effectiveness of regulations by measuring outcomes is required. Some limited evidence that is presented is not encouraging – it does indicate continued and increasing pressure on coastal natural resources. The experience so far indicates that a stricter regime is needed to protect overdevelopment of coastal resources. The practice of amnesties for illegal construction must stop and illegal units should be more frequently subject to demolition. The use of normal planning regulations for land use needs to be buttressed by special conditions that apply to littoral zones that extend beyond the common range of 100-200 metres. In these zones construction should be completely banned. A second zone, perhaps up to one or even two kilometres, should be subject to special permission from an authority that is responsible of integrated coastal zone management and that supersedes other planning authorities. Decisions on permitting development in this zone should be part of a strategic plan. One possible regulatory tool could be the use of transferable development rights. An authority that restricted development in one area would compensate those who lost value as a result of such a restriction by allocating rights in other areas. Such systems have been an effective planning tool in municipalities and districts in the US and elsewhere. Alternatively authorities that were given coastal development rights could share the benefits with those where the rights were denied. Such a system applies in Italy (the so-called ‘perequazione urbanistica’). The system has allowed areas to be protected by arranging the transfer of benefits from other areas from as long ago as the early 1980s (see Box).

| Perequazione Urbanistica in Italy

The idea behind the Perequazione Urbanistica is to share the benefits and costs of changes in land use status across communities and individuals. So, if one community or person is given the rights to develop land from agricultural or recreational use to use for dwellings, and another community is restricted not to develop land in this way, the two communities may share the benefits from the increased development. The scheme works by allocating to all residents in a given area the right to develop a part of their land. Then planning laws are introduced which in effect prohibit the exercise of this right in some places. These laws also define certain areas of land for public use – roads, parks etc. Those who cannot exercise their right by virtue of the planning regulations can sell these rights to others so that they can develop more of their land than their right allocation allows. Where the state needs to acquire land for public use, it does so at the agricultural value of that land, but this still allows the owner to sell the rights to development to another person who needs more than he or she has. In this way no one suffers from a planning restriction. The scheme has been applied in Italy specially to acquire land for public services with resorting to compulsory purchase under an Eminent Domain law or its equivalent. But it has also been applied to ecologically oriented uses. An example is the case of Cantù (near Como) where it has been used to preserve some Greenfield areas. Another is the case of Chiavari (near Genoa) where further development of the hills above the resort town have been deprived of development rights but these can be exercised elsewhere. |

Another important instrument that can protect coastal development is land taxation. It may be possible to tax increased land values when development rights are accorded for coastal areas and use the revenues for the protection of other areas, including transfers to these areas to make up for restricting development. This serves a similar purpose as the perequazione urbanistica in Italy, except it uses a tax instrument. In general the authorities should seek to use fiscal instruments such as the above where possible. Given the difficulties in policing development, and the very strong incentives that individuals have to break the law by undertaking building in violation of planning regulations, it makes it much easier for the authorities to achieve their goals if costs of conservation are shared equitably. That said, some degree of protection of the coasts will always be needed. This can only be achieved if the political will is there. In any plan for coastal protection there will be positive and negative externalities to account for. The data available are limited and more needs to be collected on the value of beaches with and without development, the value of coastal landscapes without development and with different types of development, the costs of limited access to beaches and the ways in which beach users respond to increased development. However, the evidence is strongly in favour of conservation for plausible cases. The benefits to owners and developers of beachfront developments are often smaller than the plausible losses to beach users. Taking account of important non-use values will make the case for conservation even stronger. Finally we note that the losses are much greater from ribbon development than for cluster development. However all these results need to be strengthened with further research.

References

- ↑ Plan Bleu (1989): Futures for the Mediterranean Basin. The Blue Plan. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Plan Bleu (2005): A Sustainable Future for the Mediterranean: The Blue Plan’s Environment and Development Outlook. Earthscan: London.

- ↑ Attané I., Courbage Y. (2001) “ La démographie en Méditerranée – Situation et Projections.” Les Fascicules du Plan Bleu 11, Economica, 249 p.

Literature and further reading

General

EEA (2006): The changing faces of Europe's coastal areas, relazione AEA n. 6/2006, Agenzia Europea Per l'Ambiente Copenhagen.

Valuation of Coastal Landscape

Abelson, P. and A. Markandya. (1985) "The Interpretation of Capitalised Hedonic Prices in a Dynamic Environment", Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 12, 195 206.

Arriaza, M., J.F Cañas-Ortega, J.A Cañas-Madueño, P. Ruiz-Aviles (2004) “Assessing the Visual Quality of Rural Landscapes.” Landscape and Urban Planning 69 115-125

Bell, F.W and V R Leeworthy, (1990) “Recreational demand by tourists for saltwater beach days”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 18(3) 189-205.

Benson, E.D, J.L Hansen, A.L Schwartz Jr. and G.T Smersh (1998) “Pricing Residential Amenities: The Value of a View.” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 16(1) 55-73

Bond, M.T, V.L Seiler and M.J Seiler (2002) “Residential Real Estate Prices: A Room with a View”. Journal of Real Estate Research 23(1/2) 129-137

Dramstad, W.E, G. Fry, W.J Fjellstad., B. Skar, W. Hellisksen., M-L.B Sollund, M.S Tveit, A.K Geelmuden and E Framstad (2001) “Integrating Landscape-Based Values – Norwegian Monitoring of Agricultural Landscapes.” Landscape and Urban Planning 57 257-268

Ergin, A., A.T. Williams and A. Metcalf (2006) “Coastal Scenery : Appreciation and Evaluaton” Journal of Coastal Research, 22, 958-964.

Fraser, R. and G. Spencer (1998) “The Value of an Ocean View: an Example of Hedonic Property Amenity Valuation.” Australian Geographical Studies 36(1) 94-86

Landry, C. E. and K. E. McConnell, (2004) "Hedonic Onsite Model of Recreation Demand", Paper presented at the Southern Economics Association 74th Annual Conference, New Orleans, LA 2004.

Leeworthy, V.R and N.F Meade (1989-1990) A Socioeconomic Pro,le of Recreationists at Public Outdoor Recreation Sites in Coastal Areas: Vols. 1-5, Public Area Recreation Visitors Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, US Department of Commerce, Rockville, MD.

Luttik, J. (2000) “The Value of Trees, Water and Open Space as Reflected By House Prices in the Netherlands” Landscape and Urban Planning 48 161-167.

Marzetti Dell’Aste Brandolini, S. (2003) Economic Valuation of the Recreational Beach Use: The Italian Case-Studies of Lido Di Dante, Trieste, Ostia and Pellestrina Island. Final Report for the DELOS project. Available online at http://www.delos.unibo.it/Docs/Deliverables/D28A.pdf. (19/1/06)

Milton, J., J. Gressel and D. Mulkey (1984) “Hedonic Amenity Valuation and Functional Form Specification” Land Economics 60(4) 378-387

Morgan, R. and A.T. Williams (1998) “Video Panorama Assessment of Beach Landscape Aesthetics on the Coast of Wales”, Journal of Coastal Conservation, 5 (1), 13-22.

Muriel, T., Abdelhak, N., Gildas, A., and F. Bonnieux (2006) “Evaluation des bénéfices environnementaux par la méthode des prix hédonistes: une application au cas du littoral”. Paper presented at Les 1ères Rencontres du Logement de L'IDEP Marseille 19-20 October 2006. Available online at www.vcharite.univ-mrs.fr/idep/secteurs/logement/rencontres/document/papier/Travers.pdf

Parsons, G.R. and Y. Wu (1991) "The Opportunity Cost of Coastal Land Use Controls: An Empirical Analysis" Land Economics 67(3) 308-316

Penning-Rowsell, E.C, C.H Green, P.M Thompson, A.M Coker, S.M Tunstall, C. Richards and D.J Parker, (1992) The Economics of Coastal Management, Belhaven Press, London, 380pp.

Polomé, P., S. Marzetti and A. van der Veen (2005) “Economic and Social Demands For Coastal Protection” Coastal Engineering 52 819-840.

Silberman, J. and M. Klock, (1988) “The recreation benefits of beach nourishment”, Ocean and Shoreline Management, 11 73-90

Sohngen, B., F.Lichtkoppler and M. Bielen, (1999)"The Value of Lake Erie Beaches", FS-078 Ohio State University

Tudorf, D.T. and A.T. Williams (2003) “Public perception and Opinion of Visible Beach Aesthetic Pollution: The Utilisation of Photography” Journal of Coastal Research, 19, 1104-1115.

Whitmarsh, D., J. Northen and S. Jaffry (1999) Recreational benefits of coastal protection: a case study Marine Policy 23(4) 453-464

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|