Difference between revisions of "Setting the Direction in ICZM"

m (Daphnisd moved page Setting the Direction to Setting the Direction in ICZM) |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

Many objectives will be predetermined in the existing international, national and sub-national policies. Examples include, above all, the Barcelona Convention, but also the instruments such as Horizon 2020, the Water Framework Directive, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, the Maritime Policy and other. In many cases these adequate benchmarks will be provided, but they should be reviewed to identify the potential to exceed them as a minimum aspiration. | Many objectives will be predetermined in the existing international, national and sub-national policies. Examples include, above all, the Barcelona Convention, but also the instruments such as Horizon 2020, the Water Framework Directive, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, the Maritime Policy and other. In many cases these adequate benchmarks will be provided, but they should be reviewed to identify the potential to exceed them as a minimum aspiration. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See Also== | ||

| + | * [[CC_ICZM_Process/Setting_the_vision#Setting_the_direction|Setting the direction in a ICZM planning process for Climate Change]] | ||

{{RetoICZMsevi}} | {{RetoICZMsevi}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Scenarios are “sets of plausible stories, supported with data and simulations, about how the future might unfold from current conditions under alternative human choices” (Polasky et al., 2011 | ||

| + | <ref name=P>Polasky, S., Carpenter, S., Folke, C., et al. (2011): Decision-making under great uncertainty: environmental management in an era of global change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 26: 398-404.</ref>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | == What are scenarios? == | ||

| + | Scenarios have become important management and policy support tools. Broadly their purpose is to allow decision makers to think through the implications of different assumptions about the ways [[Ecosystem|ecosystems]] might respond to different drivers of change (Ash et al., 2011<ref>Ash, N, Blanco, H., Brown, C., Garcia, K., Henrichs, T., Lucas, N., Raudsepp-Hearne, C., David Simpson, R., Scholes, R., Tomich, T.P., Vira, B. and M. Zurek (Eds). (2010): Ecosystems and human well-being: a manual for assessment practitioners. Island Press</ref>; Alcamo, 2010<ref>Alcamo, J. (2001): Scenarios as tools for international environmental assessments. European Environment Agency, 1-31</ref>). This is of course a difficult task because in practice it is very hard to make predictions about the future for anything other than simple, well behaved systems. Scenario thinking is therefore intended to help us cope with more complex situations involving a high degree of uncertainty (EEA, 2007<ref>EEA (2007) Pan-European Environment: Glimpses into an Uncertain Future, EEA Report 2007-4</ref>) (Figure 1). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Dealing with complexity and uncertainity, and the role of scenarios.PNG|600px|thumbnail|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | As this figure suggests they sit in the ‘middle ground’ between ‘hard facts’ and robust predictions, on the one hand, and mere speculation on the other. Polasky et al. (2011<ref name=P/>) have suggested that one way to think about scenario methods is that they provide us with tools to help us think creatively about the future. Many other commentators have made a similar point and suggested that in this context we must accept that there is no one way in which they might be used. Zurek and Henrichs (2007<ref>Zurek, M. and T. Henrichs (2007): Linking scenarios across geographical scales in international environmental assessments. Technological Forecasting and Social Change</ref>) for example, have argued that scenarios can be employed to: | ||

| + | * Help structure choices that we need to make by revealing their possible long‐term consequences. | ||

| + | * Support strategic planning and decision‐making by providing a platform for thinking through the implications of various options in the face of future uncertainties. | ||

| + | * Helping to facilitate stakeholder participation in the strategic development process — by allowing them to voice of conflicting opinions and world views. | ||

| + | There are many examples of the use of scenarios. Some of the most widely discussed are those dealing with future climate change. The Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), for example, developed six potential futures, based on different assumptions about economic growth, population change, technological change, and cultural and social factors (Nakicenovic et al., 2000<ref>Nakicenovic, N. et al. (2000): Special Report on Emissions Scenarios: A Special Report of Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press</ref>) (Figure 2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:The IPCC SRES Scenarios.PNG|600px|thumbnail|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other notable studies include the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005<ref>MA Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005): Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington, DC http://www.millenniumassessment.org Millennium Ecosystem Assessment</ref>). The latter developed four scenarios describing alternative, global ecosystem futures based on different approaches to managing ecosystem services (proactive vs reactive) at different spatial scales (global vs regional). The scenarios made very different projections for human well‐being as it relates to ecosystem services in developed and developing societies (Figure 3). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:The MA scenaios.PNG|600px|thumbnail|center]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Current Approaches to Developing Scenarios == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although scenario methods have been widely applied, their use and in particular how we might evaluate their effectiveness is still being actively discussed. On balance, the literature suggests that there is no single approach that is acceptable to all situations. This has come about because as Bradfield et al. (2005<ref>Bradfield, R., Wright, G., Burt, G., Cairns, G. and M. van der Heijden (2005): The origins and evolution of scenario techniques in long range business planning. Futures, 37, 795-812</ref>) observe, many different terms have been used in association with the scenario concept, such as ‘planning’, ‘thinking’, ‘forecasting’, ‘analysis’ and ‘learning’ are all of which variously used in describing the different motives for using scenario tools. The tension between the ‘forecasting’ and ‘learning’ perspectives is particularly important to consider, and it is one that has recurred throughout the discussions about the way scenarios might be used in PEGASO. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When scenarios are used to make forecasts, or projections about the future, the work generally represents scenarios as distinct ’products’. Thus for Polasky et al. (2011<ref name=P/>) scenarios are essentially: “sets of plausible stories, supported with data and simulations, about how the future might unfold from current conditions under alternative human choices”. This kind of application is illustrated by the SRES and MA studies described above. In these studies the scenarios are ‘products’ in that they are well defined, general in character and capable of being taken by others and applied in different situations. Looked at in this way, scenarios are essentially quantitative or qualitative modelling exercises. Although this is a legitimate use of scenarios, other commentators have argued that scenario building can be valuable in other ways. Most importantly they suggest it can be used to facilitate social learning. | ||

| + | |||

| + | O'Neill et al. (2008<ref>O'Neill, B., Pulver, S., VanDeveer, S. and Y. Garb (2008): Where next with global environmental scenarios? Environmental Research Letters 3: 1-4</ref>) have described what they see as a ‘process-perspective’ on scenarios, which emphasises the importance of them as a way of encouraging social learning within and between diverse groups. The scenario building exercise can, they suggest, help to find synergies between different viewpoints, of consensus building, and of developing shared responsibilities for problem solving. From this perspective, the scenarios products themselves are perhaps less important than the dialogue generated in their production, and the legacy that those dialogues leave. Looked at in this way, scenarios are firmly part of capacity building and training, and have strong links to the use of participatory processes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Taking Scenarios forward in PEGASO == | ||

| + | |||

| + | In looking to the way scenarios might be used in PEGASO, it is important to note that there is no single ‘right way’ but that a different approach might be appropriate in different situations. Thus it is apparent that there are many global or regional studies that have already developed scenarios that should be discussed and updated and even extended within PEGASO. One such study is Plan Bleu’s Sustainable Development Outlook for the Mediterranean (2005<ref>[https://planbleu.org/en/publications/the-blue-plans-sustainable-development-outlook-for-the-mediterranean/ Plan Bleu’s Sustainable Development Outlook for the Mediterranean:] A Practitioners guide to Imagine: The systematic and prospective sustainability analysis.</ref>), which has attempted to look at development frameworks through to 2025. Another example is the set of scenarios for the Black Sea, developed by the EnviroGRIDS project (2012<ref>[http://www.envirogrids.net/ Envirogrids Project]</ref>). As part of the scenario work in PEGASO we will be looking at these and other scenario studies and making a review of their relevance and implications in the content of ICZM issues in the Mediterranean and Black Sea Basins. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The review of existing scenario studies and their development for helping us to understand [[ICZM]] issues could be part of the PEGASO Platform, and used by people and organisations to stimulate debate about future management and policy options. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition, so as to support the work on participatory methods within PEGASO, more interactive scenario tools will be looked at. These include the participatory methods developed in Plan Bleu’s Imagine initiative. Imagine allows us to work with stakeholders at more local scales to explore questions about desired futures by using indicators and discussing limits of acceptable change. We will also be looking at how Bayesian Belief networks can be used to construct scenarios using participatory methods. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For more information, read the [[media:WP4 Factsheet 4.3 updated July2013.pdf|factsheet]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{UNOTT}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == References == | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Further Reading== | ||

| + | Pinnegar, J., Viner, D., Hadley, D., Dye, S., Harris, M., and F. Simpson (2006): Alternative future scenarios for marine ecosystems. 1-112. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:ICZM methodology (PEGASO)]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:54, 25 July 2020

Setting the Direction, or preparing the Vision, will define the desired or intended future state of the coastal area in terms of its fundamental strategic direction. The vision describes in simple terms the condition of the coastal area in the future, in a time-span of 10 to 30 years and even beyond, if the strategy, plan or programme is implemented successfully. Ideally the vision should be:

- Clear and compelling;

- Aligned with the partners’ and the community’s aspirations and existing policies;

- Ambitious and memorable;

- A vivid picture of a desired future.

The Vision and the objectives are derived from the agreed priorities. PAP/RAC has defined a "model" vision for the Mediterranean coast, which encompasses 6 principles of sustainable development. It envisions coast that is:

Resilient - resilient to future uncertainties of climate change, including rising sea levels, warming and drought; resilient to climate variability such as extreme storms, floods, waves, etc; resilient to earthquakes and erosion; resilient to negative impacts of human processes, including the pressure of tourism and urban development on the coast.

Productive - productive financially in traditional, modern and future economic sectors; supporting the economic aspirations of the coastal community; providing a competitive asset to the local economy, high in natural and economic values - increasing GDP and alleviating poverty.

Diverse - ecologically diverse: a rich mosaic of marine and terrestrial ecosystems; diverse rural and urban landscapes, old and new; a diverse economy - providing a diverse, but distinctly Mediterranean experience; a diverse society – providing conditions for a rich mixture of social groups, open to the outside world, etc.

Distinctive - retaining the cultural distinctiveness of coastal areas, including their architecture, customs and landscapes, recognising the Mediterranean as the “cradle of civilisation” - providing a distinctive marketing image on which to attract investment.

Attractive - retaining the attractiveness of the coast, not only to visitors but also to investors and local people to promote a self-sustaining cycle of sustainable growth.

Healthy - free from pollution from land and marine-based sources, with clean fresh and marine waters and the air - providing a healthy environment for people, natural resources such as fisheries, and wildlife.

Objectives of the Vision will describe how the implementation of the Vision can be measured and achieved, and will reflect the governance, environmental and socio-economic priorities. Objectives describe, in measurable terms, the desired end state and are the measure of the ICZM Process performance.

The objectives should be measurable, attainable, realistic and time-targeted. Beyond this simple description, however, the objectives can become more complex, distinguishing between: High Level Objectives (or Goals) and clusters of Sub-Objectives.

Many objectives will be predetermined in the existing international, national and sub-national policies. Examples include, above all, the Barcelona Convention, but also the instruments such as Horizon 2020, the Water Framework Directive, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, the Maritime Policy and other. In many cases these adequate benchmarks will be provided, but they should be reviewed to identify the potential to exceed them as a minimum aspiration.

Contents

See Also

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|

Return to: Setting the vision

Scenarios are “sets of plausible stories, supported with data and simulations, about how the future might unfold from current conditions under alternative human choices” (Polasky et al., 2011 [1]).

What are scenarios?

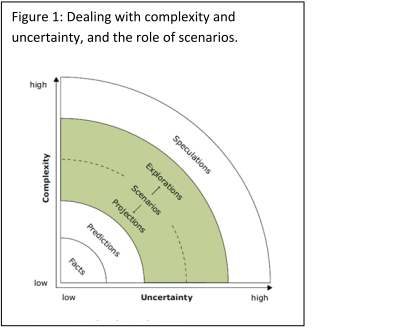

Scenarios have become important management and policy support tools. Broadly their purpose is to allow decision makers to think through the implications of different assumptions about the ways ecosystems might respond to different drivers of change (Ash et al., 2011[2]; Alcamo, 2010[3]). This is of course a difficult task because in practice it is very hard to make predictions about the future for anything other than simple, well behaved systems. Scenario thinking is therefore intended to help us cope with more complex situations involving a high degree of uncertainty (EEA, 2007[4]) (Figure 1).

As this figure suggests they sit in the ‘middle ground’ between ‘hard facts’ and robust predictions, on the one hand, and mere speculation on the other. Polasky et al. (2011[1]) have suggested that one way to think about scenario methods is that they provide us with tools to help us think creatively about the future. Many other commentators have made a similar point and suggested that in this context we must accept that there is no one way in which they might be used. Zurek and Henrichs (2007[5]) for example, have argued that scenarios can be employed to:

- Help structure choices that we need to make by revealing their possible long‐term consequences.

- Support strategic planning and decision‐making by providing a platform for thinking through the implications of various options in the face of future uncertainties.

- Helping to facilitate stakeholder participation in the strategic development process — by allowing them to voice of conflicting opinions and world views.

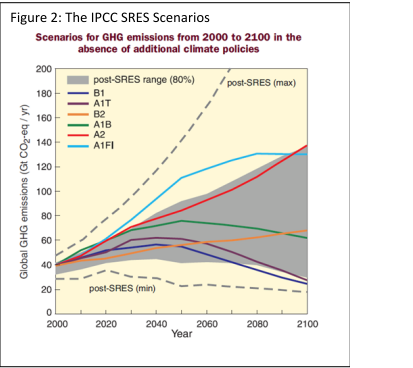

There are many examples of the use of scenarios. Some of the most widely discussed are those dealing with future climate change. The Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), for example, developed six potential futures, based on different assumptions about economic growth, population change, technological change, and cultural and social factors (Nakicenovic et al., 2000[6]) (Figure 2).

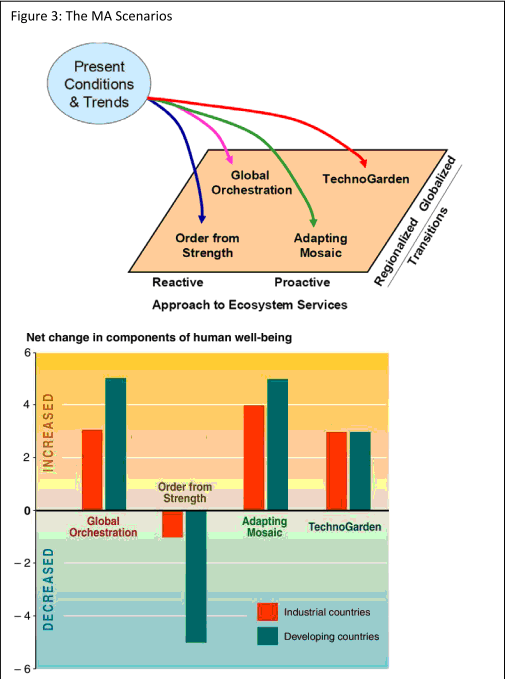

Other notable studies include the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005[7]). The latter developed four scenarios describing alternative, global ecosystem futures based on different approaches to managing ecosystem services (proactive vs reactive) at different spatial scales (global vs regional). The scenarios made very different projections for human well‐being as it relates to ecosystem services in developed and developing societies (Figure 3).

Current Approaches to Developing Scenarios

Although scenario methods have been widely applied, their use and in particular how we might evaluate their effectiveness is still being actively discussed. On balance, the literature suggests that there is no single approach that is acceptable to all situations. This has come about because as Bradfield et al. (2005[8]) observe, many different terms have been used in association with the scenario concept, such as ‘planning’, ‘thinking’, ‘forecasting’, ‘analysis’ and ‘learning’ are all of which variously used in describing the different motives for using scenario tools. The tension between the ‘forecasting’ and ‘learning’ perspectives is particularly important to consider, and it is one that has recurred throughout the discussions about the way scenarios might be used in PEGASO.

When scenarios are used to make forecasts, or projections about the future, the work generally represents scenarios as distinct ’products’. Thus for Polasky et al. (2011[1]) scenarios are essentially: “sets of plausible stories, supported with data and simulations, about how the future might unfold from current conditions under alternative human choices”. This kind of application is illustrated by the SRES and MA studies described above. In these studies the scenarios are ‘products’ in that they are well defined, general in character and capable of being taken by others and applied in different situations. Looked at in this way, scenarios are essentially quantitative or qualitative modelling exercises. Although this is a legitimate use of scenarios, other commentators have argued that scenario building can be valuable in other ways. Most importantly they suggest it can be used to facilitate social learning.

O'Neill et al. (2008[9]) have described what they see as a ‘process-perspective’ on scenarios, which emphasises the importance of them as a way of encouraging social learning within and between diverse groups. The scenario building exercise can, they suggest, help to find synergies between different viewpoints, of consensus building, and of developing shared responsibilities for problem solving. From this perspective, the scenarios products themselves are perhaps less important than the dialogue generated in their production, and the legacy that those dialogues leave. Looked at in this way, scenarios are firmly part of capacity building and training, and have strong links to the use of participatory processes.

Taking Scenarios forward in PEGASO

In looking to the way scenarios might be used in PEGASO, it is important to note that there is no single ‘right way’ but that a different approach might be appropriate in different situations. Thus it is apparent that there are many global or regional studies that have already developed scenarios that should be discussed and updated and even extended within PEGASO. One such study is Plan Bleu’s Sustainable Development Outlook for the Mediterranean (2005[10]), which has attempted to look at development frameworks through to 2025. Another example is the set of scenarios for the Black Sea, developed by the EnviroGRIDS project (2012[11]). As part of the scenario work in PEGASO we will be looking at these and other scenario studies and making a review of their relevance and implications in the content of ICZM issues in the Mediterranean and Black Sea Basins.

The review of existing scenario studies and their development for helping us to understand ICZM issues could be part of the PEGASO Platform, and used by people and organisations to stimulate debate about future management and policy options.

In addition, so as to support the work on participatory methods within PEGASO, more interactive scenario tools will be looked at. These include the participatory methods developed in Plan Bleu’s Imagine initiative. Imagine allows us to work with stakeholders at more local scales to explore questions about desired futures by using indicators and discussing limits of acceptable change. We will also be looking at how Bayesian Belief networks can be used to construct scenarios using participatory methods.

For more information, read the factsheet

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Polasky, S., Carpenter, S., Folke, C., et al. (2011): Decision-making under great uncertainty: environmental management in an era of global change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 26: 398-404.

- ↑ Ash, N, Blanco, H., Brown, C., Garcia, K., Henrichs, T., Lucas, N., Raudsepp-Hearne, C., David Simpson, R., Scholes, R., Tomich, T.P., Vira, B. and M. Zurek (Eds). (2010): Ecosystems and human well-being: a manual for assessment practitioners. Island Press

- ↑ Alcamo, J. (2001): Scenarios as tools for international environmental assessments. European Environment Agency, 1-31

- ↑ EEA (2007) Pan-European Environment: Glimpses into an Uncertain Future, EEA Report 2007-4

- ↑ Zurek, M. and T. Henrichs (2007): Linking scenarios across geographical scales in international environmental assessments. Technological Forecasting and Social Change

- ↑ Nakicenovic, N. et al. (2000): Special Report on Emissions Scenarios: A Special Report of Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ MA Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005): Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington, DC http://www.millenniumassessment.org Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

- ↑ Bradfield, R., Wright, G., Burt, G., Cairns, G. and M. van der Heijden (2005): The origins and evolution of scenario techniques in long range business planning. Futures, 37, 795-812

- ↑ O'Neill, B., Pulver, S., VanDeveer, S. and Y. Garb (2008): Where next with global environmental scenarios? Environmental Research Letters 3: 1-4

- ↑ Plan Bleu’s Sustainable Development Outlook for the Mediterranean: A Practitioners guide to Imagine: The systematic and prospective sustainability analysis.

- ↑ Envirogrids Project

Further Reading

Pinnegar, J., Viner, D., Hadley, D., Dye, S., Harris, M., and F. Simpson (2006): Alternative future scenarios for marine ecosystems. 1-112.