Difference between revisions of "Waves"

(→Wave climate classification according to wind climate) |

|||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

====[[Statistical description of wave parameters]]==== | ====[[Statistical description of wave parameters]]==== | ||

| − | ==== | + | ====Wave climate classification according to wind climate==== |

The different wind climates, which dominate different oceans and regions, cause correspondingly characteristic wave climates. These characteristic wave climates can be classified as follows: | The different wind climates, which dominate different oceans and regions, cause correspondingly characteristic wave climates. These characteristic wave climates can be classified as follows: | ||

| + | *Storm wave climate. | ||

| + | *Swell climate. | ||

| + | *Monsoon wave climate. | ||

| + | *Tropical cyclone climate. | ||

| − | + | For details on these calssifications follow the link [[Wave climate classification according to wind climate]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Long Waves=== | ===Long Waves=== | ||

Revision as of 15:48, 22 January 2007

Contents

Waves

There is typically a distinction between short waves, which are waves with periods less than approximately 20 s, and long waves or long period oscillations, which are oscillations with periods between 20-30 s and 40 min. Water-level oscillations with periods or recurrence intervals larger than around 1 hour, such as astronomical tide and storm surge, are referred to as water-level variations. The short waves are wind waves and swell, whereas long waves are divided into surf-beats, harbour resonance, seiche and tsunamis.

Natural waves can be viewed as a wave field consisting of a large number of single wave components each characterised by a wave height, a wave period and a propagation direction. Wave fields with many different wave periods and heights are called irregular, and wave fields with many wave directions are called directional. A wave field can be more or less irregular and more or less directional.

Short Waves

Types of waves

The short waves are the single most important parameter in coastal morphology. Wave conditions vary considerably from site to site, depending mainly on the wind climate and on the type of water area. The short waves are divided into:

- Wind waves, also called storm waves, or sea. These are waves generated and influenced by the local wind field. Wind waves are normally relatively steep (high and short) and are often both irregular and directional, for which reason it is difficult to distinguish defined wave fronts. The waves are also referred to as short-crested. Wind waves tend to be destructive for the coastal profile because they generate an offshore (as opposed to onshore) movement of sediments, which results in a generally flat shoreface and a steep foreshore.

- Swell are waves, which have been generated by wind fields far away and have travelled long distances over deep water away from the wind field, which generated the waves. Their direction of propagation is thus not necessarily the same as the local wind direction. Swell waves are often relatively long, of moderate height, regular and unidirectional. Swell waves tend to build up the coastal profile to a steep shoreface.

Fig 5.1 Irregular directional storm waves (including white-capping) and regular unidirectional swell.

Wave generation

Wind waves are generated as a result of the action of the wind on the surface of the water. The wave height, wave period, propagation direction and duration of the wave field at a certain location depend on:

- The wind field (speed, direction and duration)

- The fetch of the wind field (meteorological fetch) or the water area (geographical fetch)

- The water depth over the wave generation area.

Swell is, as previously stated, wind waves generated elsewhere but transformed as they propagate away from the generation area. The dissipation processes, such as wave-breaking, attenuate the short period much more than the long period components. This process acts as a filter, whereby the resulting long-crested swell will consist of relatively long waves with moderate wave height.

Wave transformation

Statistical description of wave parameters

Wave climate classification according to wind climate

The different wind climates, which dominate different oceans and regions, cause correspondingly characteristic wave climates. These characteristic wave climates can be classified as follows:

- Storm wave climate.

- Swell climate.

- Monsoon wave climate.

- Tropical cyclone climate.

For details on these calssifications follow the link Wave climate classification according to wind climate.

Long Waves

The long waves are primarily second order phenomena of shallow water wave processes. The four main types of long waves are described in the following.

Surf beat

Natural waves often show a tendency to wave grouping, where a series of high waves follows a series of low waves. This is especially pronounced on open sea-coasts, where the incoming waves may be of different origins and will thus have a large spreading in wave heights, wave directions, and wave periods (or frequencies). Wave grouping will cause oscillations in the wave set-up with a period corresponding to approx. 6 – 8 times the mean wave period; this phenomenon is called surf-beats. Surf-beats near port entrances are very important in relation to mooring conditions in the port basins and sedimentation in the port entrance.

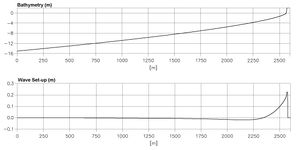

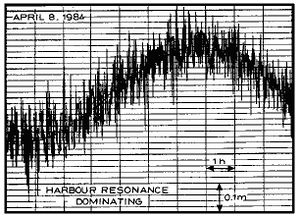

Fig 5.10

Wave set-up (upper), surf beat generated harbour resonance, recorded by a tide gauge, in a small port (middle) and circulation caused by the gradient in the wave set-up.

Harbour resonance

Harbour resonance is forced oscillation of a confined water body (e.g. a harbour basin or a lagoon) connected to a larger water body (the sea). If long-period oscillations are present in the sea, e.g. due to wave grouping or surf-beats or seiche, large oscillations at the natural frequency of the confined water body may occur. Oscillations at the first harmonic, which are the simplest mode of resonance, are often called the pumping or Helmholz mode.

Harbour resonance normally has periods in the range of 2 to 10 minutes. It is especially important in connection with the mooring conditions for large vessels, as their resonance period for the so-called surge motion is often close to that of the harbour resonance. In addition the associated water exchange may cause siltation.

Seiche

A seiche is the free oscillation of a water body, probably caused by rapid variations in the wind conditions. Seiche can occur in closed water areas, such as lakes or lagoons, and in semi-closed water bodies, such as bays. The period of the seiche oscillation is typically in the range of 2 to 40 minutes. Seiche can influence a port in the same manner as surf-beats. It is important to establish whether seiche is present in an area through field investigations, and if so, to take it into account in the layout of the port. Surf-beat influence within a port is often caused by an inexpedient layout. The influence of surf-beat is not applicable for seiche, as seiche is not limited to the nearshore zone. This means that if seiche motion is present in an area, it will inevitably penetrate the entrance. However, its impact on the port may be minimised through a proper layout.

Tsunami

A tsunami is a single wave, which is generated by sub-sea earthquakes; it typically has a period of 5 to 60 minutes. Tsunami waves can travel long distances across the oceans; they are similar to shallow water waves, which means that the speed v is calculated as the square root of the product of the water depth and the acceleration of gravity, v = (gh)1/2. Consequently, tsunamis travel very fast in the deep oceans. If the water depth is 5000 m, the speed will be more than 200 m/s or about 800 km/hour. A tsunami is normally not very high in deep water, but when it approaches the coastline, the wave will be shoaling and can reach a height of more than 10 m. Tsunamis are rare and coastal projects seldom take them into account. However, in very sensitive projects, such as nuclear power plants located in the coastal hinterland, the risk must be considered.

Currents

The various types of currents in the sea, which may be important to coastal processes in one way or another, are described in the following.

Currents in the Open Sea

Tidal currents are formed by the gravitational forces of the sun, the moon and the planets. These currents are of oscillatory nature with typical periods of around 12 or 24 hours, the so-called semi-diurnal and diurnal tidal currents. The tidal currents are strongest in large water depths away from the coastline and in straits where the current is forced into a narrow area. The most important tidal currents in relation to coastal morphology are the currents generated in tidal inlets. Typical maximum current speeds in tidal inlets are approx. 1 m/s, whereas tidal current speeds in straits and estuaries can reach speeds as high as approx. 3 m/s.

Fig 5.11

Tidal currents in tidal inlet (Caravelas in Brazil).

Wind-generated currents are caused by the direct action of the wind shear stress on the surface of the water. The wind-generated currents are normally located in the upper layer of the water body and are therefore not very important from a morphological point of view. In very shallow coastal waters and lagoons, the wind-generated current can, however, be of some importance. Wind-generated current speeds are typically less than 5 per cent of the wind speed.

Storm surge current is the current generated by the total effect of the wind shear stress and the barometric pressure gradients over the entire area of water affected by a specific storm. This type of current is similar to the tidal currents. The horizontal current velocity follows a logarithmic distribution in the water profile and has the same characteristics as the tidal current. It is strongest at large water depths away from the coastline and in confined areas, such as straits and tidal inlets.

Current in the Nearshore Zone.

Shore-parallel currents

The longshore current is the dominant current in the nearshore zone. The longshore current is generated by the shore-parallel component of the stresses associated with the breaking process for obliquely incoming waves, the so-called radiation stresses, and by the surplus water which is carried across the breaker-zone towards the coastline. This current has its maximum close to the breaker-line. During storms the longshore current can reach speeds exceeding 2.5 m/s. The longshore current carries sediment along the shoreline, the so-called littoral drift; this mechanism will be discussed further in Section 6.

The longshore current is generally parallel to the coastline and it varies in strength approximately proportional to the square root of the wave height and with sin2b, where b is the wave incidence angle at breaking. As the position of the breaking line constantly shifts due to the irregularity of natural wave fields and since the distance to the breaker-line varies with the wave height, the distribution of the longshore current in the coastal profile will vary accordingly.

Shore-normal currents

Rip currents At certain intervals along the coastline, the longshore current will form a rip current. It is a local current directed away from the shore, bringing the surplus water carried over the bars in the breaking process back into deep water. The rip opening in the bars will often form the lowest section of the coastal profile; a local setback in the shoreline is often seen opposite the rip opening. The rip opening travels slowly downstream.

Fig 5.12

Distribution in longshore current in a coastal profile and rip current pattern. Cross-currents along the shore-normal coastal profile Cross-currents occur especially in the surf-zone. Three contributions balance each other:

- Mass transport, or wave drift, is a phenomenon occurring during wave motion over both sloping and horizontal beds. Water particles near the surface will be transported in the direction of wave propagation when waves travel over an area. This phenomenon is called the mass transport. In the surf-zone the mass transport is directed towards the coast.

- Surface roller drift. When the waves break, water is transported in the surface rollers towards the coast. This is the so-called surface roller drift.

- Undertow. In the surf-zone, the above two contributions are concentrated near the surface. As the net flow is zero, they are compensated for by a return flow in the offshore direction, which is concentrated near the bed. This is the so-called undertow. The undertow is important in the formation of bars.

Two-dimensional currents in the nearshore zone

Along a straight shoreline, the above-mentioned shore-parallel and shore-normal current patterns dominate. The currents discussed in this sub-chapter are two-dimensional in the horizontal plane due to complex bathymetries and structures in the nearshore zone.

Two-dimensional current patterns occur, especially in the following situations:

- When the bathymetry is irregular and very different from the smooth shore-parallel pattern of depth contours characteristic of sandy shorelines, and also when the coastline is very irregular. This can, for example, be at partially rocky coastlines or along coastlines where coral reefs or other hard reefs are present. Irregular depth contours give rise to irregular wave patterns, which again can cause special current phenomena important to the understanding of the coastal morphology. Irregular bathymetry combined with an irregular coastline adds further to the complexity of the wave and current pattern. Reefs provide partial protection against wave action. However, they also generate overtopping of water and compensation currents behind the reef. At low sections of the reef or in gaps in the reef, the surplus water returns to the sea in rip-like jets. This is the pattern for both submerged reefs and emerged reefs with overtopping during storms. Such current systems are of great importance to the morphology behind the reef. Changes in reef structure, natural or man-made, can cause great changes in the morphology.

- In the vicinity of coastal structures, such as groynes, coastal breakwaters and port structures. Such structures influence the current pattern in two principally different ways: by obstructing the shore-parallel current and by setting up secondary circulation currents.

The nature of the obstruction of the shore-parallel currents of course depends on the extension and shape of the coastal structure. If the structure is located within the breaker-zone, the obstruction leads to offshore-directed jet-like currents, which cause loss of beach material. If the structure is a port, the current will follow the upstream breakwater and finally reach the entrance area. The currents in the entrance area will both influence the navigation conditions and cause sedimentation, consequently the design of the entrance is important. It must provide a smooth and predictable current pattern so its impact on navigation is acceptable, sedimentation must be minimised and the bypass of sand must be optimised. The answer is a smooth layout of the main and secondary breakwaters combined with a narrow entrance pointing towards the prevailing waves.

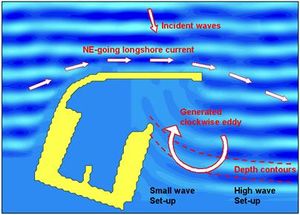

At the leeward side of coastal structures, special current patterns caused by the sheltering effect of the structure in the diffraction area can develop. Sheltered or partly sheltered areas may result in circulation currents along the inner shoreface as well as return currents leading to deep water. The reason for this is that the wave set-up in the sheltered areas is smaller than in the adjacent exposed areas and this generates a gradient in the water-level towards the sheltered areas. These circulation currents in the sheltered areas can be dangerous for swimmers who are using the sheltered area for swimming during rough weather. Another problem is that the sheltered areas will be exposed to sedimentation and such areas must, therefore, be avoided when planning small ports.

Fig 5.13

Lee circulation patterns for a coastal breakwater and a small port. The optimal shape of a small port, avoiding the lee area.

If the structure extends beyond the breaker-zone, the shore-parallel current will be directed along the structure, where the increasing depth will decrease the speed. The current will deposit the sand in a shoal off the breaker-zone upstream of the structure. In the case of a major port, the longshore current will not reach the entrance area. In the lee area of a major coastal structure, the effect of return currents towards the sheltered area will also be pronounced, but the current circulation pattern will be smoother and less dangerous for swimmers. The sheltered areas will act as a sedimentation area adding severely to effects of the lee side erosion outside the sheltered area of such structures. Once again, sheltered areas should be avoided.

- Adjacent to special morphological features such as sand spits, river mouths and tidal inlets. The current patterns and the associated sediment transport at such locations can be very complicated. Only a few general comments will be given in this overview of currents and their impacts.

In tidal inlets and river mouths there are often concentrated currents in the gorge section of the mouth, but seawards of this area the current pattern expands and the current speed decreases. This is also the case landwards of the gorge section in tidal inlets. The gorge section is often deep and narrow, whereas the expanding currents on either side tend to form the ebb and flood shoals respectively. The ebb shoal tends to form a dome-shaped bar on littoral transport shorelines, on which the littoral transport bypasses the mouth/inlet.

Fig 5.14

Ebb and flood shoals at tidal channel, Cay Calker, Belize. This area is mainly exposed to the tidal currents, whereas the wave climate is very mild.